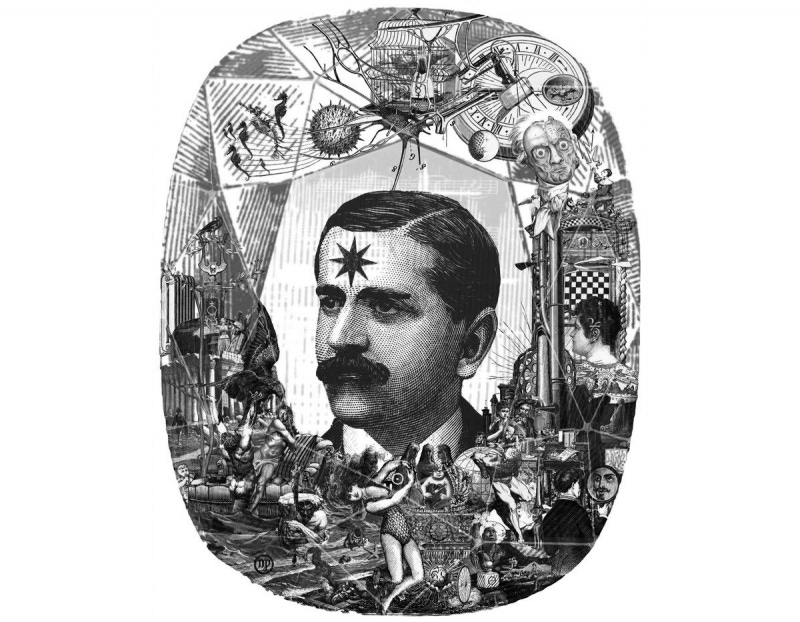

Locus Solaris

War and Theatre #006

To pick up where we left off with Kunstlosigkeit: Raymond Roussel, the most adept machinic writer of the 20th century, introduced a procedural strategy to writing, that some —such as the editors to Foucault’s Language, Madness and Desire: On Literature— explain by appealing not only to Foucault’s strategic relationship to literature as a whole, but to Roussel as grand literary strategist himself; that is, as one of those writers “obsessed with the problem of language, for whom literary construction and the ‘interplay of language’ are directly related. Discovering La Vue by chance in José Corti’s bookstore, Foucault was taken by the “beauty of the style”:

“…even before learning what was behind it —the process, the machines, the mechanisms— and no doubt when I discovered his process and his techniques, the obsessional side of me was seduced a second time by the shock of learning of the disparity between this methodically applied process, which was slightly naive, and the resulting intense poetry.” (Death and the Labyrinth, p.174)

Death and the Labyrinth is Foucault’s only work on literature; the one he wrote “most easily, and with the greatest pleasure,” in two months, after not speaking of Roussel to anyone —including Robbe-Grillet, whose Voyeur had been inspired, as Foucault intuited and eventually confirmed, by La Vue itself— for several years. “Roussel’s enigma,” writes Foucault:

“…is that each element of his language is caught up in an indenumerable series of contingent configurations. A secret much more manifest than but also much more difficult than that suggested by Breton: it does not reside in a ruse of meaning or in the play of unveilings but in a concerted incertitude of morphology, or perhaps in the certitude that a variety of constructions can articulate the same text, authorizing incompatible but mutually possible systems of reading —a rigorous and uncontrollable polyvalence of forms.”1

This interpellation of language is what stands out most to me in the current cohort of AI text-to-image generators, which is why my previous essay reviewed a series of Surrealist techniques —automatism, collage, exquisite corpses and found art— that operate on this frequency, but as if their results were produced from within the dream, rather than without it or, as it were, from the dream’s more complete possibility space, which is larger than it is, and makes allowance for extremes in both experimentation and expression. When I say the case for AI text-to-image generators is predominantly Rousellian, I mean it in a strategic, rather than a technical, way; which is why I am including it within the War and Theatre series.

Foucault’s encounter with Roussel was important to his philosophical development because it provided him with the “extralinguistic” lever that is required to epistemically outmaneuvre —effectively, work around— the fact of discursive immersion.2 The role of the fact and the event are crucially important to the method. Roussel always starts, as Foucault claims, from the “already said,” which he designates “found language”.3 This is how Roussel begins the construction of some of his books, on the basis of very banal and literal prompts: “a sentence found by chance, read in an advertisement, found in a book, or something practical…[taken from songs, read on walls…],” is transformed, juxtaposed or pushed to its outer limits. Roussel does it, furthermore, without using the “generic matrix of the novelistic genre as the principle of development” (DATL, p. 180). What is always present is a transformative factor, that would turn “a common phrase, a book title, or a line of poetry into a series of words with similar sounds” (Ibid., p. 199).

Ashbery equates it to denaturing, in a Mallarméan sense, which is significant because Roussel was a theatre man. If the “already said” is, as Foucault claims, the domain of theatrical verisimilitude, then what Roussel does with his plays is stick a jammer in verisimilitude despite himself, as he genuinely hoped that staging would bring his work to the attention of a broader audience. It accomplished quite the opposite: his first play, an adaptation of Impressions d’Afrique —the one that so impressed Duchamp— was a flop, as was that of Locus Solus. His last two plays, L'Étoile au front and La Poussière de soleils —the first of which resulted in the greatest succès de scandale in French theatre since the opening of Ubu Roi— are, in Ashbery’s words, “theatrical in a curious way”. They are catalogues of anecdotes which, as with the novels, offer little by way of plot, while casting “on the characters who tell them an unearthly glimmer that is like a new kind of characterization.” The mechanic is evocative of that of the 14th century Arabian Nights, or later experiments by the likes of Burroughs and Gysin, where the stories, “cut up […] somehow propel us breathlessly forward”. Leiris, who knew Roussel since childhood, states that “placing the imaginary above all else, he seems to have experienced a much stronger attraction for everything that was theatrical, trompe l’oeil, illusion, than for reality,” a fancy that appears to have percolated into his approach to theatrical production overall.

A contradiction is apparent, but apparent only. “Humankind cannot bear very much reality,” wrote Eliot, and this is the deep realisation of Roussel’s travels and oeuvre, which plumb the depths of the imagination to culminate in, of all actions, an apparent suicide.

Roussel was ultimately a great enforcer in the hard sense Weil describes in her essay on the Illiad: “To define force—it is that x that turns anybody who is subjected to it into a thing”4. Such forcefulness, which inspired the nouveau-roman’s clinical and geometric dissection of banal objects, is a godlike —or machinic— attribute. I would thus like to complement Foucault’s description of “found language” in Roussel with a more emphatic sense of “forced language,” too. Roussel perfected objectification —and the nymphification of many of his characters— to a DesEssentian degree, as have, to some extent, the AI text-to-image generators, which thrive on description and thus objectify all output. They coincide with Leiris’ remark on Roussel’s homegrown transformer model as the rediscovery of “one of the most ancient and widely used patterns of the human mind: the formation of myths starting from words. That is (as if he had decided to illustrate Max Müller’s theory that myths were born out of a sort of ‘disease of language’), transposition of what was at first a simple fact of language into dramatic action (DATL, p. 200, the italics are mine).”

The method to which this analysis applies Roussel called rhymes en faits (rhymes for events, or indeed, for facts), with the fait holding a critical place in his work, as it is the source —the generator— whence the rhyme springs. In this sense, he is first —and peerless— among hyperrealist writers. In this light, the distance he kept from his Surrealist enthusiasts, calling the movement “un peu obscur” despite his pining for acclaim, becomes better understandable. The latitude of operations alters the results.

For one of his short stories he started with a sentence filled with words which offered the potentiality for multiple meanings. By changing one letter he created a second sentence with an almost completely different meaning. These two sentences formed the beginning and ending of his story. From there the puzzle was getting from one to the other.5

How I Wrote Certain of My Books describes a hand-made, ready-made transformer language model. Roussel is not a “primitive” in any regard, whilst being the most primitive High Modern of them all. We are only beginning to glimpse how far ahead of just what curve he was.

Michel Foucault. Death and the Labyrinth. The World of Raymond Roussel (trans. Charles Ruas). London/New York: Continuum, 2004 [1963].

—. Language, Madness and Desire: On Literature (La grande étrangère: À propos de littérature, trans. by Robert Bononno). Minneapolis/London: University of Minnesota Press, 2015 [2013].

Various authors. Locus Solus. Impresiones de Raymond Roussel. Exhibition catalogue for Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofía and Museu de Arte Contemporânea de Serralves, with collaboration from the Bibliothèque nationale de France. Madrid, 2011.

Simone Weil. “The Illiad, or the Poem of Force.” In War and the Illiad. New York: New York Review of Books, 1989 [1945].

Michel Foucault. Language, Madness and Desire: On Literature (La grande étrangère: À propos de littérature, trans. by Robert Bononno). Minneapolis/London: University of Minnesota Press, 2015 [2013], p. xi.

An intuition shared by Cocteau, who said he had “constructed defenses” to defend himself against Roussel’s “genius in its pure state” by being able to “look at him from the outside” (DATL, p. 189). Ashbery adds that “the nature of his work is such that it must be looked at ‘from the outside’ or not at all” (Ibid, p. 190).

And Foucault and Ruas expound at length on whether the process would even be discernible if How I Wrote Certain of My Books did not exist. This is the golden key to the Rousellian game: it comes with a statement of brinkmanslike intent. Foucault speaks of how awareness of this process adds “tension” to the beauty of the work, a matter we have already parsed in our essay on difficult beauty.

Simone Weil. “The Illiad, or the Poem of Force.” In War and the Illiad. New York: New York Review of Books, 1989 [1945], p. 3.

Again, see https://madinkbeard.com/archives/roussels-method for a more detailed breakdown of the procedure.

Ain't it just like the night to steal your soul and vaporize it in nanotechnics, Louise tempting you to deny a handful of rain?