In Canto LXXIV, Ezra Pound, c[h]a[r]ged because he could not change, wrote1:

Les hommes ont je ne sais quelle peur étrange,

said Monsieur Whoosis, de la beauté

La beauté, ‘Beauty is difficult, Yeats’ said Aubrey Beardsley

when Yeats asked why he drew horrors

or at least not Burne-Jones

and Beardsley knew he was dying and had to

make his hits quickly

hence no more B-J in his product.

So very difficult, Yeats, beauty very difficult.

‘I am the torch’ wrote Arthur ‘she saith’.

These ideas are not original or rather, they can only be original.2

In his Three Lessons on Æsthetics, Bosanquet distinguishes between “facile or easy and simple victorious beauty” —the sort you ‘like’ to see— and “difficult beauty and difficult triumphant beauty” (the one you may not ‘like’ or won’t, without some effort).3

Within the aesthetically excellent, he qualifies the latter as being distinguished by at least one of three characteristics (though not limited to them, either): “intricacy, tension” and —the most surprising one— “width”.

Intricacy is a surfeit, too much of a good thing; it points to the constitutional capacity that certain aesthetes have to digest filigree in ways analogous to how ruminants go about the business of absorbing cellulose. Intricacy is not for the faint of imagination, let alone for those with maybe less than a four-chambered one. It is the foie gras of the aesthetic spectrum —ungood for the goose, if good for the grandeur— requiring margins of subjective taste and objective tolerance for gavage that may be physiologically impossible, unbearable, for almost anyone of normal build.

As must always be the case with us, tension introduces the baroque element. It will seem the most familiar to readers already acquainted with the aesthetic dimensions of the unhomely and the uncanny; being suggestive of discomfort and unease, of the “Borromean knot of harmonious discord” with which Christine Buci-Gluckman describes the hyperstylised perspective of the baroque as being reduced —and exploded— into “seeing and living only to see”.4 The violence in this mutually assured surveillance is however, overt: a “moment of suspense, what the Greeks termed αρπαζειν, to captivate, to capture, to take by force, to seize in the sense that one can be seized and seize, let oneself be taken and freed.” The connotations of possession, rapture, ἐνθουσιασμός —the being taken and possibly taken apart by a higher power— are explicit.5 Tension in this sense must perforce be understood within the sphere of “weapons and war”, that is —and it is why I cite Gracián— as baroque theatre.6

In our particular reading, then, width —described by Bosanquet as “a sort of dissolution of the conventional world”, can be derived from the fulfillment, dilation and/or culmination of this tension: it is, in other words, our own Covidian hyperbaroque. Jacquette describes ‘width’ as the preserve of “apocalyptic art and the art of havoc, great comic farce, and theatre and film noir.” (The long and short of this is obviously opera, the great un-sung genre of our time, on which I will have more to say next week via Strauss’ and von Hofmannstahl’s Ariadne auf Naxos, an outstanding and urgent example of ‘width’ for our time, as it incorporates each element in Jacquette’s breakdown to an extraordinary degree of intensity and accomplishment).

Apocalyptic art, as we have elsewhere discussed, is art that reveals; art that makes the theatre mechanics as seamless to the act —and as central to the epistemology— of theatre itself, without detriment to our suspension of dis/belief. It is the perpetual motion picture of hyperreality. The only art that’s left us is complete, immersive theatre: Sleep No More, Forever, with as many Inter-missions/ Side-quests as you heart can handle. (‘Intricacy’, as we were saying: “I am the torch”, and all that).

But to return to Pound, as he was —no less than Bosanquet himself— the coiner of ‘difficult beauty’, and how we first got ourselves into this particular conundrum.

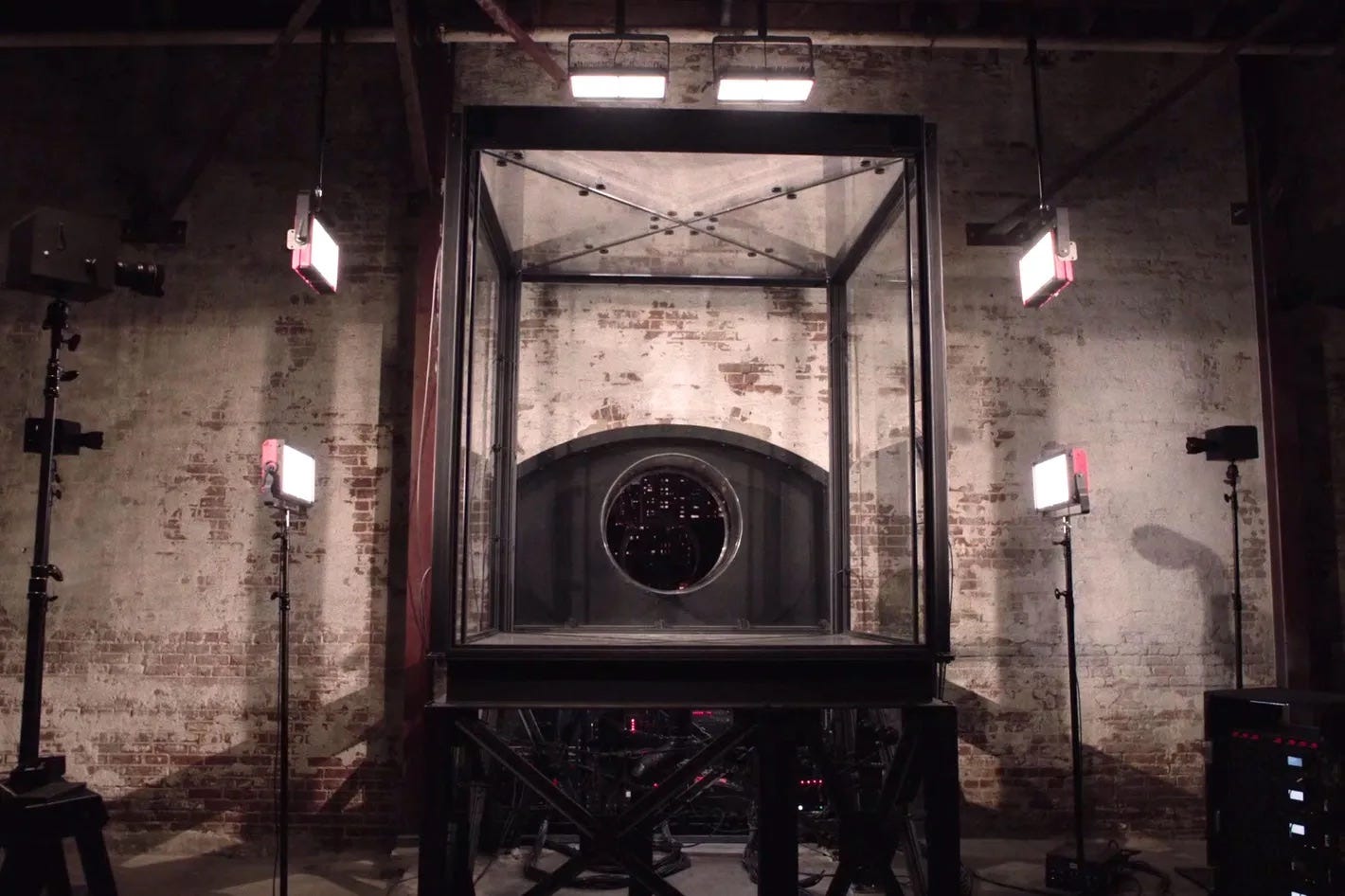

Here is a case in width; to wit, one spanning three weeks by 2m x 2m, the term and total area of Pound’s rapture-space —his ἐνθουσιασμός— by the United States Army Disciplinary Training Center in Metato, under charge of treason.7

There is one example that echoes such a space, and it is the overture to the Gesamtkunstwerk that is our generation’s undisputed masterpiece of width:

Ezra Pound, The Cantos (London, 1975); Canto LXXIV (Pisan Cantos, 1948), p. 444.

There is a sense in which the last stanza of the Canto serves as an obituary for Symonds, whose "Modern Beauty” reads so closely as a burn to Yeats’ “No Second Troy”. To his “Was there no second Troy to burn?” Symonds responds: “Still am I / The torch, but where’s the moth that still dares die? It is difficult beauty —” that has been abandoned. Yeats’ diminished Maud Gonne’s dangerousness, her triumphantly difficult beauty; Symonds implicitly paints Yeats as a pious suitor who lacks himself the “courage equal to desire” he denounces in his Gonne’s acolytes.

Dale Jacquette. “Bosanquette’s Concept of Difficult Beauty.” The Journal of Aesthetics and Art Criticism. vol. 43, No. 1 (Autumn, 1984), pp. 79-87. Oxford: Wiley, The American Society for Aesthetics.

Christine Buci-Gluckman. The Madness of Vision. On Baroque Aesthetics (trans. by Dorothy Z. Baker). Athens: Ohio University Press, 2013.

My next piece will go considerably deeper into ἐνθουσιασμός in the context of what Calasso called nympholeptic possession.

The saying “there is no excellent beauty without some strangeness in the proportion” is ascribed to Poe but comes in fact from Francis Bacon. It is not thus a romantic perspective on beauty —it’s an Early Modern and baroque one. (Poe did repurpose it, pivoting the strangeness of this beauty from the ‘excellent’ to the ‘exquisite’).

https://evokeagents.blogspot.com/2020/12/ezra-pound-scrittore-antisistema.html

Footnote 6 is most excellent! 👏👊