"I felt that as a painter it was much better to be influenced by a writer than by another painter." —Marcel Duchamp, upon spectating Raymond Roussel's Impressions d'Afrique in 1912

A first observation on DALL-E 2 and its ilk: like any instrument, it benefits substantially from practice; with false notes and bad takes galore, from the start. The amount of refuse it produces is considerable and redolent. As is ever the case, a mutual entrainment is called for betwixt man-and-machine. And as with any instrument, one will —at least relatively— get what one puts into it, practically speaking, with experimentation leading to increased proficiency and refinement.

—Your database is so large! —The better to see you.

These text-to-image generators do not pose a threat to art —no technology does. What they constitute is another element in art’s becoming. Technology —and lets recall τέχνη is craft, so also ars— is not neutral, though it may well be a symbiotic and mimetic adaptation, wherein we are basically provided with the affordances that we can handle. The grasp is both a primal reflex and a lifetime’s education. Artists should consider AI-art generators as what they are —new media, with AI as potential new actor in an interlocutionary capacity. This being a competitive, collaborative or comparative relationship is —again— up to the artist, and I can conceive of fruitful work being borne from each of these approaches.

That there is a rhetorical and hence a performative dimension to τέχνη is why I appeal to the development of an interlocutionary relationship between artists and generators. The challenge to artists is phronetic here: an appeal to their better judgment (which may translate into ‘taste’ as tacit knowledge).

Two more maxims, if you will have them. The first: great artists will never be out of demand (if anything, the demand for —and exigency for— great artistry may increase: the human touch providing its own store of value). The machine does not and cannot do what you do. Second: great art can be produced by any means, because it is necessary. It is, in that sense, the most accessible Machiavellism, which raises the point of artistic intent. On this particular count, I think of it as I do about sexual consent: if purpose must always be made explicit, it inhibits the means of seduction, which debilitates transgression (hard limits force hard trespasses; nebulous boundaries can be trickier, as they are coded in a way that is not shared: the transgression loses force in reaching the escape velocity that makes it legible as such).

So, to this effect, I’d like to borrow Hoffmann’s term, Kunstlosigkeit, which can be translated as “non-art” or “art loss”, in the sense of lacking artifice. This is, I think, where the heart of concern surrounding these text-to-image AI programs lies: in the distance, perhaps, between play and deep play. The former is innocent, the latter is knowing. (And we will be revisiting the implications of brinksmanship and deep play —an enduring concern of this substack, and the other one— quite soon).

In the meantime, to do so, I’d like to scroll back a century and repair on some Surrealist tropes. I do not intend to give you the answers —or not yet— but to insinuate some possibilities for serious explorers. Consider this an ongoing conversation.

Automatism

Though sometimes downplayed by the Surrealists themselves —as Ángel Pariente’s exhaustive repertoire of Surrealist ideas discloses— automatism was a cornerstone of the movement, even if it was not exclusive to it. In a way, it is the most antiquarian of all Surrealist practices, because it so closely resembles channeling, and clearly draws from it. It is also a kenotic practice, in that it stems from a voiding of the artist’s ego —which can be attained through numerous means— to record what lies ‘below’, in the purported unconscious, or ‘above’, be it as idic or superegoic epiphenomena.1

The generators obviously work from surfaces, but the implications are deeper: “think”, writes technologist Anton Troynikov, “of the homogenisation of taste through the algorithmic feed, to the point we create culture to feed the algorithm [though] the algorithm is distinctly not human.” (Let this be the placeholder for our corollary on the Rousselian method.)

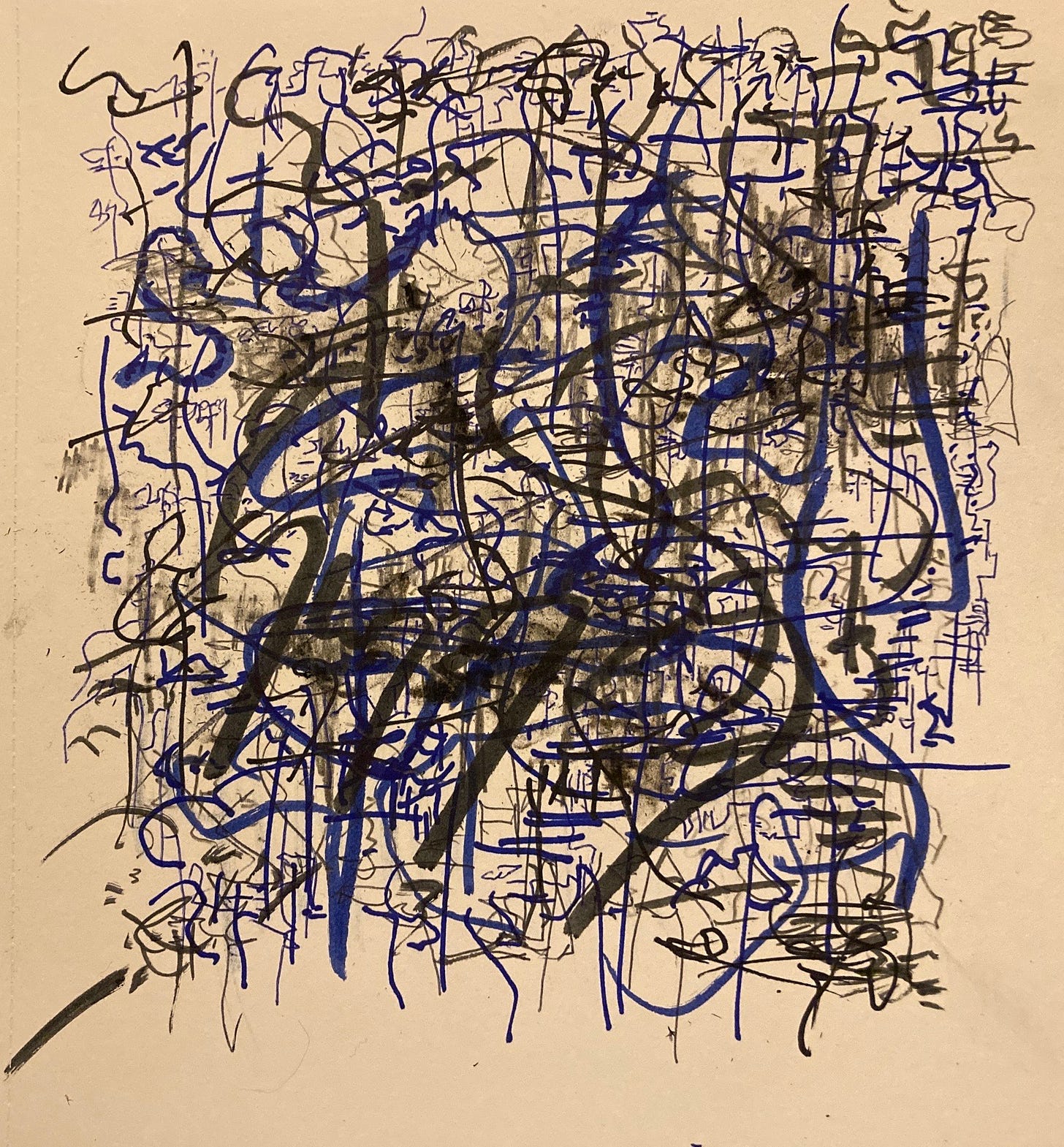

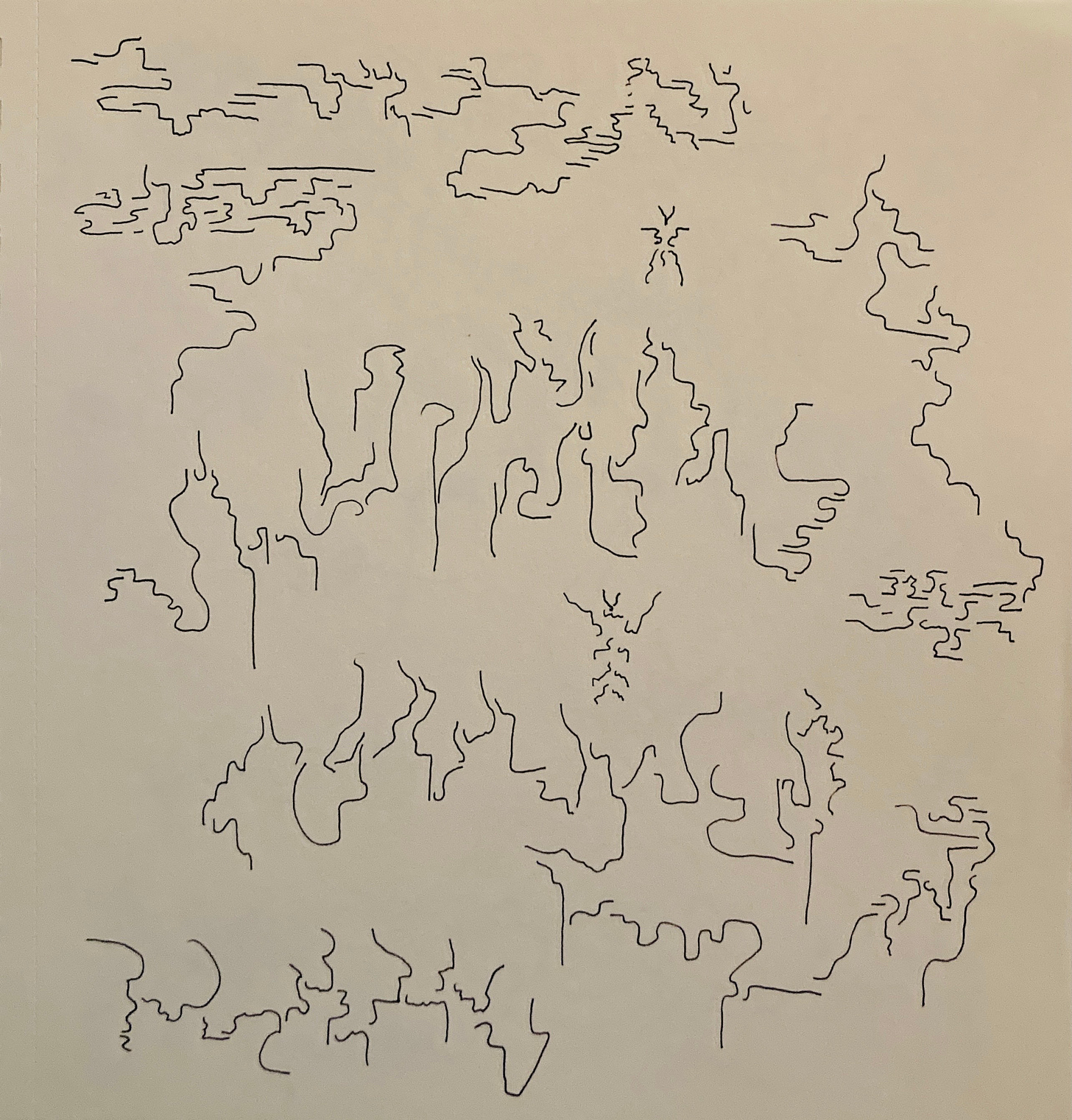

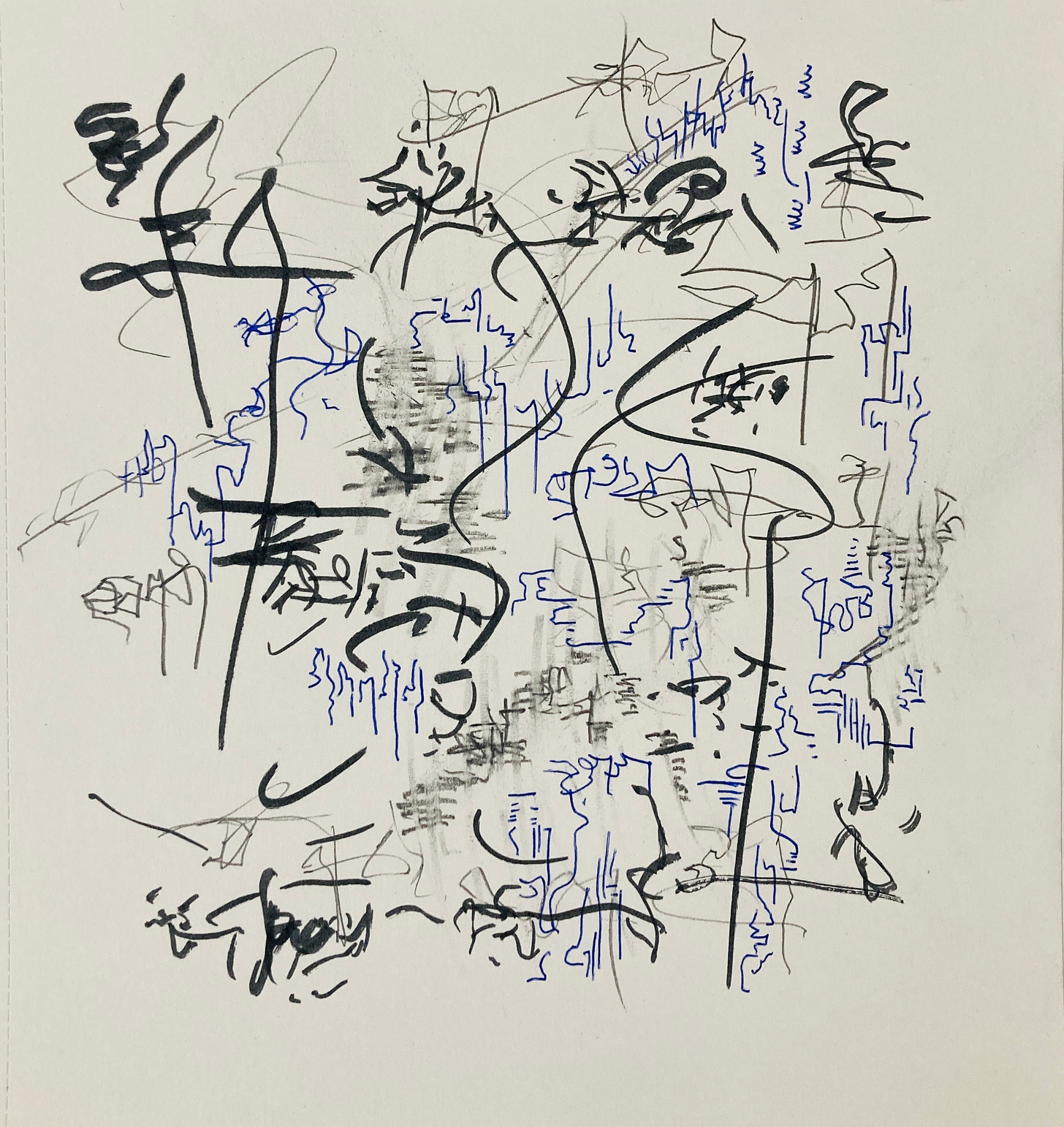

For the purposes of this piece, I exchanged impressions with two contemporary automatists, the philosopher Arlyn Culwick, whose interesting work —Bollocks Portraits— you can see here, and the poet Garett Strickland, of whose work some examples are here.

Culwick describes his practice as prankish and insightful, whereas Strickland offered me this stunning text, which I will reproduce in full:

“My visual art practice began quite simply in deciding to make marks. The further I pushed into performing something of my own trace, the more this ritual of manifesting presence thru the creation of artifacts began to dovetail with my lifelong interest in writing and language, occupying a space between alien script and the depiction of forces in motion, the pursuit of an evasive universal sign in the perpetual flux of all weathers. In actualizing a body of work whose ephemerality is built into what’s ever being created, a parallel continuity to that of the artist’s own step is developed, even or especially as it exceeds comprehension. A threshold is established, wherein we are always a little ahead of and meeting ourselves in the gesture of a line extending in every direction at once, harvesting from what does not or will no longer exist, a signal that remains unchanged thru all its variations.”

Collage

While also not an exclusively Surrealist technique, its Surrealist master was without a question Max Ernst, who naturally had to extend the practice by means such as frottage. An unspoken value of collage, presented sometimes in terms of mere contrast or juxtaposition, is hard, physical, even sexual friction. The Surrealist dictum: “a chance meeting on a dissecting table of a sewing machine and an umbrella” is an erotic charter on collage-making. The element of chance is a diversion: what matters is the encounter —the superimposition— of umbrella and sowing machine, which must be intended and mediated as such by the artist. He facilitates our seeing a connection where there wasn’t one beyond adjacency before. This is, for example, artistic intent. It is not in the final form —even when it is— but in the original formation.

In his soon-to-be-published book, Figured Stones, Paul Prudence refers to Ernst’s work as follows:

“Under his self-invoked spell of form-insinuation he reworked the chaotic textures into entire worlds so that discord was exchanged for order and an evolution granted with a kind of aesthetic natural selection.”

If we settle on Ernst, the collagist, as being at the intersection of the so-called “sex appeal of the inorganic” + “aesthetic natural selection”, the result is: one of the 20th century’s great artistic human generator-predecessors.

Because collage requires a searchingness as well —a finding and timing of the right pieces, like intuitive clockwork— it is more propulsive than, say, found art —where it is often the object that compels the artist.2 This, to a certain extent, resonates with incentivising the inscription of ‘smart’ prompts into the text-to-image AI, for maximum effect. While the ‘detailing’ in the input does not necessarily translate into an equally detailed output (behold my peacock above, borne of four words, and let’s recall my Black Box Theatre Theory), serious experiments in DALLE-E and Midjourney by Fernando Borretti present one of the most effective users of AI-art generation I have seen to date.

I do not question his intent, nor do I ask him about it. To me it is very clear that Borretti is approaching this with gusto, as a programmer with a special savvy for the ars combinatoria. For one, he tends to cite, rather than write, the desired form by doing so not only in adherence to academic conventions, but —most notably— by introducing elements of the eventual artwork’s lifecycle, such as it being “auctioned at Christie’s”. (Nor let’s dismiss citation as a recall mechanism). There is a methodical and narrative design to Borreti’s procedure, and his approach is completely cerebral, Borgesian or Bioyesque. I would do him a disservice to post one of his images when the magnitude and seriousness of his investigation require that you follow him @zetalyrae. His is a durational inquiry, which I think is and will continue enlivening the conversation in substantial ways.

Exquisite Corpse

The Surrealist pastime of exquisite corpses, an early parlor game revived by André Breton in the 1920s, thrives on segmentation, subjectivity and variety. Though they arise from a series of restrictions, the forms exquisite corpses produce are not restrained. They are additive, but not integral; sequential, but disorganized and non-hierarchical; partial, because cut into pieces. The desired effect is that of a jarring, horizontal juxtaposition.

This horizontality, which I have also heard described as “acousticity”, is the increasingly pale watermark of AI-art. The results of one throw at DALL-E 2 can be irretrievably grotesque, and the grotesque is important to us for two reasons: as per Ruskin, it can be revealing, and —it presumes of a niche. I will write more on this as well.

Found Art

Though the concept is ascribed to Duchamp, the notion of found art first struck me in Valéry’s Sea Shells. To me, it goes beyond the “sex appeal of the inorganic” —the defining limitation of the celibate machine— to represent the peak intentionality of the artist as artificer or unnatural selector. Valéry writes:

“…that it would be a waste of time to think in our own way and no other about an object that suddenly arrests us and calls for an answer… I look for the first time at this thing that I have found. I note what I have said about its form, and I am perplexed. Then I ask myself the question: Who made this?”

This sense of mystery and marvel, this tracking of human τέχνη vis-à-vis the ποίησις of nature, seems inherent to finding art outside conventional frames. An object isn’t chosen for lack of virtue, even if it is its modesty. There is something about it that elicits the artist’s response, and which may account for an aspect of intent that is discussed less often than ‘will’: predisposition.

To find art, one must want to find art.

Corollary: The Rousselian Procedure

Not technically Surrealistic, nor even a technique, but one of the movement’s great undeclared strategies, taken to its limit by its unwitting godfather Raymond Roussel, whose procedure, as explained in Comment j’ecrit certains de mes livres (1935), is polysemic and homophonic. (The generators rhyme, remember this.)

For one of his short stories he started with a sentence filled with words which offered the potentiality for multiple meanings. By changing one letter he created a second sentence with an almost completely different meaning. These two sentences formed the beginning and ending of his story. From there the puzzle was getting from one to the other.3

Roussel’s writing is inhuman; both an algorithm and a blockchain.

Together with Duchamp, Jarry, Artaud, Burroughs and Wyndham Lewis, I consider Roussel one of a six-fingered handful of terminal past century artists whom it is essential for us to recover to understand the operations of our hyperbaroque and its doubles.

It should go without saying: Roussel was, of course, a theatre man.

He deserves his own essay, and we will give it to him.

With gratitude to Logan Berry, Fernando Borretti, Arlyn Culwick, Julien Nguyen, Garett Strickland, Paul Prudence, Alonso Toledo, and Anton Troynikov —all of whom made this exploration and the conclusions therein plausible through our recent discussions on the state of the art.

Mónica x DALL-E: “Peacock, Belle Époque, Klee”.

André Breton. Manifiestos del Surrealismo (Manifestes du surréalisme, trans. by Andrés Bosch). Madrid: Visor, 2002 [1924-1953].

Frances S. Connelly. Lo grotesco en el arte y la cultura occidentales. La imagen en juego (The Grotesque in Western Art and Culture. The Image at Play, trans. by Amaya Bozal). Madrid: La Balsa de la Medusa, 2015.

Werner Hoffmann. Los fundamentos del arte moderno. Una introducción a sus formas simbólicas (Grundlagen der Modernen Kunst, trans. by Agustín Delgado y José Antonio Alemany). Ediciones Península: Barcelona, 1992 [1987].

Ángel Pariente. Repertorio de ideas del Surrealismo (1919-1970). Logroño: Pepitas de Calabaza, 2014.

Mario Perniola. La estética del siglo veinte (L’estetica del Novecento, trans. by Francisco Campillo. Madrid: La Balsa de la Medusa, 2001 [1997].

Paul Prudence. Figured Stones. Scotland: Corbel Stone Press, 2022.

Paul Valéry. Sea Shells (L’homme et la coquille, trans. by Ralph Manheim). Boston: Beacon Press, 1998 [1937].

Various authors. Locus Solus. Impresiones de Raymond Roussel. Exhibition catalogue for Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofía and Museu de Arte Contemporânea de Serralves, with collaboration from the Bibliothèque nationale de France. Madrid, 2011.

Culwick dixit: “the hardest time I've had making even these silly pictures was in 2019, when I ended up in Sicily on an artist residency. Suddenly I was an ‘artist’. Argh. Granted, the process is unusually sensitive to that sort of thing.”

The ready-made, for instance is found art + sculptural collage.

See https://madinkbeard.com/archives/roussels-method