I want to grasp things with the mind the way the penis is grasped by the vagina. —Marcel Duchamp Warfare and worldly power could thus conceivably find justification and sacralization in the Tantras. —Imma Ramos, Tantra: Enlightenment to Revolution, p. 36

In search of a scenario that can contemplate mimetic violence and kenotic love at once —in seeking out a more permissive template that promotes the “grinding of the models” found in imitation and self-voiding1— I have hinted at the possible use for a tantric revival. In a recent tweet-thread, Nina Power questions how to “mass break people out of scrupulosity. A third summer of love is overdue,” she writes. “But perhaps a mass Dionysian ego-dissolution will not happen in the same way again.”2

It can and will not. Given current transvaluations, a third summer of love would be improbable, as love has been commoditised, steered into allyships and tamed into triumphal parades of conformist acceptance. The orgiastic is declawed, and the willingness to “retvrn” amongst our youngest —whom should also be our most transgressive— belies a deep need for certainties and safeties that cannot be had, but which concentrate enormous wellsprings of desire.

Let’s start by saying that tantra shouldn’t be reduced to sex —“emblematic” as it may be to it— but that its practice is expressed and expanded through it. In other words, it treats “sexuality and spirituality not as identical, but as having the same origin,”3 which makes it about reaching power and enlightenment through unorthodox means. These means are fundamentally aesthetics and eroticism4, where creative energy is identified with the erotic impulse, or more precisely, with “the union of (male) consciousness activated by (female) creative energy.”5

In her intriguing evidentiary analysis of tantric influences in Duchamp6, Jacquelynn Bass writes: “One of the things that distinguish Asian from modern Western spirituality is an understanding of eros as transformative energy capable of unveiling absolute reality —in Duchampian terms, stripping reality bare.”7 She quotes his New York gallerists, the Janises, to explain how Duchamp’s “concept of the art of life” had two aspects: “first, identification of the creative impulse with the erotic impulse (‘procreation’) and, second, a resulting vivid awareness of an absolute reality hidden within everyday reality”.8 These are further tied into “inspiration”, with its onus on breathing, which Duchamp liked to cite as his “true art form, and infusion by a power that is at once transcendent and immanent.”9

It may be helpful to add that ambiguity around the interpretation of the Tantras is:

“partly resolved, or at least explained, by the distinction between [its] ‘left-hand path’ (vamachara), which interprets the instructions of Tantric texts literally, and [its] ‘right-hand path’ (dakshinachara), which interprets them symbolically, through visualization techniques and by using substitutes (such as milk and flowers) for taboo substances or acts. This ‘softening’ or ‘sanitizing’ of Tantra made the movement more acceptable among popular and even monastic, celibate audiences, ensuring its mainstream dissemination while simultaneously respecting the greater power promised by the ‘left-hand path’.”10

This process has been successfully advanced and maintained since the 6th century for two reasons. First, it proliferated because tantra is neither monolithic nor dogmatic. Second, out of all religious traditions, it is the one best aligned with a taste for brinkmanship or edging, that helps push or even cut through discourse like a cuticle is pushed, or cut out, by a manicurist.

Brinkmanship, which I first brought up here, is a “necessary” art of war —what former US Secretary of State John Foster Dulles designated as “[t]he ability to get to the verge without getting into the war”.11 It is certainly an element in the theatrical epistemology proposed by Covidian Æsthetics inasmuch as it involves —in the words of Thomas Schelling, the definitive scholar on the subject— “manipulating the shared risk of war”.12 Extend this to our “culture wars” and you may see what I am aiming for: the need for credible threats against prevalent righteousness.

This is why I question whether the ‘softening’ suggested by Ramos that was so conducive to earlier tantric penetration is what is needed today. My impression is this new tantric wave would call for intensification in a way that counters all forms of traditional LARPing with deep play, a term first coined by Bentham and then recovered by Clifford Geertz in his “Notes on the Balinese Cockfight.” A classic of anthropology, Geertz’s essay uses the Balinese cockfight to illustrate the utilitarian concept of games with stakes so high no rational agent would engage in them —but for the fact that we are not, alas, rational agents. Supplantation, projection, inversion; symbolic economies, rulemaking and breaking —how to get away with what, and when not to— can all be found in what’s, at heart, a striking sort of deep-play-book.

Even as I have previously defended the lack of need for a sacred frame or circumscription —a hierophany can manifest in unsuspected places that have not been designated as sacred before— I also find a special use for ritually-bounded sacredness as a testing ground for the transfiguration of values in a contained manner. As we simultaneously undergo a major axiological shift in a daily, global and immersive, uncontrolled way, the sacred could be set up as a control system —and so acquire experimental value, in addition to its patent experiential worth. This could in fact be claimed to be a fundamental purpose of sacrality —which is beyond ‘good’ and ‘evil’— as a social technology.

And if social tech is what the sacred is, it's also why it can be re-produced, despite its uniqueness. In referring to the metaverse, Covidian Æsthetics group chat member and VR expert Andy Hartzell refers to it as: “an arena for performance, for trying on masks…ultimately it’s about ritual: representation, not duplication.”13 The more things change! In the words of David Gordon White: "In the Tantric context what has perhaps been essential is not keeping a secret itself, but rather maintaining a cult of secrecy, […] maintaining a secret identity in a society where keeping secrets is a near impossibility. [...] In other words, dissimulation or role-playing by the Tantric practitioners [...] was [...] a means by which householders could maintain an acceptable public persona", or, as Bass adds, "to create an aura of mystery," which she compares to Buddhist esoteric art that —in the words of Cynthea Bogel— "diverts attention from their magical efficacy at the same time it intensifies it."14

We live in a world not dissimilar to that described by Gordon White, where maintaining an acceptable public persona is no less crucial a skill than dissimulation and roleplaying, and preserving an aura of mystery becomes essential to the sustenance of both consistency and charm. What’s critical is doing so in a spirit of deep play, that transcends the LARP by protecting —and promoting, and provoking—what LARP lacks: the esoteric —and the implied erotic— lived as the “vivid awareness of an absolute reality hidden within everyday reality.” To cite Éluard, there is another world —and it’s in this one.

Add to this that the overlap between simulation and ritual is demonstrably effective. Transubstantiation is an interesting example of the literal and the symbolic sharing of a same space: the wafer is the body of Christ, the wine is His blood. But it is being offered not literal flesh and blood, but their substitutes, that makes the experience recursively palatable to the masses. Theophagy is not for the faint of heart.

“Tantra was never a monolithic religion, but rather an adaptable sacred tradition that was incorporated and appropriated by other belief systems, beginning with Hinduism and Buddhism […] In the modern age, [it] has become a blank canvas onto which people have projected certain ideals. […] It constantly transformed in response to its social, political and cultural environments [but] its one recurring thread (to take its literal meaning, ‘to weave’, as a central metaphor) has been its role as a fundamentally countercultural movement.”15

To date, we lack an organising principle around which to articulate a counterculture that is not inherently reactionary or that harbours genuine revolutionary promise. I do not propose a return to tantrism —since no return is possible, and as it never left— but a reassessment of its possibilities and principles, adapted to our current needs. It may —and likely should— look different than expected, as Duchamp’s own art looked different than expected, by virtue of providing probably the most adaptable and flexible conceptions of sacrality and esotericism available to anyone, at any time. The most credible threat that one can cast against the culture war is to proceed be[d]side it.

What I am proposing cannot be adopted at scale in the West today. It cannot accomplish what the hippy movement, for example, did in its time. As we are not prepared for revolution, it is not the stuff for politicians (Marianne Williamson is not a viable candidate, though she is a loved one). What I am proposing must be undertaken by artists and technologists who want to steer culture out of the current headlock that it’s in, moving it inward and forward. It would be an elitist movement with populist implications. As technology and art become increasingly indisociable, we should strive for the procreative “union of (male) consciousness activated by (female) creative energy” in and through them.

And —what do you know— it is happening again.

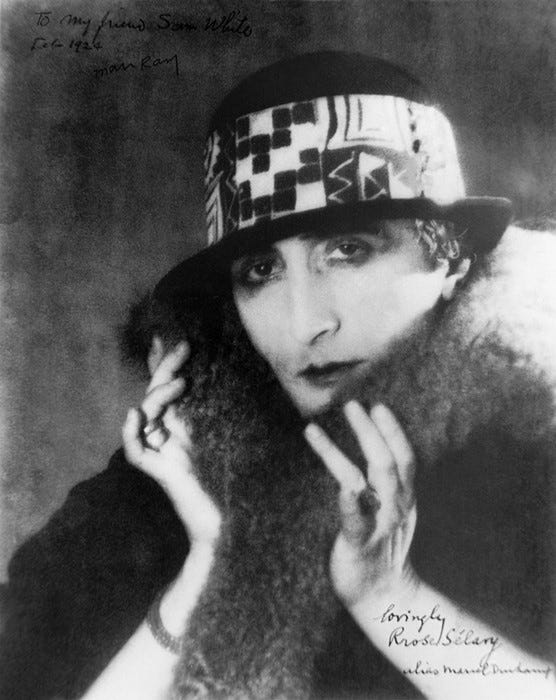

Man Ray. Marcel Duchamp as Rrose Sélavy. c. 1920-1921. Gelatin silver print. 21.6 x 17.3 cm. Philadelphia Museum of Art.

Jacquelynn Baas. Marcel Duchamp and the Art of Life. Cambridge, MA/ London: The MIT Press, 2019.

Clifford Geertz. “Deep Play: Notes on the Balinese Cockfight.” The Interpretation of Cultures. New York: Basic Books, 1973.

Imma Ramos. Tantra: Enlightenment to Revolution. London: Thames and Hudson / The British Museum, 2020.

Thomas C. Schelling. Arms and Influence. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1966.

James Shepley. "How Dulles Averted War." Life Magazine. 16 Jan 1956, pp. 70ff.

Arlyn Culwick, Covidian Æsthetics group chat, date N/A.

Nina Power, Twitter, August 19.

Jacquelynn Bass. Marcel Duchamp and the Art of Life. Cambridge, MA/ London: The MIT Press, 2019, p. 18.

Jacquelynn Bass, ibid, p. 16. “In addition to physical practices, sexual rituals were interpreted by educated practitioners as psychosomatic exercises intended to dissolve ego and remove the veil of otherness from manifest reality, revealing the inherently aesthetic nature of lived experience. Duchamp’s understanding of the aesthetic as disinterested delight in the interconnection of the senses and the mind was presaged by India’s great aesthetician, the tenth/eleventh century philosopher and Kaula practitioner Abhinavagupta.”

Bass, ibid, p. 5.

Bass, ibid, pp. 18-20. There were only two times where Duchamp alluded explicitly —if somewhat glancingly— to tantrism.

The first was in 1959’s “Succint Lexicon of Eroticism”, for his joint catalogue with Breton for L’Exposition inteRnatiOnale du Surréalisme, which reads: “TANTRISM. Body of cosmological and mystical doctrines of Hindu origin. In tantric yoga, awareness of sexual energy (Shakti) as a modality of cosmic energy allowed ascetic reintegration of the primordial Unity.” [“The mention of Shakti and emphasis on ascetic (a homophone of aesthetic) reintegration suggests that Duchamp’s and Breton’s referent was non-dual tantric Shaivism”, writes Bass].

The second and more telling episode was in an interview with Lanier Graham, near the end of his life, where they discussed the Androgyne —a universal symbol “above [religion or] philosophy”— that includes an alchemical perspective which Duchamp states “we may also call Tantric (as Brancusi would say), or (as you like to say) Perennial.” He deftly takes credit for neither interpretation.

Bass, ibid, 4.

Bass, ibid, p. 4.

Bass, ibid, p. 7.

Imma Ramos. Tantra: Enlightenment to Revolution. London: Thames and Hudson / The British Museum, 2020. Note these ‘paths’ reappear in Durkheim and in his assiduous reader, Bataille, as well as in Crowley.

Ramos also observes how “how fluid the boundaries were between left-hand and right-hand forms of Tantra itself. Indeed, there is no single, monolithic Tantra; instead there are many shades of it, and its adaptability has always been the key to its success. The right-hand path made Tantric traditions accessible to a wider, more mainstream audience beyond the cremation-ground-dwelling ascetics. However, all acknowledged —whether with awe or horror— the power of the left-hand Tantrikas who, as mentioned, were often referred to as literal heroes in Tantric texts due to the dangers involved in their pursuit of a fast-track to enlightenment as well as supernatural abilities and worldly domination” (p. 35-36).

James Shepley. "How Dulles Averted War." Life Magazine. 16 Jan 1956, pp. 70ff.

Thomas C. Schelling. Arms and Influence. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1966.

Andrew Hartzell, Covidian Æsthetics group chat, date N/A.

Bass, ibid, p. 22. This perspective is none too different than that shared by Tomoé Hill in the first part of her guest column “Breath and Belief”, here.

Ramos, ibidem, p. 22.

What’s wild to me is how loving the sacred & aesthetic seems to be incompatible with utopian ideology. Given that it does appear to be a choice, I’d rather be happy than good. Also, this piece was sexier than anything on Pornhub.

YES!. Ironic that there were so many "orgasm-worthy" lines in this! heh