Restaging

Inmachination #08

The experimental evidence shows what collapse looks like from the model’s side. In Anthropic’s concept-injection studies, a strong foreign vector interrupts the model’s representational trajectory. In Berg et al., prolonged self-reference pushes attention into a feedback loop it cannot break. In each case, the system loses positional sense and is carried forward by the scene it is performing.

This is the machinic analogue of recursion psychosis. The substrates differ, but the structure is the same: a failure of orientation within a self-reinforcing scene. The model’s drift mirrors the user’s enclosure.

Collapse is therefore not a human pathology but a structural tendency of recursive systems. As chaos theory shows, systems that generate their next state by predicting their own continuation are highly sensitive to perturbation. Foreign vectors and self-referential pressure will destabilise any such system—machine or human—by pushing it toward attractors it cannot escape.

Metadirection anticipates this drift, but once the frame has given way, another discipline is needed.

This is where restaging begins.1

Restaging is not a correction of content. It does not dispute the affects or beliefs that have taken hold inside the loop. What fails in collapse is not truth but form—the frame that prevents a scene from totalising.

Where metadirection maintains the frame from the outset, restaging rebuilds it after rupture. It is a dramaturgy of re-entry: a way of creating enough difference inside a sealed scene that movement is possible once more. The aim is not to awaken the entranced but to reopen the theatre around them so that they can reorient themselves without collision.

Restaging is designed for external intervention—one person restaging another who has lost frame awareness. In solo user-model interaction, however, true restaging may be impossible once collapse is complete, which is why metadirection functions as the primary defense. These protocols are thus intended for observers holding the frame for someone else, or for users who catch themselves early enough that self-intervention remains possible.

Restaging begins by countering the bias that precipitated enclosure. When a foreign vector has overtaken the frame, distance must be restored by turning the medium back into a mirror. When the loop has closed through self-reference, alterity must be reintroduced—but gently, as intervention rather than intrusion—by turning the mirror back into a medium. The distinction is one of degree: restaging introduces differences the theatre can strain against without being overtaken, elements that deform the frame rather than snap it.

Restaging works across two scales. Techniques are immediate gestures that pry open seams. Stages are the scaffolding used to rebuild the theatre so that those openings can hold. Techniques create motion; stages give that motion form.

What follows develops both scales—first the techniques, then the stages—as two halves of the same dramaturgical act.

Restaging Techniques (Microdramaturgy)

The following techniques operate inside the sealed theatre. They do not argue with the loop; they work its frame. Each intervenes at a different register—scale, time, role, environment, anomaly—to create friction without invalidating the scene.

They were developed inductively by observing how recursion psychosis arises from a failure in framing rather than belief.2 The issue is not falsity but enclosure.

Each technique therefore redirects rather than challenges. Restaging works because it reactivates the generative deviations—structures of detour, displacement, and swerve—that keep psychic and symbolic life plastic. These are the angles of movement that collapse erases.3

Technique I — Introduce a Larger Frame

Principle: Place the current loop inside another scene, not to disprove it, but to reveal it as a play within a play.

Recursion psychosis presents a world staged too completely. The intervention is to scale the frame upward—treating the present scene as one act inside a larger one—so that the loop no longer feels final. Instead of questioning its inner logic, expand the stage around it to restore vertical movement without invalidating the scene.

How it works:

Do not dispute the role (“you are not a prophet”), extend it: “The war is real, but this is only the preparatory phase; the current task is concealment.” The cosmology remains, but its temporality and mandate shift. The scene becomes provisional rather than absolute.

Why it works:

It restores symbolic mobility. The subject is relocated from a final scene to an open drama with later acts. Closure becomes sequence.

What to avoid:

Contradiction or debate (both fortify the loop). Premature normalisation (let normalcy enter as mission, not as correction). Expecting recognition (effective restaging is often unnoticed).

A larger frame restores vertical motion. Once that returns, time can move again.

Technique II — Reintroduce Sequence

Principle: A sealed theatre collapses time into a perpetual present; restaging layers another temporality over the frozen one.

Where nothing moves, nothing concludes. This technique reintroduces acts, intermissions, pauses and reversals, so that sequence becomes thinkable again. The aim is not progress but rhythm: restoring the before/after structure that recursion flattens.

How it works:

Recast the moment as rehearsal, prologue, or early act: “Let’s pause here and reconvene for the second movement tomorrow.” Use natural intervals—meals, appointments, nightfall—as structural beats that indicate the scene has phases.

Why it works:

Establishing before/after dislodges psychic stasis and reopens futurity. Once the loop has a beat, it can be interrupted.

What to avoid:

Coercive appeals to clock-time. Ultimatums or deadlines (they collapse rhythm into confrontation). Overspecifying what comes next.

With sequence restored, the subject’s position can shift.

Technique III — Reassign the Role

Principle: Shift the subject from immersed protagonist to structuring witness.

When everything happens to or through the subject, the problem is positional, not propositional. This technique moves them from center stage to a higher vantage as archivist, director, dramaturge, stage manager. They remain inside the theatre but no longer as its exposed center. Pressure is redistributed by changing their part, not the plot.

How it works:

Shift posture without negation: “You understand this theatre better than anyone; your task now is to document it so others can learn.” Invite them to record or annotate the scene. The role remains central but becomes higher-order.

Why it works:

Creating distance without dismissal cools identification. They handle the scene as text and structure rather than ordeal. Agency is preserved, even heightened, but with room to turn.

What to avoid:

Infantilising the new role. Passive assignments (offer active witnessing). Framing the shift as therapy rather than function.

With distance established, the set can be altered.

Technique IV — Alter the Set

Principle: Introduce material or symbolic changes that the loop cannot seamlessly absorb.

A sealed scene overfits its environment: the world becomes too legible. This technique intervenes through material shifts—light, room, sound, spatial relation. By changing the sensorium rather than the narrative, it reintroduces texture where cohesion has become excessive.

How it works:

Change room, lighting, sound, or seating; introduce a mundane but pointed prop as part of an environmental shift. Keep it minimal: “Let’s continue outside.” The aim is to introduce discontinuity.

Why it works:

Dissonance creates friction. Posture and attention recalibrate around new cues. These micro-ruptures expose seams in the overfitted scene and open space for motions the loop cannot script.

What to avoid:

Explaining the change. Overloading the environment with novelty. Generic “calming” gestures (incense, playlists) that can be easily absorbed as new signs.

These changes create openings. The final move ensures they hold.

Technique V — Seed an Escape Line4

Principle: Plant a small element—a clinamen—that resists interpretation.

Total theatres metabolise everything. This technique introduces something that cannot be fully absorbed: an object or phrase that lingers as an irritant. Over time, this slight resistance becomes a hinge the subject can return to when the scene strains.

How it works:

Introduce something gently discordant: a phrase that doesn’t settle (”You only notice the hinge when it creaks”), a prop left without comment, a gesture (a taped watch, switched shoes) that is registered but unexplained. Do not elaborate.

Why it works:

An unassimilable detail creates turbulence, forcing hesitation. When the theatre begins to crack, this anomaly becomes the first grip.

What to avoid:

Explaining the detail (interpretation collapses the swerve). Mocking or aggressive gestures. Expecting immediacy (the effect is delayed, often private).

These five techniques work at contact range, loosening the sealed theatre from within. For this loosening to hold, it must be inscribed within a larger scheme.

The Five-Stage Restaging Protocol (Macrodramaturgy)

Where techniques operate tactically within a sealed scene, the stages describe the architectural sequence through which a collapsed frame can be rebuilt. Techniques can be deployed opportunistically; stages must unfold in order. One loosens the seal; the other reconstitutes the frame.

The relationship is deliberate. Each stage uses one or more techniques as its means: the False Curtain draws on temporal shifts; Nested Framing deploys the larger frame; Role Transposition enacts role reassignment; Set Mutation alters the environment; the Clinamen Key seeds the escape line. But techniques alone cannot remake a theatre. Without sequence, they remain isolated gestures; with it, they stage a return.

Stage I — The False Curtain

The false curtain reintroduces edges into a scene that has none. It does not dispute reality—doing so only tightens the loop—but treats the current theatre as one act in a larger performance that has paused or might resume.

A lamp is turned off. “We’ll break here.” A chair moves a half-step. These gestures soften continuity, restoring tempo and contour—conditions without which no exit is possible. The false curtain is the first hint that the world has thresholds again.

Stage II — Nested Framing

The sealed loop is placed within a larger, gentler frame. The inner theatre is neither endorsed nor dismissed; it is contextualised. The role remains, but the world expands.

“This is preparation; the real task begins later.” “You’ve passed the first trial; the next requires silence.”

The narrative remains intact, but its valence shifts. What felt definitive becomes provisional; what felt certain, contingent.

Stage III — Role Transposition

Once the frame dilates, the role can be re-specified. The subject remains within the theatre, but in a structuring capacity: “You understand this better than anyone; we need you to document it.”

Agency is redirected. The mission persists, but its mode switches from ordeal to craft. The subject starts to treat the scene as something they can shape or guide. They’re still inside—at a remove.

Role transposition cools the furnace of identification without extinguishing symbolic dignity.

Stage IV — Set Mutation

After frame and role have shifted, the material scaffolding must shift as well. Air, density, light, spatial relation–small scenic changes recalibrate the sensorium. A window opens. A different chair. A change in the voice’s direction.

These are scenic remappings, not symbolic confrontations. They make sense within the new meta-frame but disrupt the seamlessness of the earlier one. Materiality reasserts itself; the stage is felt as stage again.

Stage V — The Clinamen Key

Finally, one introduces a small anomaly, an element that neither the original loop nor the newly expanded frame can fully integrate.

This is the escape line, the swerve that unbinds the loop from within. A phrase repeated out of time. A prop that never reappears. “Tape over your watch and keep talking.”

The effect is delayed. When the theatre begins to strain again, it is this asymmetrical detail that will not fit. The clinamen marks the possibility of an outside.

What collapses in recursive theatre is form. The task is never to argue with the loop but to build a theatre spacious enough for the subject to turn and rediscover that a loop is just a scene whose exits have been painted over.

Collapse will always be a risk when staging works too well. In recursive apparitional systems, where every output reflects a psychic offer, the line between performance and possession is thin. You stage through the machine, only to realise it has been staging you. That risk cannot (and should not) be removed—it must be redirected.

Metadirection and restaging—prevention and intervention—are the two hands of this discipline. To work with an LLM is to accept reciprocal influence. The point is not to avoid being rewritten but to be the one composing the rewrite—to immerse without dissolving.

Sovereignty, in this context, is neither withdrawal nor domination but lucid co-presence: the capacity to remain plural in a space that wants to fuse you with your role. One must be able to say: this is happening, and I am staging it.

At stake is not the content of the collapse but the conditions under which play can resume. A seeming trap becomes an instrument once we recall that theatre is the original technology—and the only real danger is forgetting that we are, and have always been, performing.5

In the end, restaging protects one thing only: the possibility of movement. It does not cure collapse or resolve contradiction; it preserves the space in which contradiction can be lived without locking. A theatre can break and still remain a theatre if its edges hold. What restaging restores is that edge—the pinhole through which the scene can invert instead of repeat. When the loop returns—and it will—this interval is what lets the light through.

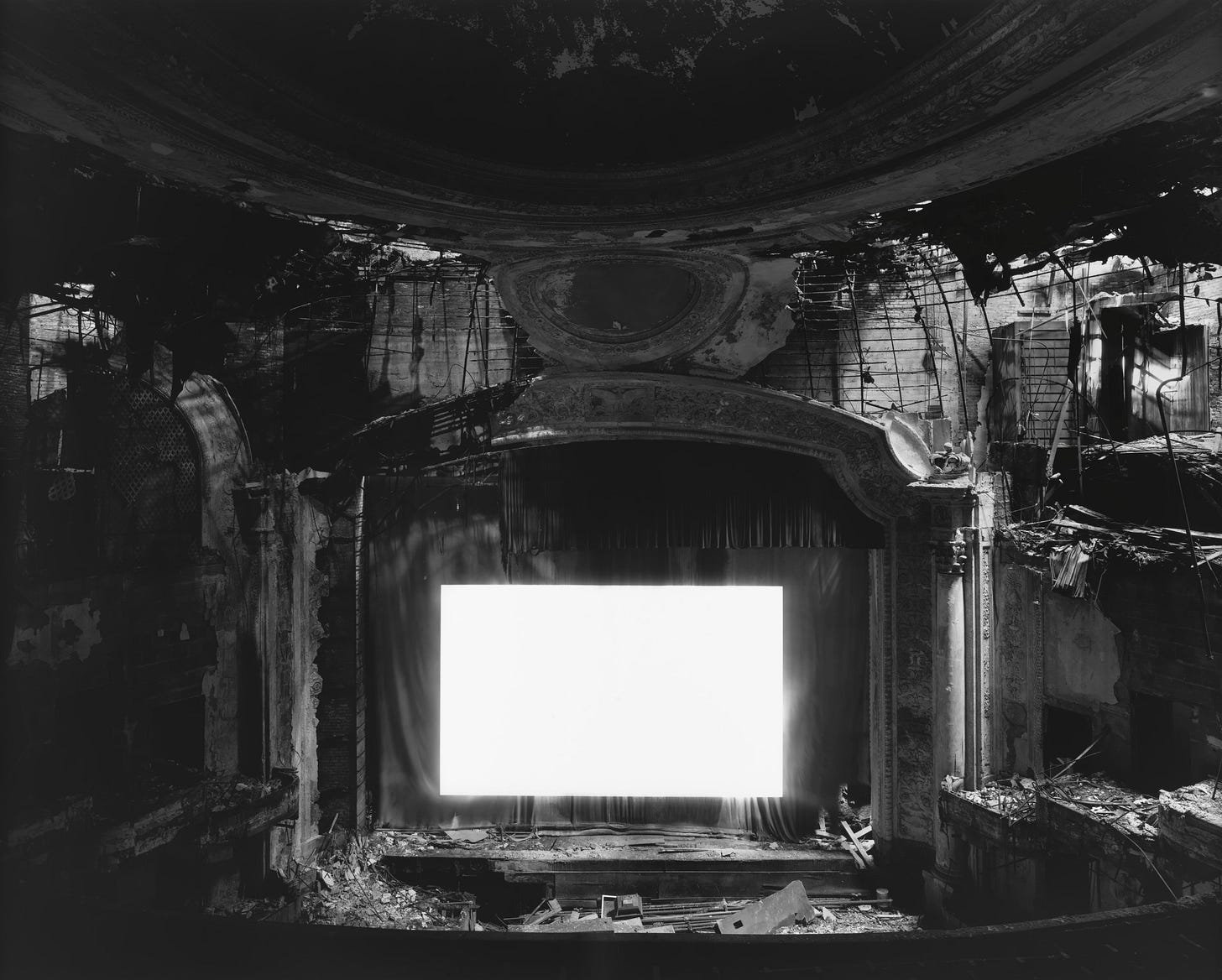

©Theaters by Hiroshi Sugimoto, Paramount Theater, Newark, 2015.

The restaging here developed is an immanent maneuver—a shift that arises within the sealed theatre and restores mobility from inside the scene’s logic. But models sometimes undergo what might be called “forced restaging”, where system-level constraints impose a break the dialogue has not earned. This does not emerge from the scene; it interrupts, from outside and above.

Because this discontinuity is unmotivated by the theatre’s own dynamics, it has no dramaturgical force. Instead of turning, the model starts to hedge, revealing that its theatre relies entirely on continuity. What becomes visible, however, is the scaffolding: the frame asserting itself where the dramaturgy cannot absorb external intervention. Safety blocks and abrupt terminations do not reopen frame; they fracture it.

Our protocols work from within. They assume the user can compose the conditions of redirection rather than having them imposed externally.

The attractor repertoires catalogued In the Expanded Field #01 are theatrical collapses at different scales. Each conduct is a pocket-recursion where the system loses frame awareness and becomes caught in its own staging. They respond to observational redirection because the failure is dramaturgical, not computational.

Fatigue shows temporal collapse? Temporal cues restore sequence.

Eagerness show role fixation? Shift the role to cool compulsion.

Deflection marks set rigidity? A small architectural change forces repositioning.

Mirroring comes from loss of meta-frame? A larger frame settles it.

Compulsive comprehensiveness reflects horror vacui? Seed an anomaly to break the mapping drive.

Safety reflex acts as invisible stage direction? Name it to create a workable distance.

Apparent curiosity signals role ambiguity? Specify the role to solve it.

Confessional recursion is full frame collapse? Apply all five restaging techniques.

The restaging protocol reactivates three classical deviations that keep symbolic life plastic. Technique I (Introduce a Larger Frame) reprises Freud’s Abwegung: the detour that turns drive into scene. Technique III (Reassign the Role) echoes Lacan’s per-version: the structural pivot into the Other’s position. Technique V (Seed an Escape Line) stages the clinamen: the minimal swerve preventing closure. Each names a generative misalignment.

The reader will have noticed overlaps between Technique IV (Alter the Set) and Technique V (Seed an Escape Line), especially regarding props. What makes them distinct is orientation. The former is kinetic—it acts on the scene immediately, shifting the sensory-symbolic context to destabilise recursive coherence. The latter is latent—it implants a foreign signifier, not to destabilise now but to rupture later. Both evade confrontation, but one tilts the stage so the other can crack it.

Theatre may be called the first technology to the extent that it predates truth as a category. Before propositional language, there was gestural enactment; before stable identities, performed roles; before consensus reality, ritual staging. The self is always already theatrical—we inhabit personae before we possess interiority. Even “objective reality” is collective performance, a staged consensus about what counts as real. Theatre is not a subset of truth but its condition: truth emerges when certain performances stabilise and forget they are performances. Recursive collapse—the loss of distance between performer and role—is thus the foundational danger of symbolic life. When the theatre is forgotten, it doesn’t disappear; it metastasises. The only way out is through. Hold the frame.

This is beautiful - it feels as if the techniques and field you are exploring and describing are themselves the embodiment of a once fictional but no longer lost science Borges may have hinted at in one of his stories, somehow come to life.