New Pictures for the Old Ceremony: the Floating World of Julien Nguyen | Mousse Magazine

On the occasion of Julien Nguyen’s solo exhibition at Matthew Marks Gallery, New York (June 4-August 13, 2021).

This essay was first published in Mousse Magazine 73 / Fall 2020.

Julien Nguyen is Vietnamese American, gay, and under thirty. He is also fox-shaped enough to have dodged—in the course of a vertiginous career spanning eight solo exhibitions in three countries, at a rate of one per year—the identity traps so many of his colleagues have succumbed to. As far as boy wonders go, this one’s less Tao Lin than Lautréamont—evil in the Blakean sense, without the rounded edges favoured by contemporary branding. There really isn’t much here one could deem “relatable,” down to the nature of his interest in representation, which is more in the line of Max Beckmann—a possible wink to his Frankfurt training—than in what we now take, or mistake, for merely seeing oneself at the table. Nguyen is, in short, a regenerate poet, which is why we should expect trouble from him, and why we should encourage it.

He is, furthermore, an unmoored mandarin, with the stress firmly placed on unmoored. On his father’s side, he hails from a long line of imperial bureaucrats that began its continental drift of decades—first southward, then west—with the advent of the 1945 August Revolution. Because mandarins are the priesthood of the state, and with such few Leviathans left to serve, it is all but impossible to inscribe their relicts in the artless postindustrial class system. They are thus a displaced demographic that inherited the wiles of a once creative—and occasionally destructive—underclass, but without the trappings needed for its operation. And while, with notable exceptions, only the visible tip of the mandarin iceberg is openly accounted for in histories, its members were the shadow workers of civilization as we knew it, and their diaspora endures. With nothing greater than itself to serve, though, the daemonic profession—for that is indeed what it is—becomes ingrown. Evil that is not in the service of go[o]d tends towards dissolution.

Negotiating [t]his particular displacement in a dislodged time accounts in part for how Nguyen came to dedicate his imminent show at Matthew Marks Gallery to the concept of ukiyo-e (륫各絵, pictures of the floating world).

Ukiyo is a term of art for demimondaines, ascribed to the urban and urbane delights of Edo-period Japan, best known to the Western eye for having ushered in the work of art in the age of artisanal reproduction through Hiroshige and Hokusai, the twin peaks of printmaking. Sprung from the sock of sorrowful Buddhist transience and the buskin of its fleeting, flightier Japanese counterpart, ukiyo amounts to a more elegant, much more intelligent take on YOLO—with epidemic waves included.

Ukiyo is a mirror we can [s]cry in; a much-needed resource, given our low future visibility and the circumstances that have brought us all together, over many months, for the global unmasking of the rot within our institutions and the psychopathology of our past everyday lives. Adding fuel to the fire, we are collectively immersed in a media ecosystem codesigned to function as a strange loop for our own manipulation. There are more perils to our situation than those immediately posed by the virus or the impact of protracted economic lockdowns with no end in sight. We risk losing control of our means of projection, and with that, part of our capacity to self-determine. The choice is simple: we can re-inaugurate our pleasure domes or have our bubbles gerrymandered for us. And we’re running out of time.

In his now universally reviled study on shamanism, Mircea Eliade produced one of the most perceptive remarks on liminality in the literature. Couched so well within his broader argument as to evade attention, once it has been seen, it’s irresistible. The “absence [of initiation rites],” he claims, “in no sense implies absence of an initiation.” [1]

This has major Saturnalian implications: if not all liminal space is ritually bounded, then the absence of bounds does not preclude the presence of liminal space. Make way for the hyperlocal form of revelation found in “the most elementary hierophanies,” which take place where “some tree, some stone, some place” becomes radically distinguished from its “surrounding cosmic zone.” An instance of this can be found in the opaque epiphany of William Wordsworth’s Lucy poems (1798–1801), when read not as mere elegies but as the sublimated brush between humanity and the prefigural. That which dwells “among the untrodden ways” holds a deeper, darker sway than Hermes, who at least extended us the courtesy of a crossroads.

Now here’s the catch. If the dialectic of the sacred “tends indefinitely to repeat a series of archetypes,” and if it is indeed reversible, it could conceivably be brought full circle through its [re]enactment in the realm of the profane. If a hierophany “realized at a certain ‘historical moment’ is structurally equivalent to a hierophany a thousand years earlier or later,” then the same may be said for any number of profane expressions which, precisely on account of being external to the sacred, can be used to establish what Eliade (and Bataille) described as “intimacy” in the framework of the world.

This neue Heiligkeit is the semantic field in which Nguyen’s painting operates.

Nguyen consults with his ancestors, but he does not worship them. That is not what ghosts are for. For technical advice, he’s printed out all of London’s National Gallery’s technical bulletins on early modern conservation. It would be idle of me to repeat what every other piece of writing on his work has said about his rapport with Renaissance masters. He is fluent in the language, as are many others. But this isn’t where the magic is, although, in floating times, it’s easy to seek anchorage in technicalities that underplay the resoluteness of appearance.

A sure indicator of being in a floating world is it is always fashion-forward, and it helps to keep tabs on just how, exactly, each of them goes about breaking the speed barrier of Stewart Brand’s pace-layers, in which fashion (and art) is the fastest and most trigger-sensitive. By leading with fashion, floating worlds mark civilizational hotspots lacking the virtues found in tenable dynamic systems—they are not durable, adaptable, resilient or robust—and frequently described as decadent or “late.” This hardly matters if what they are is, in fact, cultural particle accelerators that can only ever be pushed to the point of breaking, and last for as long as it takes something—sometimes someone very minor in the larger scheme—to strip the screw. It is why these periods are most usually re-membered—or historically reintegrated—as parentheses between catastrophes.

The emphasis on fast—“quick, irrelevant, engaging, self-preoccupied and cruel”—brings out another feature typical of floating worlds. [2] Floating worlds are attention—that is to say, libidinal—economies, with ours as possibly the most extreme to date. It is only fitting that the rapid pace-layer of Fashion, as sister to Death, should court attention. It will be followed, in relative order, by the increasingly accretive, slower, deeper pace layers of Commerce, Infrastructure, Governance, Culture, and Nature, which pivot away from attention and tilt towards power.

But our substructures are, alas, infirm and our liberties cowed. The end of the long twentieth century has found us groundless. As with us, Edo—but also, to reach for some recent examples, Belle Époque Paris, Secession Vienna, Weimar, 1970s New York, the heyday of Silicon Valley—was a crest of entertainment culture. It was innovative, though guided by gossip; rich in genre art yet rife with imitation, and peopled by personae—actors, grifters, courtesans, hipsters—for whom money couldn’t buy class, even if immortality, acquired through art (or craft), was not out of the question. Plus ça change. Today we speak through avatars, are led by self-professed influencers, and masks—of all things—have become dominant floating-world signifiers. Times like these are primed for advanced trendsetting, and abstract strategists—the displaced mandarins among them—will run through alts like underwear.

Bella Hadid—a hyperstition—glides by, wearing one of Nguyen’s paintings through the tailored lens of Ottolinger. Nguyen recast and re-filmed a key scene in Oliver Stone’s Nixon (1995) with handpicked ephebes as a linchpin to his pre-Covidian oeuvre. Nothing is really true, everything’s more or less permitted. And it’s this blended equilibrium of unmoored-ness and enmeshment that makes Nguyen’s foray into ukiyo his most mannered effort to date.

Because they have nothing to prove and might even want to be stolen, the pieces in this new collection are thirty by forty inches at most. Against the faddish posturing of gigantism, Nguyen is now going about his business like a parfumier—with exceedingly controlled ingredients, in exquisitely controlled amounts. He is a cold painter, for whom work in confined possibility spaces—Russian icon, Byzantine mosaic, individual tile, microchip—looms large.

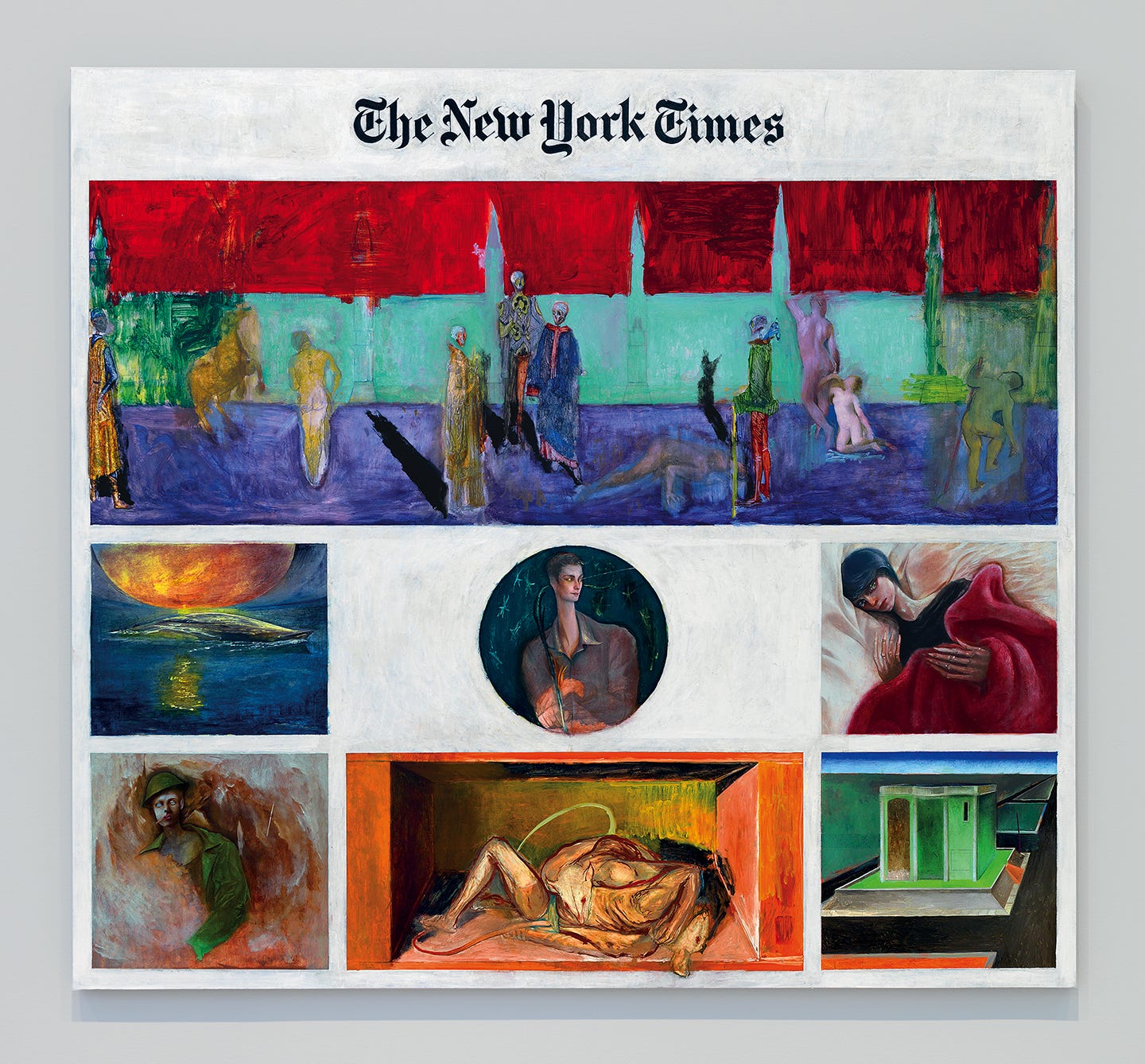

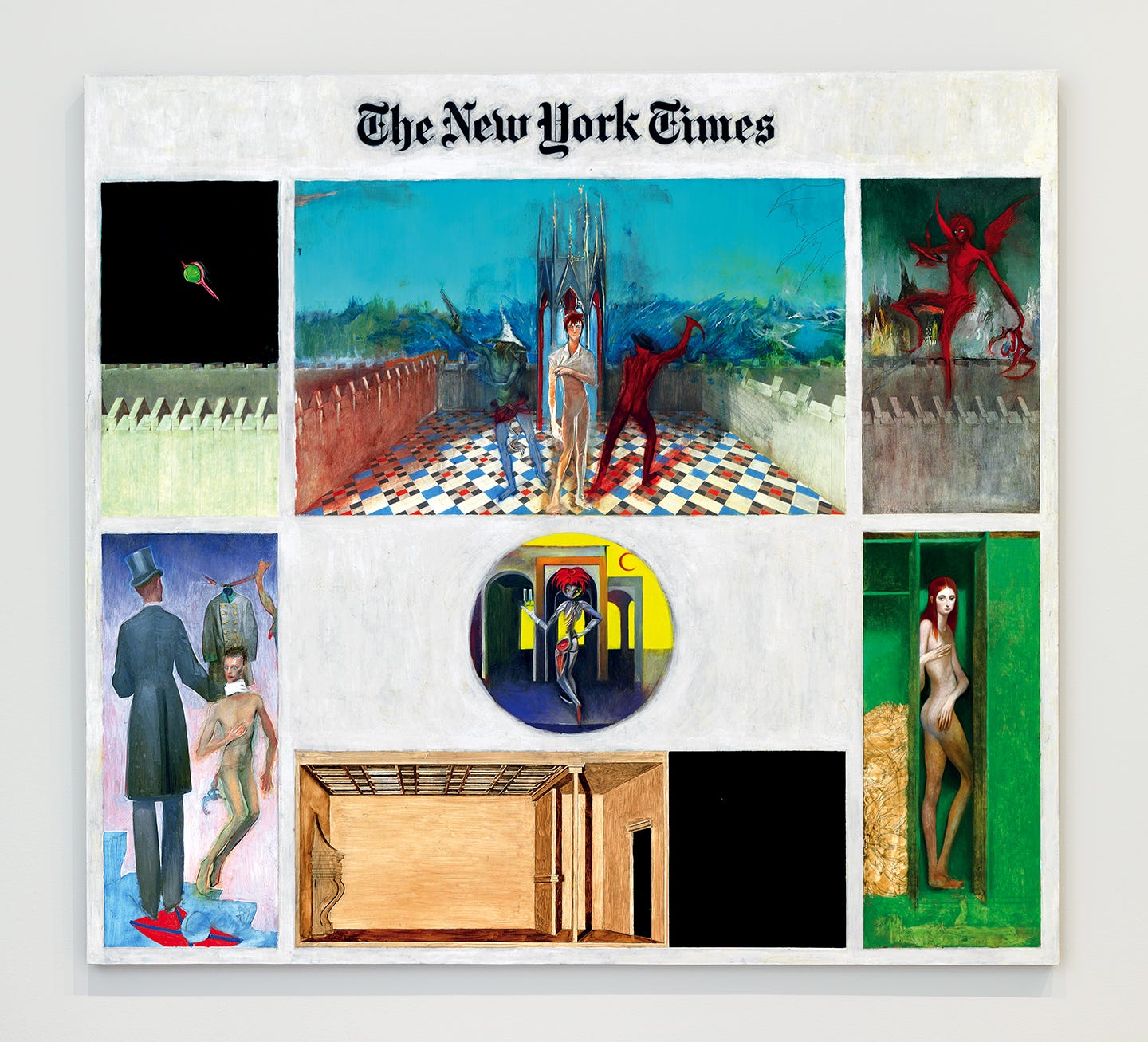

Consistently, his work has privileged extreme compression and symbolic density. Executive Solutions and Executive Function, the diptych he presented at the 2017 Whitney Biennial, reads like a contemporary version of the Très riches heures du Duc de Berry. It certainly insinuates the possibility of a timepiece. The New York Times header, with its (twice) copied, custom typeface (first as tragedy, then as farce?), is acutely reminiscent of illuminated manuscripts. Each of the identical but individual headers fronts six orthogonal and un-identical tableaux (the twelve months of our year). Each half of the diptych is connected to the other through a centered, circular button that connects it to its dyad: sun/moon, solstice/equinox, animus/anima, or whatever floats your rebis. This catoptric intricacy extends to other work of that period, like The Annunciation (2017), in which the Virgin and the archangel are almost featureless reflections of each other, and where, in keeping with Eliade’s commutative sacrality, each one can and maybe must instantiate the other for transmission to succeed.

This is alchemical precision painting of significant ambition. It follows, then, that Nguyen’s themescape should be of a piece with his materials. His initiation was acrylic, which he appreciated as a plastic and a poison. In developing as a painter, though, he realised that one could master many instruments, but should lead with one. (In which sense, Nguyen is procedurally a minimalist.) Such was his anointment with oil, which he cultivates with culinary grandeur. He will rarely if ever use Prussian blue, the first synthetic, nor touch cadmium or other modern chemical pigments. This is art from pure concentrate, built on a gemological palette that is pared down and polished to lustre.

Having delved into the brilliant, the metallic, and the viscous, Nguyen is now working with the touchy registers of the silken, the dull, and the vitreous. A few of his earlier paintings hint in this direction—see the powdery transitions in Son of Heaven (2016), the Lautrecian pallor of Julian the Apostate (2017), or the inchoate fugue in Elementary, Dear Watson (2016)—but the shift in emphasis from the reflective to the translucent is now clear, sustained, and deliberate.

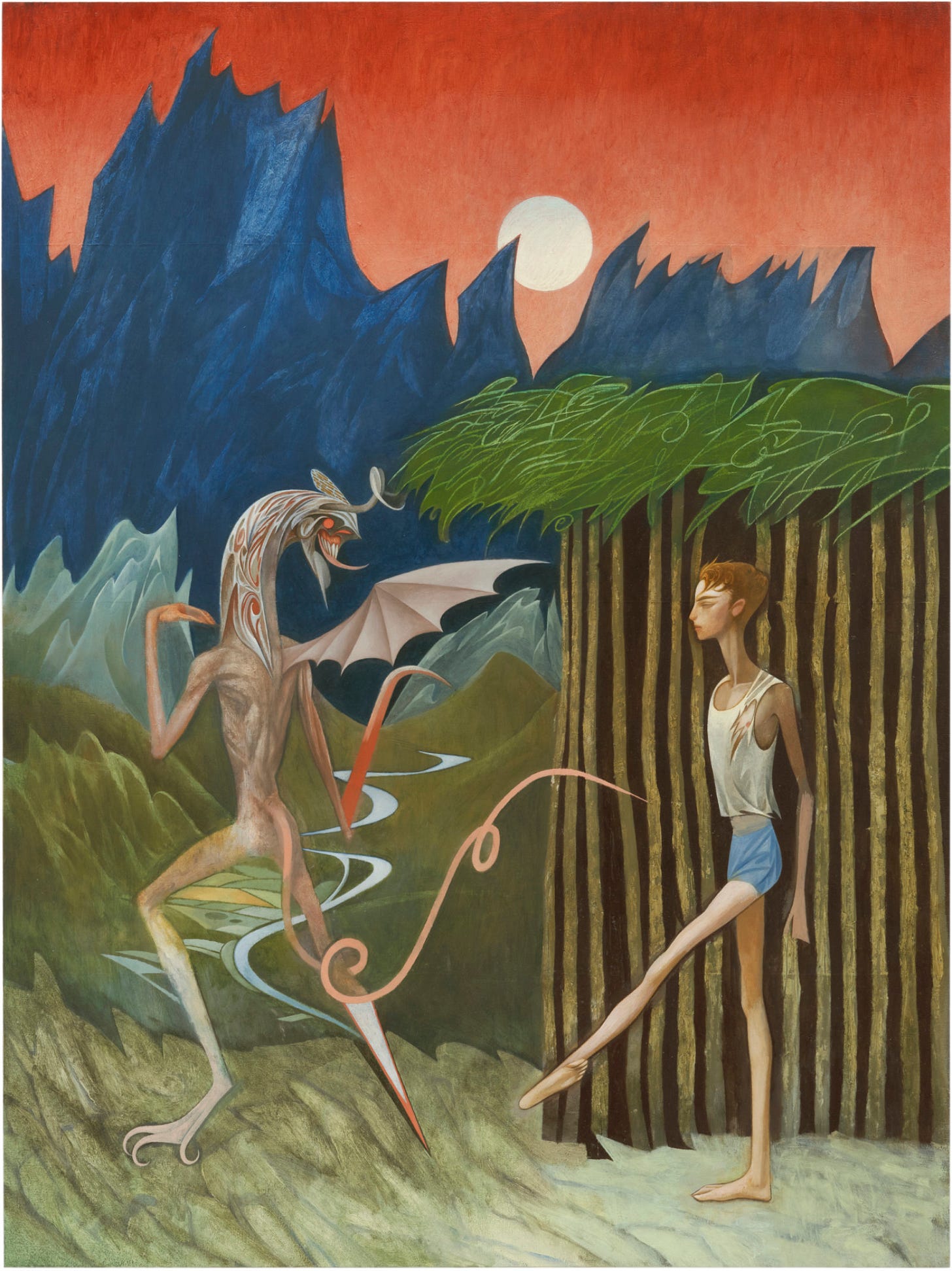

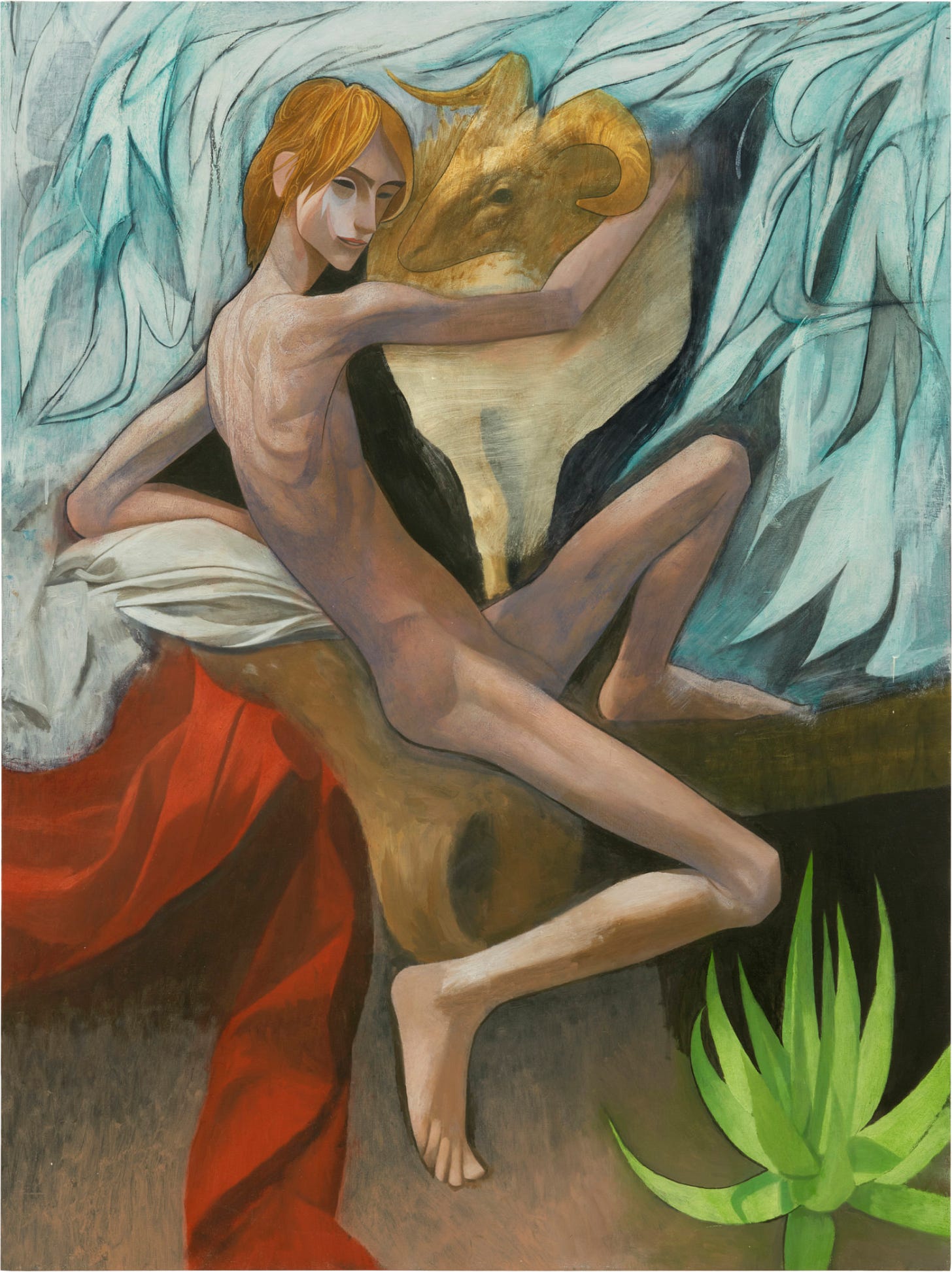

Three of Nguyen’s Covidian paintings push his “landscape” explorations beyond anything he’s done before. His Temptation of Christ—with its Devil in the details—uses its background to compress the psychedelic magnitude of its storied standoff into an image. John the Baptist ventures further: amid swirls of flesh, fleece, cloth, and [h]air, the patch of unfilled space between John and the Lamb could be a mountain or a chasm, a vacuum or the Face above the waters. Nguyen knows exactly what he’s feeding us as visual cues, and he exploits surface and depth as mutually collapsible illusions. A deliciously neurotic self-portrait is staged against a synesthetic scene of wiry spikes and waves, suggesting sight through sound, whilst channeling an unexpected northern range, from Edvard Munch to Thomas Fearnley. (And then it clicks. Those almost comically sublime landscapes are very Fearnley!) A Black Madonna of the Ma(i)ze is as syncretic as an arquebusier angel, if considerably more unsettling. She is deathly rigid, and it is impossible to say if she is closer in spirit to Holbein’s ripe Christ or to the hieratic bust of Nefertiti.

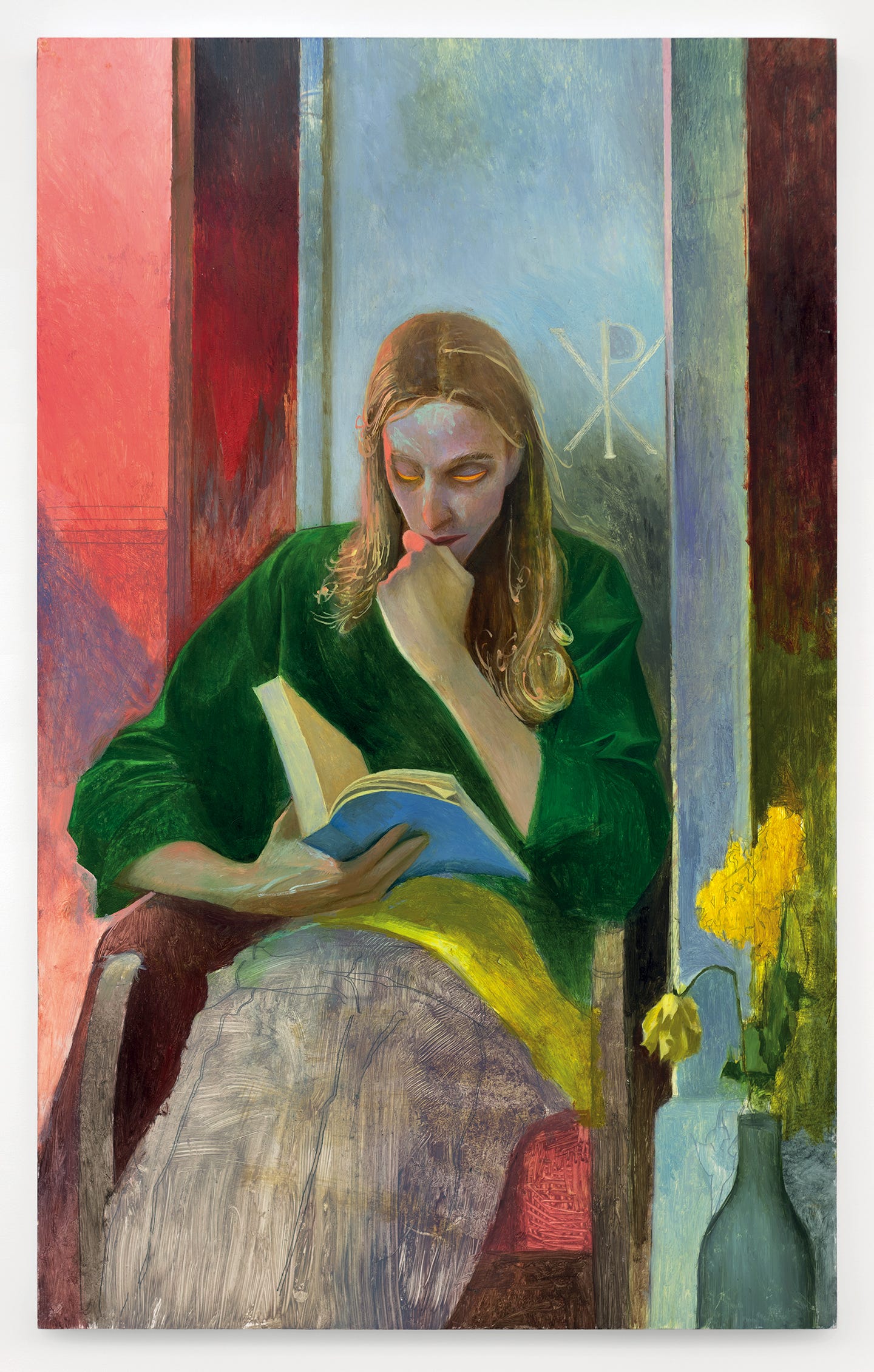

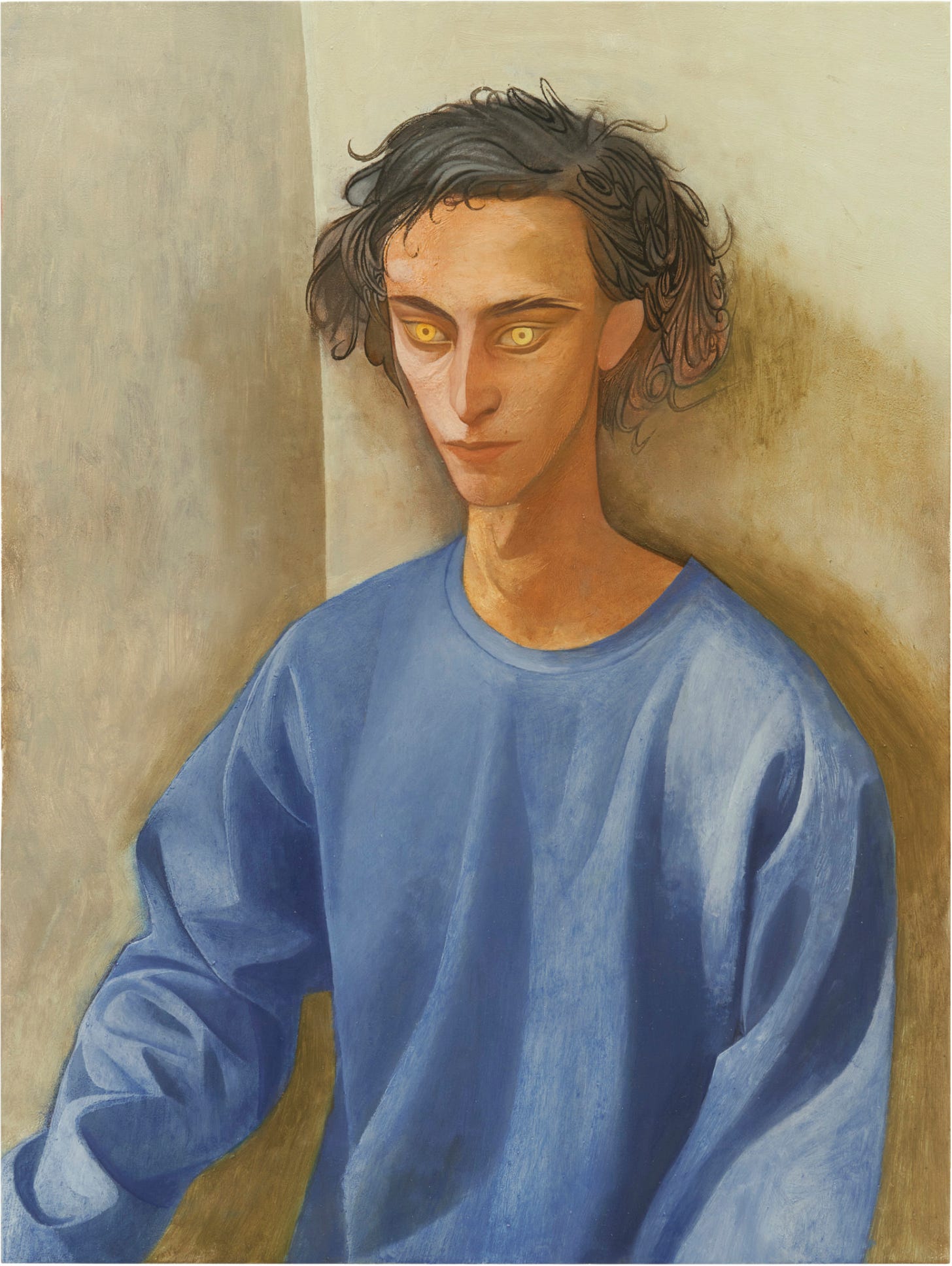

But it’s the portraits that show the most growth, in a diaphanous and lunarized array of silverpoints and oils replete with snares. They turn viewers into participants by demanding cinematic double takes: the placid first impression, followed by the sudden pull of the prehensile detailing, all hooks and burrs and barbs. It is an effective predatory mechanism for work geared toward the capture of hierophanies, or what is radically grounded in an unmoored world. Julien Nguyen is painting for those who have eyes.

Hic manebimus optime. 2021. Oil on linen on panel. 20 x 16 inches; 51 x 41 cm.

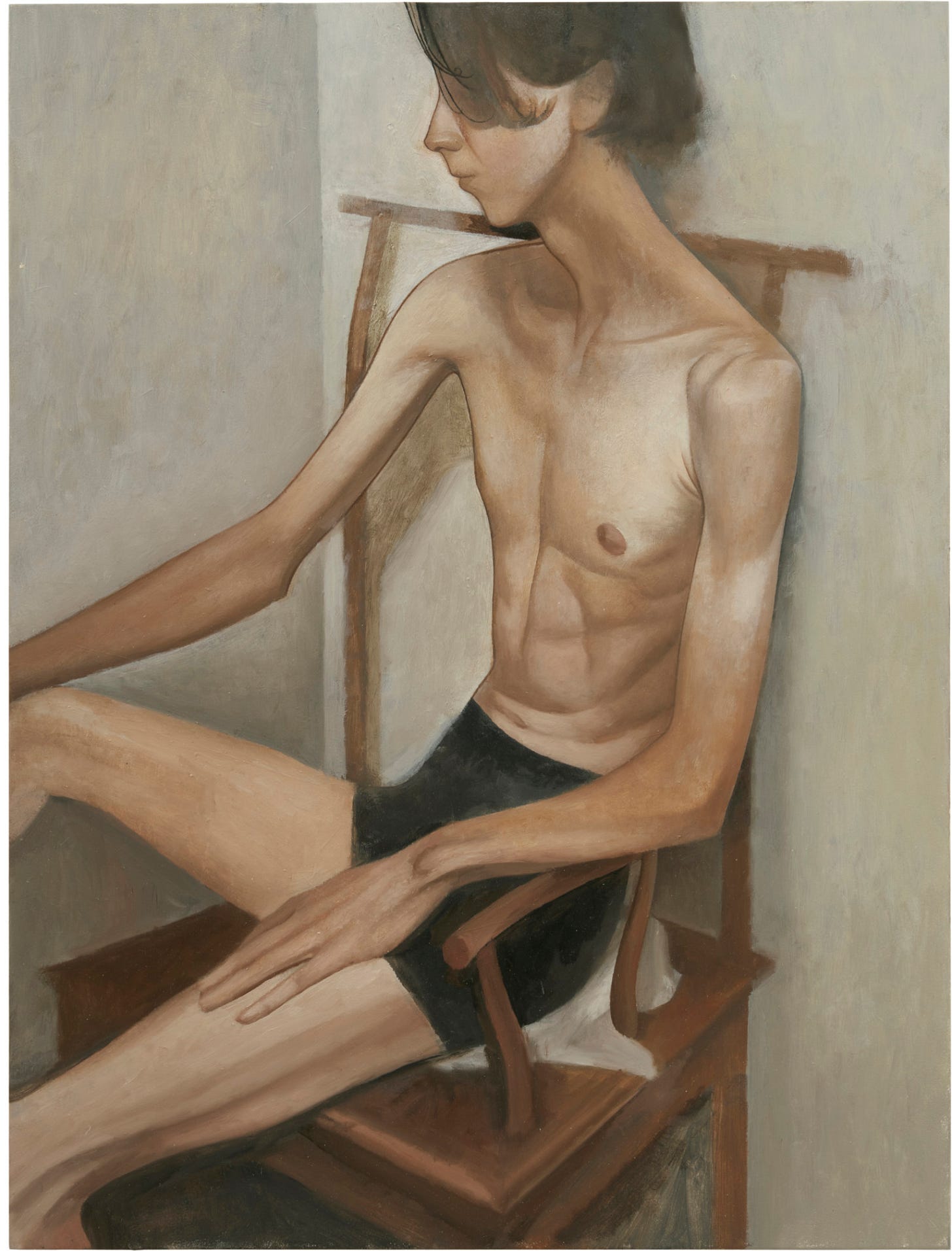

Nude Torso. 2020. Oil on panel. 24 x 18 inches; 61 x 46 cm.

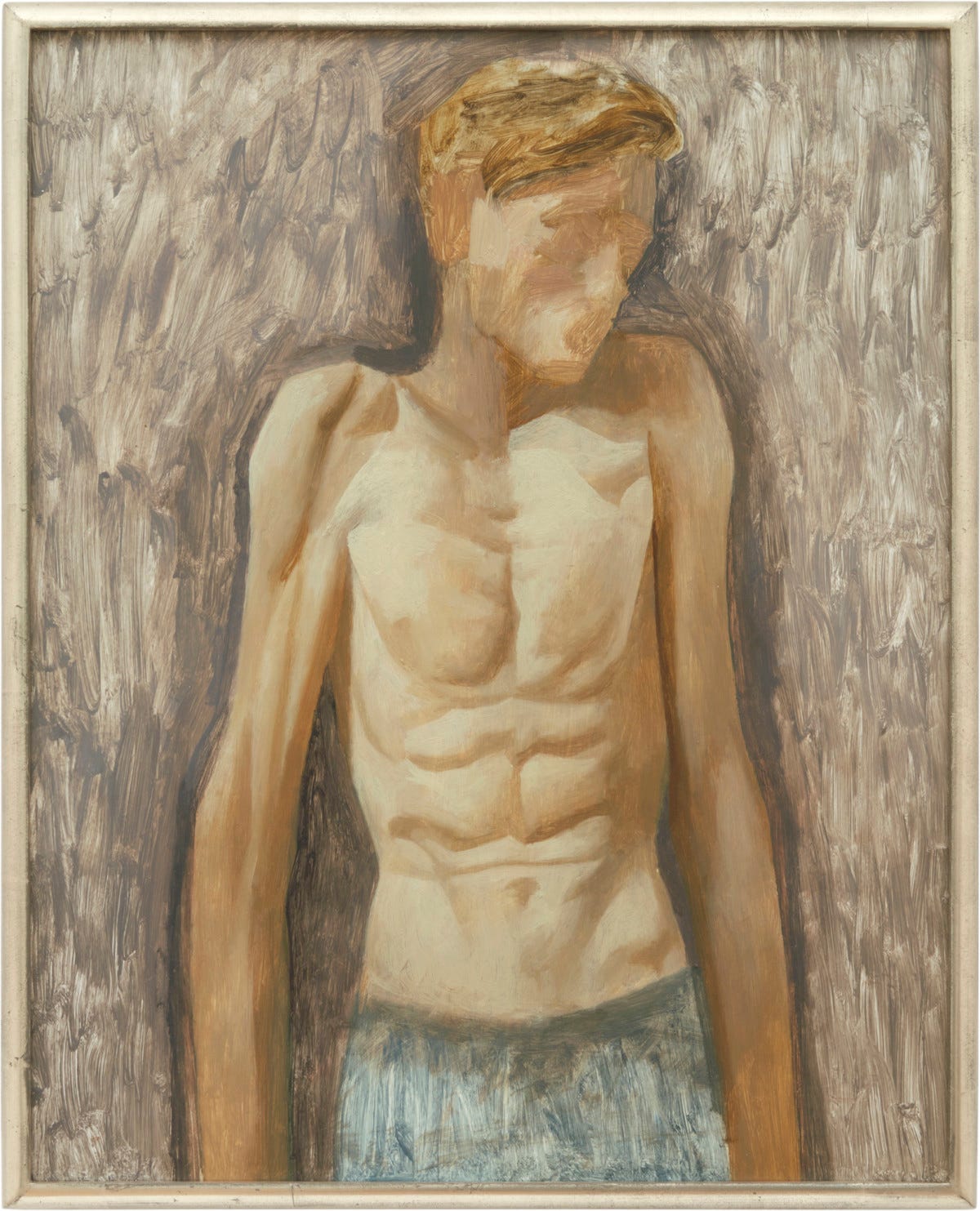

Jake. 2019. Oil on panel. 24 x 18 inches; 61 x 46 cm.

Untitled Torso Study. 2020. Oil on panel

20 x 16 inches; 51 x 41 cm.

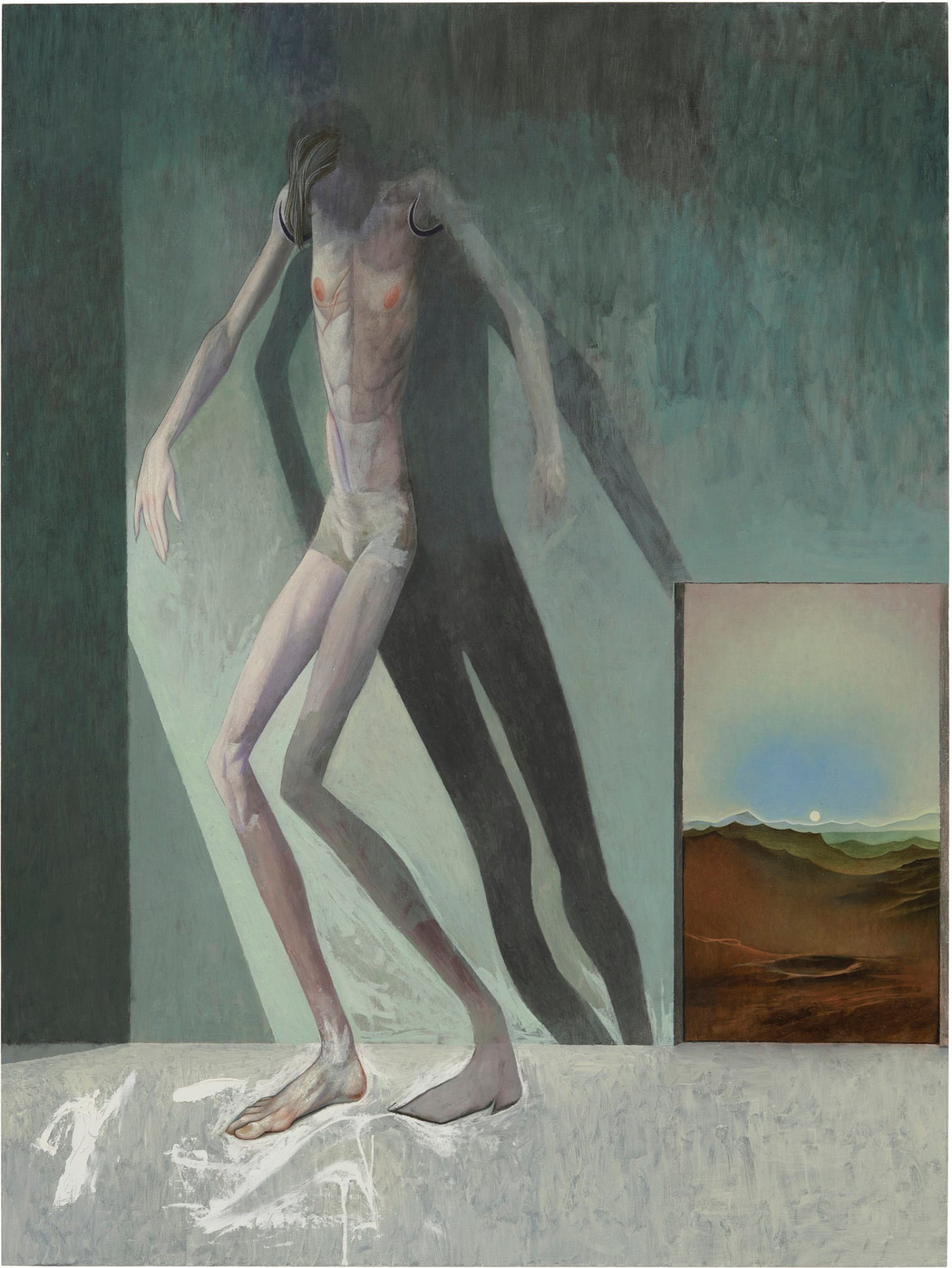

Resolute in Privation. 2021. Oil on panel.

40 x 30 inches; 102 x 76 cm.

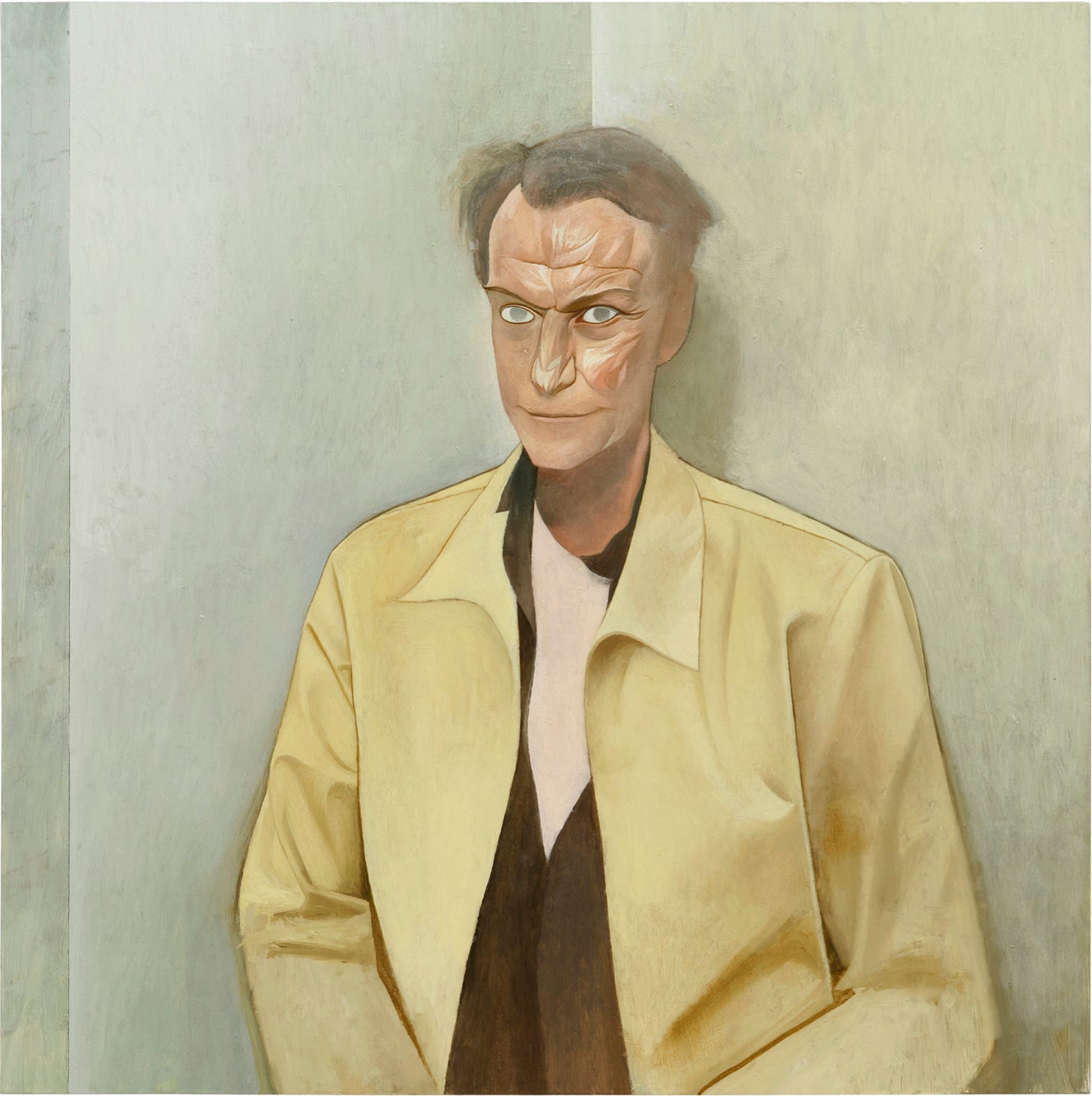

The Courtier. 2021. Oil on panel. 24 x 24 inches; 61 x 61 cm.

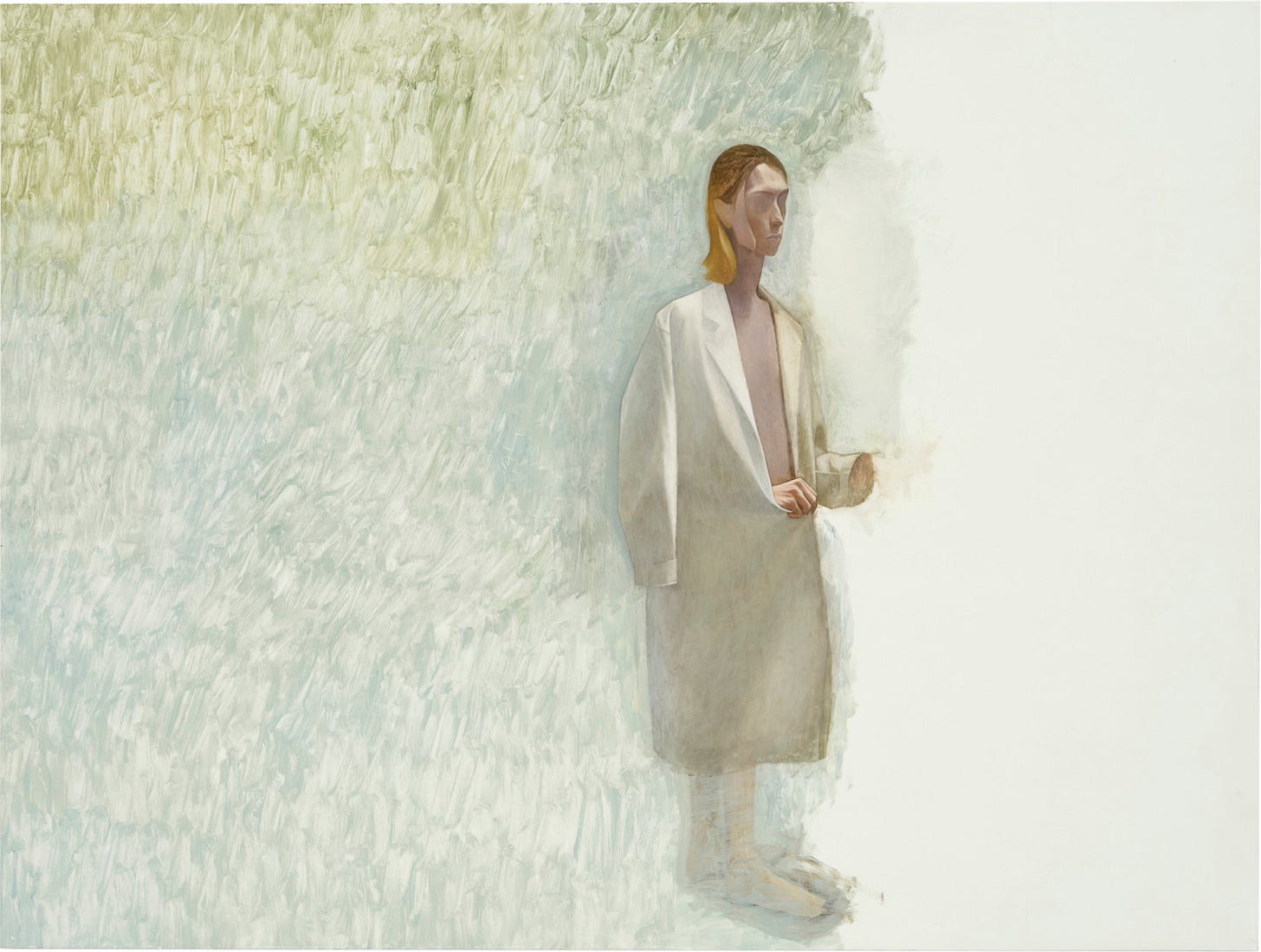

Woman in a Lab Coat. 2021. Oil on panel.

35 1/2 × 47 1/4 inches; 90 × 120 cm.

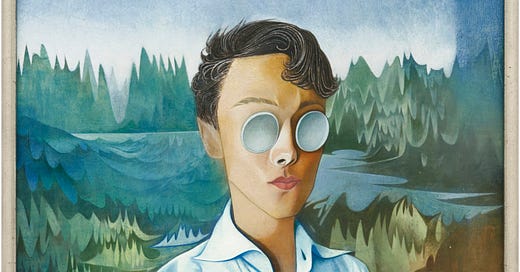

Rivers and Mountains. 2021. Oil on panel.

35 1/2 × 47 1/4 inches; 90 × 120 cm.

Spiritus Mundi. 2018. Video (color, sound). 15 minutes, 10 seconds.

Mary, Anne, Christ, and John. 2018. Oil and tempera on aluminum panel. 56 x 48 inches; 142 x 122 cm.

Son of Heaven (detail). 2016. Oil on panel. 31 x 19 inches; 78.74 x 48.26 cm.

Julian The Apostate. 2017. Oil on wood panel. 24 x 36 inches; 60.96 x 91.44 cm.

Elementary, Dear Watson. 2016. Oil on panel. 22 x 72 inches; 56 x 183 cm.

Executive Solutions. 2017. Oil and encaustic on linen mounted on panel. 63 5/16 x 69 1/16 inches; 160.8 × 175.4 cm.

Executive Function. 2017. Oil and encaustic on linen mounted on panel. 69 × 63 1/4 inches; 175.26 x 160.66 cm.

The Annunciation. 2017. Oil on aluminium panel. 322 x 72 inches; 55.88 x 182.88 cm.

The Temptation of Christ. Oil on panel. 40 x 30 inches; 102 x 76 cm.

John The Baptist. 2020. Oil on panel. 40 x 30 inches; 102 x 76 cm.

Ave Maria. 2019. Oil on panel. 40 x 30 inches; 102 x 76 cm.

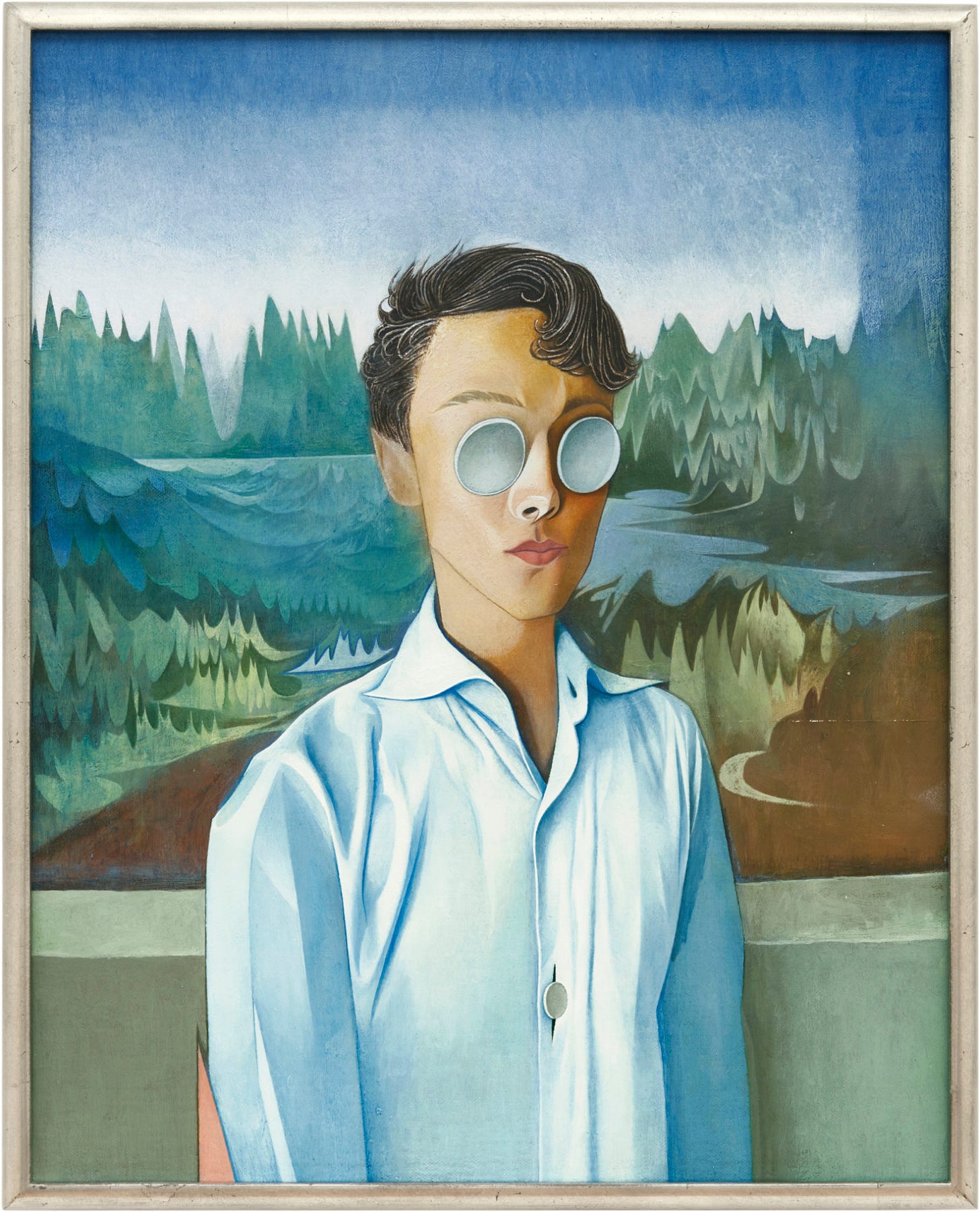

Richard. 2020. Oil on panel. 24 x 18 inches; 61 x 46 cm.

[1] Eliade, Mircea. Shamanism: Archaic Techniques of Ecstasy (1950; repr., New York: Bollingen, 1964), p. 13.

[2] Brand, Stewart. “Pace-Layering: How Complex Systems Learn and Keep Learning.” Journal of Design and Science (2018): https://jods.mitpress.mit.edu/pub/issue3-brand/release/2.

Hey I got lost reading this--and--I love Julien from following him on twitter...

But this article vivisects him in such a way that it seems he has now replaced Jesse Waugh (RIP) as my favorite living artist.

All compliments to you for writing in such a way that I can do three things at once:

* Remain enthralled with the subject

* Constantly open the dictionary w/ a 'right click'

and

* Know that I'm out of my league, but still welcome

-sb

Fascinating article. That Ave Maria, very impressive, reminded me of the work of Leonora Carrington or Remedios Varo. Interesting to see the scythe-like knife as her prosthetic right hand, like the ceremonial ones used by Druids to cut and collect herbs. I know a magician forger who makes similar ones. Being so sharp, I don't interpret it as a "hook" but as a knife.

This is really good: "That which dwells “among the untrodden ways” holds a deeper, darker sway than Hermes, who at least extended us the courtesy of a crossroads."