According to McLuhan, technology is the extension of our nervous systems. If aesthetics, as I claim, is the study of perception and affect as fundamentals of this neural growthspurt, its cathexis—that is, the social technology by which aesthetics can be harnessed, shaped, wielded and channeled—is theatre. Theatre is, in summary, performed applied aesthetics, and this is one of the reasons why its theory and practice have become so virtually indistinguishable from each other as to constitute the makeshift limits of The Real. “Theatres are founded to test or exemplify a theory”, writes Gerould, and so they operate as basically laboratories where hypotheses about reality and experience are honed via controlled, repeat performances—with no assurance of success. Similarly to the way in which a lab could be described as an experimental space for the design, building and testing of new technologies, the theatre is a laboratory for the research and development of new, extended nervous systems.

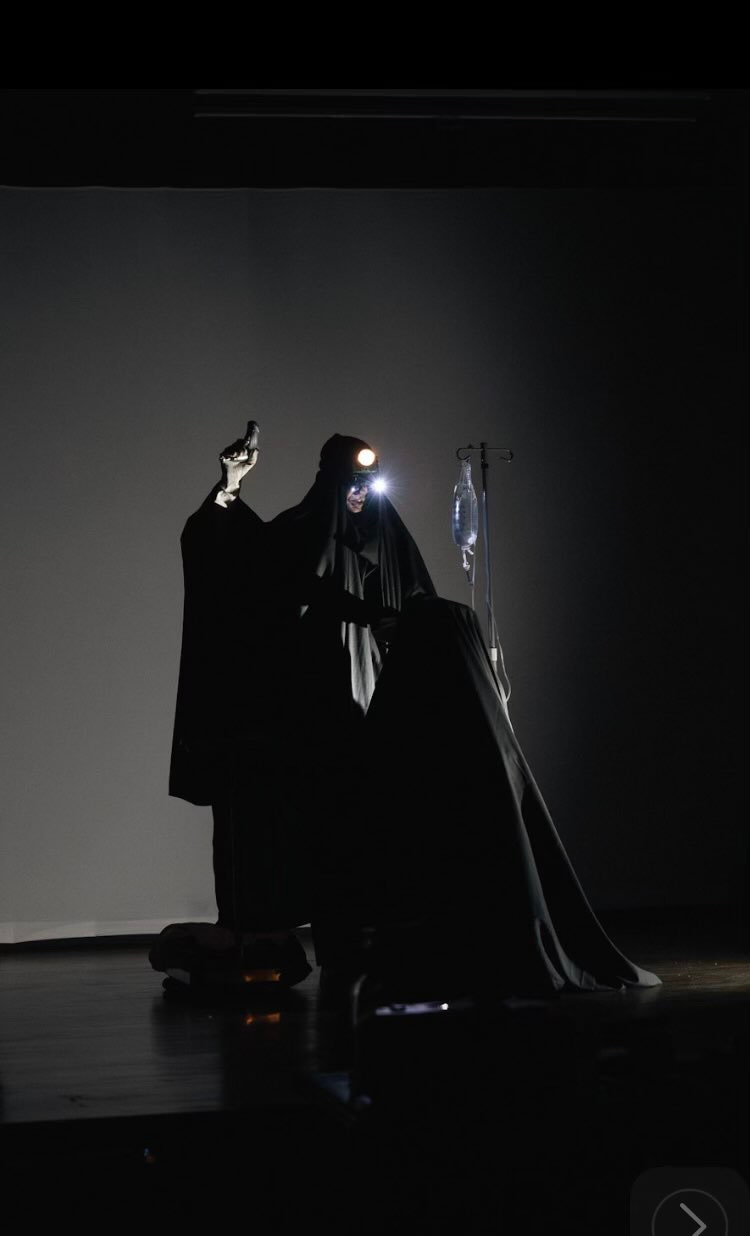

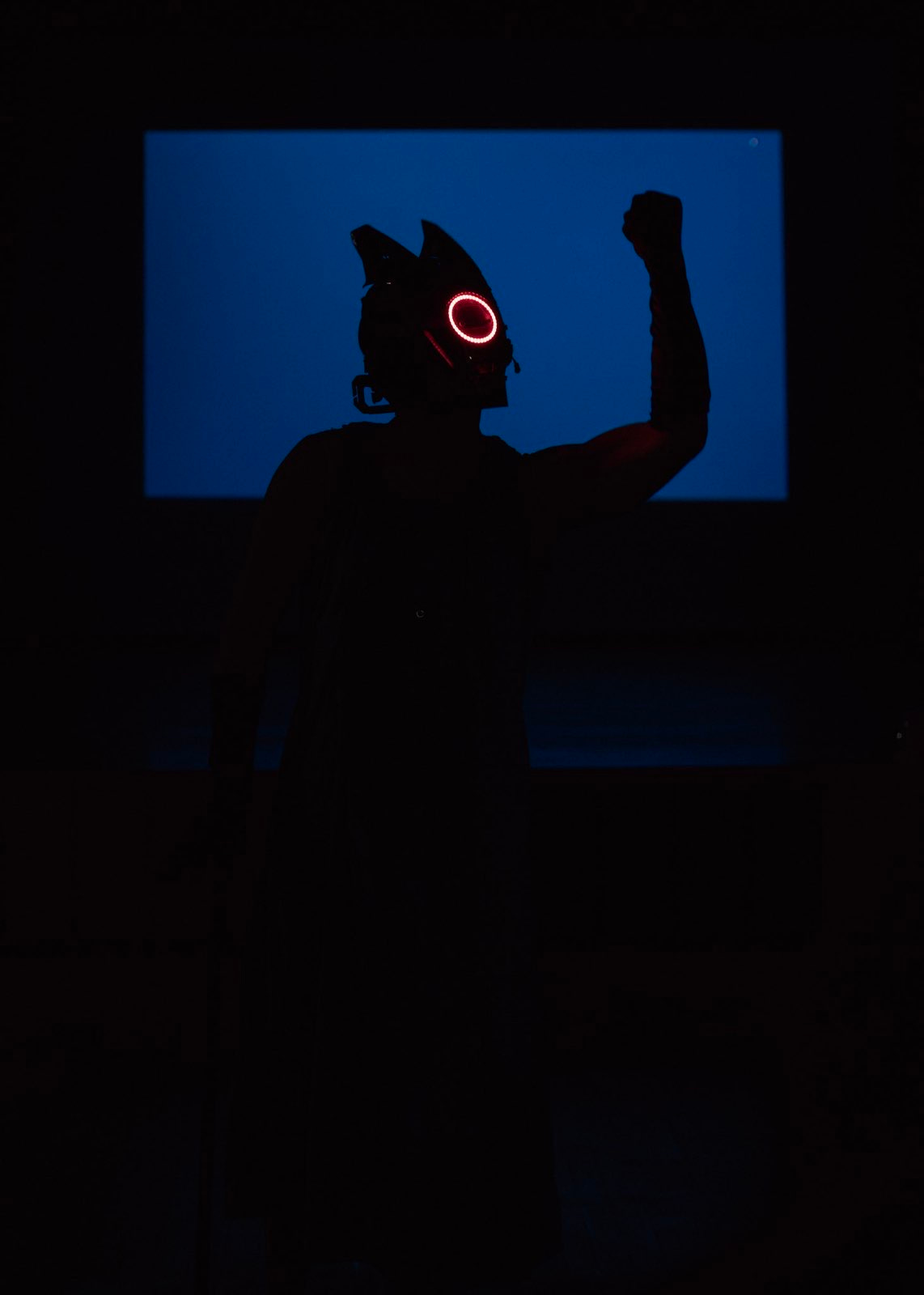

This is undeniably a trying task, and so the currency of theatre that’s practiced in this form is trial and terror: the plausibly unsurvivable aesthetic experience. In the same way in which, in Berry’s words, Butoh begins in the brainstem (and is, given its extremity and physicality, legitimately dangerous), Nasim Bleeds Green and Nanoblade (1998), Spring Break (2020) and The Mourning Light (2050)—the three plays that, in no particular order, comprise the so-called Sarcoma Cycle—have been written and should only be staged in this spirit.

That the triptych takes not merely sarcoma but the cycle as structuring motifs is relevant, especially because—with the exception of Nanoblade, an oncological variation on the myth of Orpheus and Eurydice—the presence of cancer is not immediately apparent in Berry’s trilogy. You have to know what you are looking for; from there, you have to find it where it finds you.

Cancer is not what these plays are about, it is what they are, or at the very least, what these plays mimic, in a way that resonates with how Klossowski described writing The Baphomet “as if I were describing a play that I was watching”. If, as Berry warns us in the introduction to Nasim, his “characters aren't characters: they’re deepfakes wearing actors”, the role of cancer in his plays does not correspond to that of a protagonist or even an antagonist. It is, in fact, that of an agonist: the substance that, when met with a receptor, sets off the physiological response; the muscle the contraction of which triggers the body electric. Anyone who understands how cancer moves—both its subversiveness and its explosiveness—will have no difficulty seeing this shape in Berry’s artful snake-handling of heat death. His mise en abyme includes his own performance as a playwright, his own grappling with the scope creep of his matter, which is Mimesis itself. The motifs in the plays are not just copied—as shown by the reams of memespeak in the dialogue—they are corrupted copies of themselves.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Covidian Æsthetics to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.