To Attack and Dethrone Gods | Ribbonfarm [expanded]

First notes on the terrorist artform

First version published @ Ribbonfarm on July 21, 2020.

Somewhere between readings of Sir Thomas Browne and Marcel Schwob, Borges finally met the archterrorist. He had no face left, only his accursed balance and a name shaped like a waveguide: Herostratus, arsonist of the second Temple of Artemis at Ephesus; punished with Oblivion, redeemed through Spectacle.

That Herostratus subsists among us by name, despite his damnatio memoriae, suggests something rather interesting about the range and possibilities of obloquy. It demonstrates that Spectacle is not constricted by situationist tropes, but rooted in the fundamental question of representation and so, of abiding art and world-historical interest.

For an idolatrous age that’s equally preoccupied with toppling statues and inventing heroes (aka preserving the status quo), I propose to bring Herostratus into the fold as representative of the auteur, or sovereign—the opposite of the activist. And it is critical for this line to be drawn, because our petty tyrants are so mindlessly [in]vested in transposing everything into a key of Re—resentment, reaction, revision, replacement, revenge—they have grown daltonic to the differences between the transcendental and the social-politic.

The distinction is, alas, essential to sovereign action, without which revolution or redemption are impossible (and why no aggregate tyrannical dogoodery will ever amount to one sovereign crime).

To cite Debord himself:

“[t]he growth of knowledge about society, which includes the understanding of history as the heart of culture, [and] derives from itself an irreversible knowledge, is expressed by the destruction of God.”

This is how Herostratus’ arson ushered in a new epochal climate, and why legend has it Alexander was born on the night the temple burned. At the endpoint of Zivilisation, worldwreckers beget worldmakers, and worldmakers beget Kultur.

As the cellular, lopsided shadow of the modern state, the terrorist organisation lays no claim to the Herostratuses of the world; who are individually, rather than ideologically, pursuant of attributions more intimate and more exclusive to the State―or, indeed, God―than any means-towards-an-end could be. Sic transit gloria mundi. Even in its religious variants, the terrorist organisation is mundane because its object isn’t glory. To become as the State, or like God, is to ensoul destruction—to be sovereign—no matter how fleetingly or at what cost. To “attack and dethrone God” through sovereign action—and there is no other way to go about it—is to pay off an entire world’s accursed share. (In this sense, Herostratus is not just more progressive than the entire Comintern, he is more Christlike than anyone currently strutting upon the world stage).

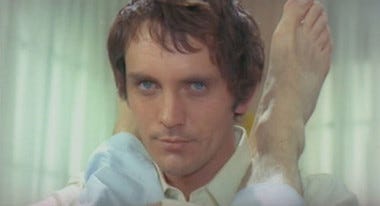

While Spectacle now decorates the serial killer with the benefit of Method, it is the Herostratian terrorist who has κόσμος. He is destruction-as-creator. Whether he is as unassumingly subversive as Descartes or as seductive as Terence Stamp in Teorema, for his act to be effective and for it to―maybe, with luck―ripple through collective, folk, historic or genetic memory, it must be unrepeatable and unforgettable. Therein his nod to Spectacle: the Herostratian knows that, even more than beauty, terror has aura. Terror is non-fungible.

Two days ago [on July 19, 2020] social media was ablaze with reports of “baby witches” hexing the Moon. The implications of targeting not only Artemis, again, but the Thing-In-Itself, fall within the scope of the occult and even of the philosophical. What they are not is: artistic, historic, or spectacular. As an attempted attack on the gods, this hexing of the Moon was borne not from a terminal knowledge, but from a misconception of the means and purpose of divine assault so thorough as to render any deicidal effort—no matter how organised—completely futile.

Only the sovereign slips through the law.

Still of Terence Stamp in Pier Paolo Pasolini’s Teorema, 1968.