First version published @ Ribbonfarm on July 07, 2020.

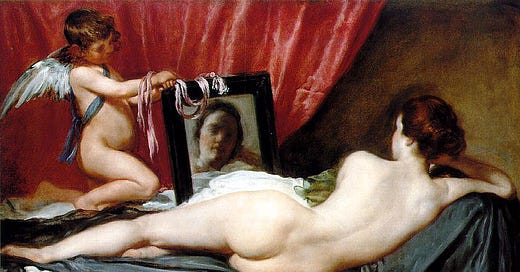

Velázquez’s Venus may be the most naked on record: with no-one but her lovechild, Cupid, to hold up a mirror to her difuse reflection (deflection?), she lacks most of the mythic giveaways of her traditional representations. She is unlandscaped, unjewelled, unmyrtled. She can’t be [M]arsed. If not for the luxuriant fabrics she is recumbent on, or for that fleshy tongue of curtain, her room is as featureless as Cupid’s left leg, which is as faded as her visage. Seen glancingly, she is the picture of a modern, mortal woman: an adaptation that, to some extent, accounts for her survival into our time.

An icon in a history of iconoclasm, she first materialised within the private chambers of Felipe IV to join two other mirror-bearing Venuses by Titian and Rubens. Though female nudes were rare and heavily policed in the Baroque Spanish court, Velázquez―as court painter―was no less heavily protected; his Venus so admired by the king and his validos they screened her from hazard and censors.

This Venus is not self-absorbed, but considerate of the efforts expended to preserve her. She shows us her backside but not her pudendum, unlike her more brazen revision as Goya’s Nude Maja. Her gaze is averted from the viewer’s, but complicit with the painter’s: a tour de force on power mechanics and triangulation. By hook and by crook, she eventually made it to England, where she was granted her Rokeby title and earned the devotion of another king, Edward VII, who secured her sinecure at London’s National Gallery.

In Art and Illusion, E. H. Gombrich has Matisse rebutting criticism on the proportions of one of his portraits by saying: “This is not a woman, this is a painting.” The Rokeby Venus is neither.

In 1914, Mary Richardson, a British suffragette out for symbolic blood, took a meat cleaver to Venus, slashing her seven times from neck to rump. She was incensed by the painting’s allure, and claimed she meant to “destroy the picture of the most beautiful woman in mythological history” to protest the arrest of Emmeline Pankhurst, “the most beautiful character in modern history.”

A fascinating precedent in activist idolatry, it contains the unexamined kernel of Ms. Richardson’s remarkable instinct against the aphrodisiac.

Plato’s Symposium comments on two versions of the birth of Aphrodite: the glorious one of Hesiod’s Theogony, where she sprang from the foam of Uranus’ jettisoned genitals; and the one in the Illiad, where she is the daughter of Zeus and Dione—injured by Diomedes’ spear. This is the goddess aspect Ms. Richardson stabbed, and why she ultimately failed as a deicide.

If the fullformed, sexually indifferent beauty Botticelli captured in his famous painting corresponds to the transcendent Aphrodite Ourania, the entity Ms. Richardson assaulted hews more closely to Aphrodite Pandemos, who held court in the agora and was “of all [the] people.” As such, she encompassed—but also exceeded—her terrorist’s cause. Ms. Richardson both hit and missed by targeting the aphrodisiac as grand unifying principle.

Befitting her nature and stature, the goddess was restored completely. In addition to spending six months in prison―the maximum sentence for defacing a work of art―Ms. Richardson deserves to be commemorated as an early model for a very different mirroring of womankind: the feminist as frenemy and foil to the eternal feminine.

Diego Velázquez. Rokeby Venus, c. 1647–51. 122 × 177 cm. National Gallery, London.

The Ecstasy of Saint Emmeline, being arrested outside Buckingham Palace whilst attempting to deliver a petition to King George V on 21 May, 1914. Photographer unknown. Image created and released by the Imperial War Museum on the IWM Non Commercial Licence.