The New Vertigo [annotated]

Notes on Covid’s tricksterism and the limits of our age’s imagination

First version published @ LapsusLima on April 9, 2020.

The exponential of panic is vertigo. Amp it to a global and collective high—a singularity of historical communion—and it will soon take on the rattle of the orgy or the charnelhouse. Which way indeed, Western man.

Our pandemic is distinguished by its multiscalar magnitude, its networked narrativisation, and a sense of being persistently contemporaneous: everything is happening at once in the world-historical bat-of-an-eye.

It would be easy to brand and bag this whole period as “liminal,” but a nine-month long free-fall is no more liminal than spaghettification. Based on its destruction of routine and ritual, this is a phase-shift, not an initiation. There is nowhere to go [back] to. The only way forward is through.

So it makes sense that the leitmotif of Wave One was the unprecedented. In having no remembered past and no sufficient future, the unprecedented is a time-out-of-mindfuck that is at once original and ever-present, first and only; ripe for revelation and—as we will come to see—resistant to representation.

In a very Augustinian sense, our ability to connect with “reality”—to ground ourselves—now depends on our capacity to be attentive in the moment, and able to move from moment to moment like squirrels on a limb. The alternative is the loss of grounding, gravity and orientation in the total virtual. (Hence, aesthetics as an early warning system. If you feel it, think about it).

It is telling how, despite our networked immersion, Covid’s visual record remains nouminously poor, but viscerally felt (especially in the early days).

It’s as if we held only outlines of the images associated with Covid—from hospital staff wearing garbage bags as PPE and streams of patients hooked on ventilators, to mass graves in Hart Island, bodies being incinerated on the streets of Guayaquil, and so forth. There’s an artful misdirection in how these pictures draw attention not to the disease—“Nothing to see here!”—but towards our failure to contain and manage it.

In a world of sped-up simulacra, Covid wins by lacking spectacle. It isn’t Ebola, no—the Thing-in-Itself is cloaked and daggered, masked and here to unmask us. It releases enough hostages to come across as tractable, but still it will not let us hold a proper funeral (once again, disrupting ritual).

Covid’s reflections and deflections—its mirroring effects and cryptic camouflage—are something I hope to revisit, often and soon [1]. They are the reason I opted to approach this project sideways, like Perseus did Medusa, through bracketing (epoché) or the “suspension of trust in the objectivity of the world.” [2] They are the keystone to #Hyperbaroque. More importantly, they may account for how mass socially siloed vertigo emerged as a central Covidian affect.

Before this, we could have readily imagined similar vertiginous sensations overcoming discrete human groups—families, tribes, certainly nations. But nothing as life-bending as Covid had crept into every nook of the inhabited world before, or had its consequences visited on all of us, at once, on such a scale. [3]

Nor is this the vertigo of claustrophobia. Humans have two basic, distinct and [indi]sociable drives: crowding and belonging. With protracted lockdowns keeping them both in check—as the urge for each continues to exacerbate the craving for the other—Covidian vertigo is an agoraphile, compersive and explosive, eager to reach-through and reach-around.

Aesthetically, this uncurbed vertigo and its accelerations do not correspond to the uncanny—with its hidden, homely, heimlich connotations—but to the prodigious: that which is nothing other than, to come full circle, unprecedented.

In the first iteration of this article, I expressed surprise at seeing no uptick in five-legged calfs and two-headed snakes, though I anticipated that we would soon.

That was then. We’ve since experienced everything from a resurgence in Loch Ness Monster sightings to something fringing on disclosure to apocalyptic, record-breaking wildfire skies glow[er]ing over California. Nothing, however, has captivated the Covidian imagination so much as its limitations.

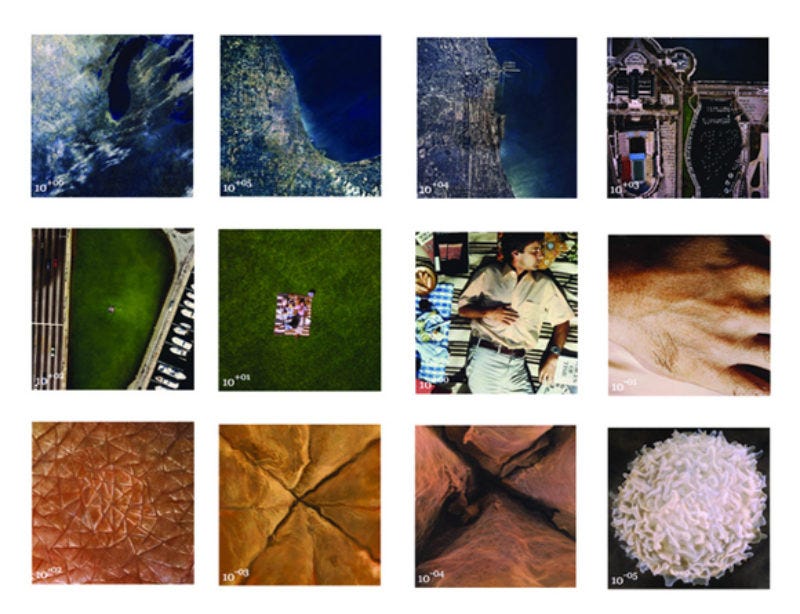

Stills from Charles and Ray Eames’ Powers of Ten: A Film Dealing with the Relative Size of Things in the Universe and the Effect of Adding Another Zero (1977).

NOTE

[1] I submit this tweet from June as early evidence of noting Covid’s tricksterism. This aspect of the virus was first brought to my attention by Dr. André Watson, who was kind enough to let our conversation turn into an interview on/of Covid.

[2] Gabriella Farina (2014). “Some Reflections on the Phenomenological Method.” Rome: Dialogues in Philosophy, Mental and Neuro Sciences, 7(2):50–62.

[3] As noted in April, Covidian potential for social-behavioural reorientations was immediately apparent, within an optimistically limited window of maybe two years—now reduced, as a vaccine evolves from possible to plausible. Another lens through which to look upon our time and tremble.