i

If there’s one constant in online culture, it’s the fascination with categorising people.

It’s very old news that people like to categorize themselves. What’s my sign? What’s my Myers-Briggs type? What’s my Enneagram? What’s my D&D alignment? Which of these colors, which of these categories, am I? It’s not like these systems are useful predictors of anything. Myers-Briggs is about as reproducible as the luminiferous aether, and yet it carries massive cultural cachet: everyone reading this knows what an “introvert” is.

We do this with other people, too. When we want to, say, complain about an annoying interpersonal situation in our lives, notice the form that we reach for: rather than talk about a certain annoying action that people might do, we are inclined to describe the person who performs that action. Similarly, if we want to express sympathy for such a situation, we might say: “oh, yeah, I know someone like that.” Some of these Types of Guy are sticky enough to embed themselves into the popular consciousness.

There are the stock characters of the Very Online: the incel, the Chad, the Stacy, the e-girl, the simp, the girlboss, etc. And even those who aren’t addicted to Twitter memes are getting in on the action. The term “incel” has been plucked from the Very Online cosmology, and is now in regular use describing actual people in newspaper headlines. The “nice guy,” the “softboy,” and the “pick-me girl” have all been the subject of instructional Buzzfeed articles, Facebook diagrams, and Instagram infographics. It’s not surprising, then, that we also try to address our social ills with ontologies of Types of Guy: 17 types of male “feminists” that need to be stopped; 4 kinds of racists: which one are you, and so on.

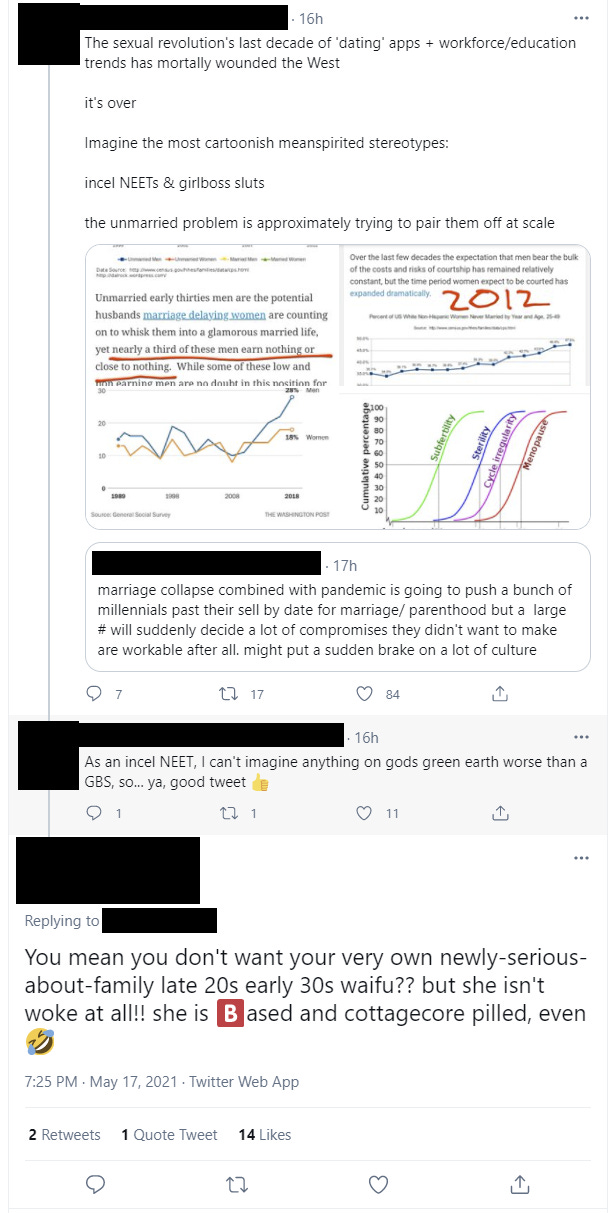

On its own, this instinct is harmless, but sometimes people take these archetypes and run so far with them, they end up off the playing field. Here’s a particularly spicy example of what I mean:

I dearly hope our anonymous friends here have their tongues more in their cheeks than not (although I’m not quite sure). Regardless, I hope you recognize this class of error. Internet stock characters aren’t like anyone I actually know, or even anyone I’ve ever met; but it’s tempting to begin to treat them, explicitly or implicitly, as if they really exist and represent significant demographic forces.

I would like to talk about why this happens.

ii

Stock characters in the West have been around since ancient Greece—Plautus’ Miles Gloriosus (Braggart Soldier), no brains and all vanity, was based on a Greek stereotype—but recently, we’re more likely to trace the lineage back to the early-modern Italian commedia dell’arte. In the commedia, each performer dons a mask (or at least elaborate make-up) to take on a particular rote role. Arlecchino, or Harlequin, the crafty servant, is probably the most famous of these characters today; each of them, in any case, plays to a handful of defining characteristics.

In his work on the commedia, John Rutlin writes:

“In commedia dell’arte the isolation of, say, avarice in Pantalone or of intellectual pretension in Il Dottore, is completely crystallised in their masks. As an actor you must work within the limitations of the persona and cannot escape into the complexities of personality. In a sense you are the prisoner of the mask, and you must play out your part in terms of the statement it makes, rather than in terms of some complex of emotions that go beyond that statement. Actors must ‘live up’ to the mask. As soon as they can no longer do so, either because society no longer finds it relevant or because the arte which sustains it is in decay (as it was in Goldoni’s time), they must surrender creative autonomy to the writer in order to continue to earn a living.

Each mask represents a moment in everyone’s (rather than someone’s) life.

Familiar in many ways. And yet, not.

Insofar as written fiction dominates our culture, we’ve demanded more and more interiority in our pop-cultural figures. If anyone could live in the realm of the archetypal, you’d think it would be superheroes, and yet every hero in the MCU gets their own detailed origin story and character arc. It’s not enough to have Iron Man flying around as a billionaire trickster playboy; he needs to grow, change, mature.

In commedia, by contrast, the characters are emphatically static. There is no interest in psychologising the individual; the actor is supposed to be subsumed into the mask, and the psychology of the mask is not the heart of it, either. We can read the description of every mask and not really get why anyone would care about this stuff. The fundamental unit of commedia, if there is one, arises only in action between the players, and between the players and the audience. The fundamental direction of commedia is not to plumb the depths of the characters’ psyches for greater “growth” or “explanation,” which assumes several ideas: that our behavior can be regarded as a mechanism, and that to find a few more gears in that mechanism constitutes a significant discovery, and that this kind of discovery is the important thing to do. Commedia finds enough to do in its own way.

Note, also, that last point: “Each mask represents a moment in everyone’s (rather than someone’s) life.” This might seem counterintuitive, since many of the masks are distinctly poor servants, and many are, distinctly, upper-class and wealthy. So necessarily, any audience member would be of a different social standing than a number of the characters. But this statement makes sense when we see the masks not as “representing” different segments of the audience, but as instruments used to evoke emotions, dynamics, and contrasts between the characters that might speak to anyone.

iii

So that’s the thing with archetypes and stereotypes. When we use them to evoke different social experiences or observations (e.g. the experience of being condescended to, or the experience of being humiliated), they speak to us. Conversely, when we drag them out of that world, and use them as discrete dolls or pieces of data that we mash together to “do sociology,” we start building castles in the sky. We make models of society based on the motivations of entirely imaginary actors, which we then stretch and squeeze grotesquely to correspond with whatever supporting data we’ve latched onto.

Social media has made us more dependent on communication through text than any generation before. It’s not surprising, then, that it has a troubled relationship with masks, archetypes and stereotypes. As Rutlin describes, the commedia is a kind of resistance to the detailed scripting of scenarios that, inevitably, require writing. And, conversely, the technology of writing resists archetypes and stereotypes, and reaches toward detail-oriented characterization; words on a page (or a screen) are produced in a different way, and face a different kind of scrutiny, than improvised live performance. In a writers’ world, stock characters are out of place.

But that doesn’t mean they’ve lost their power. In his book on the commedia, intended as instruction for a beginning actor, Rutlin insists on treating the mask with care and respect. He quotes French actor and director Charles Dullin:

A mask has its own life…Nothing annoys me more than to see a student leap upon it like a draper’s assistant grabbing a carnival mask. I feel that he commits a sacrilegious act, for in fact the mask has a sacred character.

It may sound superstitious, but I don’t think Dullin is wrong to respect the compelling power of the mask. It is when we slip into using these masks as yardsticks—when we start to mix up the stock characters with humans—that we start to go crazy.

Anonymous. Capitan Babbeo e Cucuba. 18th century. Scala Archives, Carnevale Collection.

Neil Fitzgerald is interested in how stories and art interact with human understanding. You can follow him, DM him, and/or find his other writing @antilegible.