First version published @ LapsusLima on April 11, 2020.

The more I ponder the Covidian, the more I realise I have the Early Modern Era, and the seventeenth century notably, as my sounding board.

The Baroque—and its dyadic counterpart, the Renaissance—was one of two beta versions of modernity, the templates for which crossed like [s]words in the Enlightenment. The two were contrapuntal machinations of the German Romantic Geist cresting with Nietzsche’s rediscovery of Greece. After all, the Gesamtkunstwerk of the Philologists, their great philosophical merit, was the invention of History as an aesthetic.

In this scheme, the Baroque is what takes shape in the shadows; an about-face to the Renaissance and a preface to the Enlightenment.

In alignment with our essay on The New Vertigo, the Baroque is also epoché, suspension, up-in-the-air, a surface of the Floating World, and so it may be useful to think of it as being governed not so much by dialectics and argumentation than through narrative, contrivance, apparition and agglomeration. We are trapped in an immersive mystery-play staged for the benefit of the Great Theatre of the World; in Kraus’ Last Days of Mankind captured through a cracked, gilded écran.

The disdain for detail that Burkhardt thought of as characteristically Baroque is not unlike the noise produced by our own, intensely granular refluxes of information, reification and disinformation. There’s a natively misleading quality to the Baroque that registers not with the slickness of lies but with an almost televisual fuzz, riddled with insinuation.

The Baroque is a hairline fracture in modern historical world processes. It is thus a feature of the fold: less a Period than a Moment; a chimeric-atmospheric beast of epochs wrought from the forge—and through the forgery—of emergent and intercolliding properties, of missing but constitutively implicated pieces. Euripidean drama, Mennippean satire, Spenglerian historiography—maybe postmodernism, even—are all Baroque in this sense, or merit at least Baroque scrutiny.

The Baroque is also visionary and apocalyptic—a mise en scène, or abyme, with a need for revelation via masking or unmasking as its telos—which may be why I found myself drawing connections between the Covidian moment, the pharmakos in plague-stricken Marsilia, and the mass hysteria events that swept through the seventeenth century at Aix en Provence (1611), Pendle (1612), Loudon (1634) and even Salem (1692), in the colonies.

But more on this tomorrow, whenever that may be.

Still from Ken Russell’s The Devils, 1971.

NOTES

This text was expanded, made more precise and supplemented by the ulterior “Hyperbaroque,” but it was part of the train of thought that led me to realise that our variety of Baroque experience was not like any of its subcategories—Rococo, Plateresque or Churrigueresque (aka Ultra Baroque)—but a new turn of the screw.

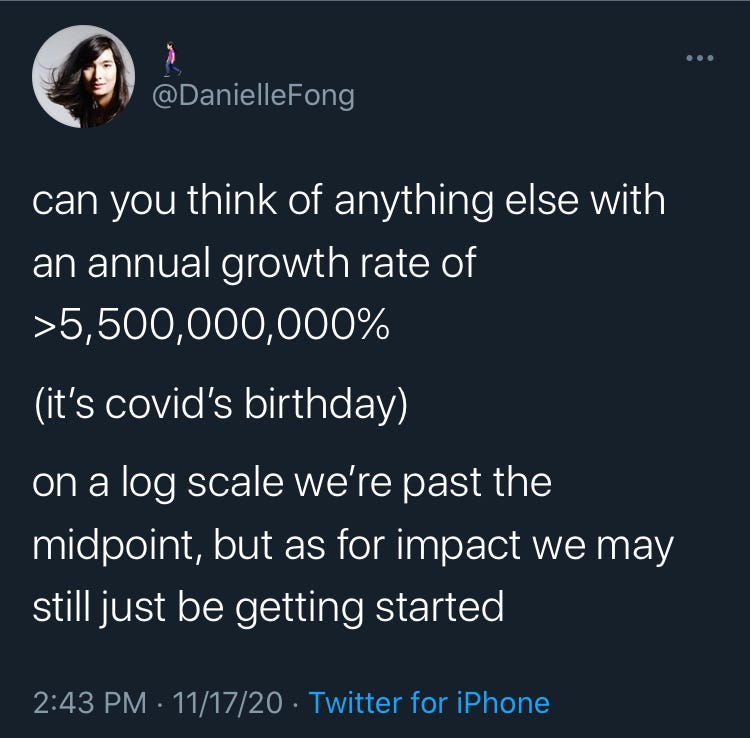

The fundamental differences are in emphasis, substance and scale: if the Baroque is movement (cfr Maravall), the Hyperbaroque is acceleration. And as we have witnessed, the escape velocity of movement is exposure to the exponential; which we’re ill-equipped to grasp, much less handle.

(Humankind cannot take very much reality, because our tolerance and hankering for hyperreality is bottomless).

In the words of Danielle Fong, today—November 17th, on Covid’s birthday: