There will be no more superstars; no more Sammy Davis Jrs. or Madonnas or even Pitbulls because the internet killed the media infrastructure that made superstardom possible. Billie Eilish is probably the last gasp of the old media factory and even then, her tried and true shtick—the teen-starlet-to-Vegas-residency arc—has to kick up its pace to keep the Eilish image trending.

The Grammy Awards are another sign. Audience ratings for such stuff have trended downward since the mid-2000’s, but with so many Americans stuck at home, you might think the Covidian Grammys would have seen an uptick. What better comfort during a pandemic than to gather around the warm glow of a television to celebrate our nation’s shared musical talent? But no, the Grammys hit an all-time ratings slump this year: about 9 million viewers. For comparison, 20 million viewers tune in for football games and sitcoms.

The day after the show, a Chicago Tribune article registered its confusion about the poor attendance, remarking in all earnestness that “the primetime ceremony had an impressive lineup featuring over 22 musicians, including Bad Bunny, Black Pumas, Cardi B, Brandi Carlile, Mickey Guyton, Haim, Brittany Howard, Miranda Lambert, Lil Baby, Chris Martin, John Mayer, Maren Morris and Roddy Rich.”

Why didn’t people tune in? An enigma! The Chicago Tribune believes this lineup should have dragged America away from Instagram and YouTube for three hours. I recognize a few names—the ones anyone over thirty would recognize from a decade ago. But as the stars of John Mayer and Miranda Lambert flicker out, the new stars rising are still pretty dim. Who is Maren Morris? What is a “Haim”?

The highest rated Grammy Awards were broadcast in 1984 and 2012 (maybe the Mayans were right about history coming to an end that year). 50 million viewers and 40 million viewers, respectively, tuned in those years, which featured performers and nominees like Michael Jackson, B. B. King, Sting, Donna Summer, Bruce Springsteen, Alicia Keys, Taylor Swift, Katy Perry, Foo Fighters, Blake Shelton.

Lest I be accused of “old man yells at cloud,” let me point out that I’m not interested in taste or sales or kids these days. What has changed between Springsteen and Haim—and what I’m trying to point out here—is the ambient media environment’s ability to manufacture stardom. When it comes to Michael Jackson or Bruce Springsteen, I do not need to have heard these artists to have heard of them. I don’t even need to like them. I purposefully avoid Taylor Swift. I couldn’t name a single song by Donna Summer. But I do know their names. My parents never listened to Nirvana (“Keep that crap on your Walkman!”), but even in the early 2000s, they’d heard of Nirvana. This is an effect of the media environment, not the content.

Today, unless you listen to Haim or Lil Baby or Maren Morris, you’ve probably never heard of these acts. That, too, is an effect of media environment, not content. I am sure that Brittany Howard, whoever she is, is very good at whatever it is she does.

Andy Warhol envisioned a future in which everyone would be famous for fifteen minutes. In The Gondoliers, Gilbert and Sullivan told us what that future would look like: “When everybody’s somebody, then no one’s anybody!” This is our era, the age of the microcelebrity, when the best starry-eyed artists can hope for is 5 million casual regional followers instead of 500 million dedicated fans across the globe.

Don’t confuse this new phenomenon with the traditional one hit wonder (or homo unius libri, the man of one book, to use the Latin phrase). More people can sing “Funkytown” or dance the Macarena than can name a Mickey Guyton song. Microcelebrity is something different. It’s the kind of stardom available—the only kind of stardom available—to artists in a society that has fragmented, networked, and echochambered itself into hyper-curated media bubbles; which is just theory jargon to describe the world we inhabit: the world of smart phones, constant internet, and virtual communities dedicated to ancient steppe lore, competitive vodka-tasting, and knitted hats for pet chameleons.

Microcelebrity exists in direct proportion to the disappearance of superstardom, and the internet killed superstardom by killing, not so much the old media empires, as their ability to provide shared media. In the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, a limited number of printing presses, a limited number of film and recording studios, a limited number of television channels, and a limited number of places to showcase art produced a media monoculture (to borrow a phrase from Paul Skallas). But America, the West, the entire globe, none of us share media in the pandemic age the way we did fifty, thirty, or even ten years ago.

It is a truism, but when there are only five channels on television, we all watch the same thing. When there are only a dozen record companies, we listen to the same artists (or, at least, we have heard of the same artists). This is the media milieu that produces shared media, the monoculture; and shared media is what produces superstars. This is the media environment where a kid who speaks no English still knows the line “Here’s looking at you, kid.” This is the media environment that allowed Steven Spielberg, in Munich, to portray a group of international militants listening to Marvin Gaye, because Gaye is the neutral music option both Palestinians and the Red Army Faction could enjoy.

Somewhere between 2010 and Covid, the fragmented internet culture superseded this old media monoculture. It had been slowly disintegrating before Covid, sure enough, so it’s hard to pinpoint an exact timeline. Perhaps September 11th was the last truly shared media event of the new millennium. (Personally, I think the smartphone is more to blame than the internet itself. I’d put the watershed around 2012, when smartphones started to gain traction. The damn Mayans again!)

A media delivery system in everyone’s pocket turned out to be the crucial weapon against monoculture. Once everyone had instant 24/7 access, content proliferated into quantities so vast that “shared media” became an obsolete experience, at least at a cultural scale. The kids today share memes in small groups. They do not share media. Shared media was the privilege of the twentieth century.

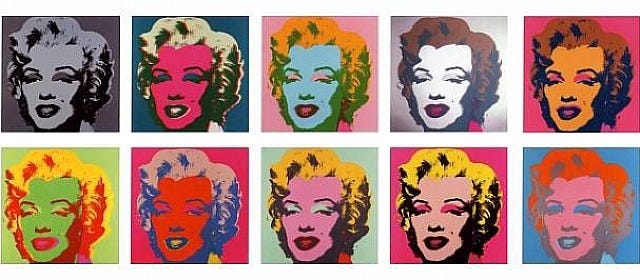

The pandemic has only solidified the fact that all content is niche content, that all media is now curated into customised habits rather than experienced as cultural events or common happenings. Audiences form their own worlds of art, culture, and celebrity without anyone else on the planet noticing or caring. It doesn’t matter if these niche worlds are comprised of fifty or five million people; compared to the global stage inhabited by Marilyn Monroe and Michael Jackson, the new stages are just Islands of Lilliput inhabited by microcelebrities.

The old monoculture could produce a Marilyn. Today, the best it can do is—Bad Bunny.

Andy Warhol. Marilyn Monroe (Portfolio of 10. The complete set of ten screenprints in colors). 1967. Prints and multiples, screenprint on paper. 36 x 36 in. (91.4 x 91.4 cm).

Seth Largo is a climber, English professor, and author of Excavating the Memory Palace: Arts of Visualization from the Agora to the Computer (University of Chicago Press, 2020).

A good use of image in this very interesting piece. You put it well: no more superstars as its more about customized niche markets. Has the digital accelerated neoliberalism so it is pervasive in media. Culture no longer experienced as an event. Art not as a hammer or even a mirror really.