First published @ Ribbonfarm on September 2, 2020.

To picture a rhinoceros in Renaissance Portugal, consider the unicorn. Whether conflated with the oryx or the narwhal at its southernmost and northernmost coordinates, the unicorn was no less of a shapeshifter than Dionysus, who came from the East―the two sharing goatlike renditions; the axis, as Pliny described it, being “sacred to Bacchus.”

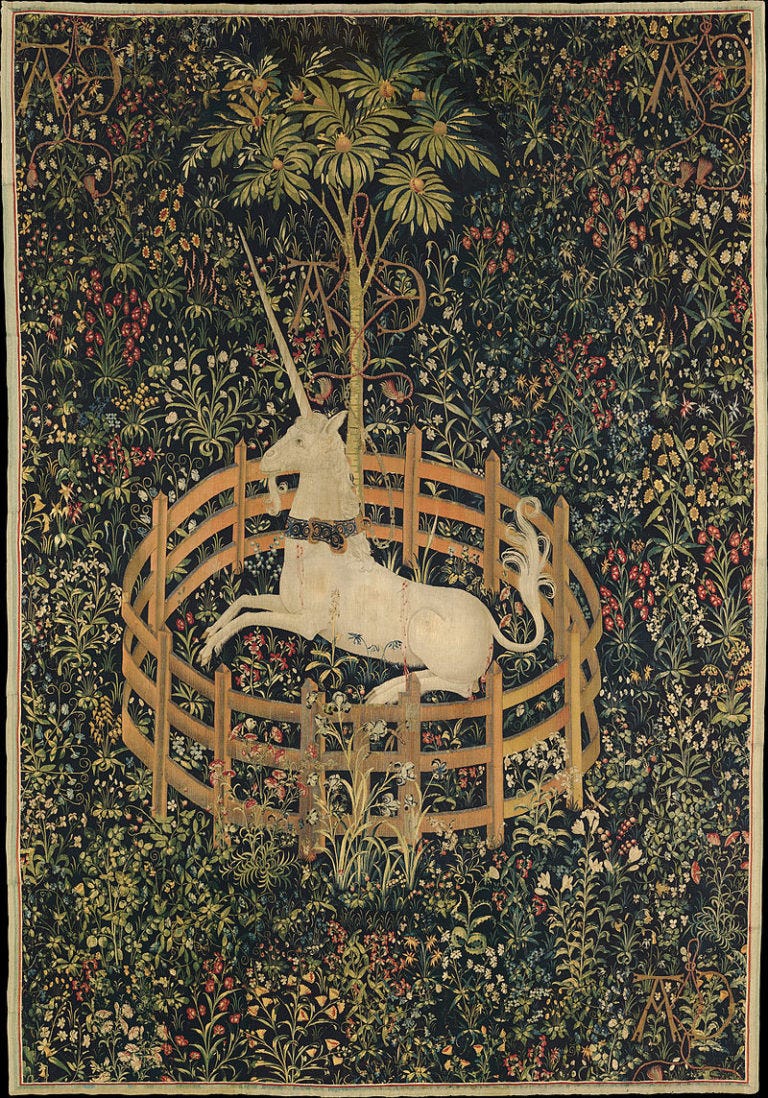

The unicorn began its westward march during the Bronze Age, from the Indus Valley; its virtuous, convertible version as horned horse―beguiled and betrayed by a virgin―anchored in Late Antiquity by the Physiologus. The hunt of the unicorn established itself as a Christian allegory, laced with barely suppressed panic menace, through the Middle Ages. Save for a handful of scholars who insisted on the identity of both creatures, the rhinoceros was all but lost to Western memory.

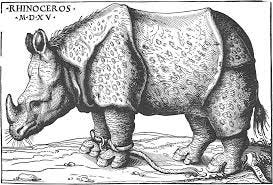

Until 1515, there had been no rhinos in Europe since Roman times, when great exotics―animal and human―were consumed as entertainment. The Indian exemplar that arrived in Lisbon from Goa as a diplomatic gift to King Manuel I―and which drowned while being transported in the same capacity to Pope Leo X―was a time-traveller, an alien visitor, a royal hostage. It was beheld by two kings, examined by experts, dispersed by correspondents and inspired a curious woodcut as accompaniment to a self-effacing poemetto by a doctor Penni, whose claim to historical fame was to witness the beast.

A letter describing the rhino and a[nother] sketch of it wound their way to Nuremberg, where Albrecht Dürer took what best he could from them―and Pliny―to show accuracy is accessory to success. His was not the first impression of the creature, nor―unlike Hans Burgkmair’s coeval woodcut―was his accurate, but Dürer’s rhino was too real for reality to outcompete. Despite the reintroduction of rhinoceroses to Portuguese and Spanish courts in 1577―and their sporadic appearance in art, under sometimes very illustrious names, yet earlier―Dürer’s rhino served as his species’ ambassador to Europe until the Enlightenment.

The genius of Dürer’s rhino is partially encoded in its hyperreality. As it slouched westward over centuries, it became recognisable―in its resemblance to the concept of a rhino, and in its deviance from it. Scholarly discussion of its skin abounds, with some opinions pointing to it not being hide, but hidden, armoured. After Pliny, King Manuel did try to make his beast combat one of his elephants, and the rhino’s portrait may include its cover as eventual automaton, test subject, neural link, cyborg. Unlike Burgkmair’s rhino, Dürer’s is also unchained, suggesting its identity as unicorn, the animal that can’t be captured lest it be through virgin eyes―like Dürer’s were. We may not have such eyes again.

Albrecht Dürer. The Rhinoceros. 1515. Woodcut. 23.5 cm × 29.8 cm. National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C.

Anonymous. The Unicorn is in Captivity and No Longer Dead. 1495-1505. One of seven tapestries popularly known as the Unicorn Tapestries or the Hunt of the Unicorn. Wool, silk, silver, and gilt. The Cloisters, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York.

Frontispiece of Giovanni Giacomo Penni’s Forma & Natura & Costumi de lo Rinocerothe stato condutto importogallo dal Capitanio de larmata del Re & altre belle cose condutte dalle insule nouamente trouate. 1515. 10 cm × 9,5 cm. Institución Colombina, Seville.

Burgkmair, Hans. The Rhinoceros. 1515. Woodcut.