A bout of labyrinthitis years ago once gave me the impression of seeing the world through a frame: not because my vision was affected, but because my ability to walk or function standing or sitting up was dependent on keeping my head straight and still, looking forward only. I had to step on and off of trains looking ahead and not down, and if someone entered my office, I would have to turn my entire body in the chair to speak to them, constraining the innumerable micro-movements we perform under normal circumstances. The result was a world that seemed somehow false, in stop-motion rather than fluid, but all the more chaotic for the minutiae of its control. Here, at the water’s edge, I realised the feeling that had followed me from the moment I entered the continent was that of being a character in a movie, aware that my life was only within the frame of the image and not without, whatever actions I performed provided as direction somewhere on a page.

In Francis Bacon’s Triptych August 1972, the artist and his lover George Dyer, seated, flank the central panel in which they are combined in a sexual topology described by the Tate Museum’s website as “a life-and-death struggle” where, according to Bacon’s biographer, “what death has not already consumed seeps incontinently out of the figures as their shadows.” The observer observes but is also observed; it was both paranoid and natural that I should wonder who was watching me. Death had not consumed me, true, but then I had spent a lifetime in its company. My ragged breath was my shadow, and the three of us had made our way through the thickness of time, slow in our phlegmatic persistence. We now found ourselves in the unknown world “set against black voids”, although here they were neither Bacon’s darkness nor Klein’s white, but Canaletto’s impure aquamarine.

As the taxi pulled into the quiet, unhurried traffic of the main waterway, I looked out with the same sense of visual overload I had had in that Bavarian hotel. It was too much: the shuttered palazzos lining each side of the Grand Canal, the striped pali da casada, the flocks of black-crested gondolas moored, like great primeval nesting birds. Brodsky’s line about traveling by water being almost primordial came to mind. Passing under the Rialto bridge—overhung with some, but not many, people—then turning closely into smaller canals to see the tops of cloistered gardens, branches of pomegranate trees with their golden-red fruit arching gracefully over old walls like arms seeking an escape: the seeds of illness we had eaten, and who knew how many more months to go despite this, the briefest of respites.

Writing about The Cantos in “Persephone’s Ezra”, Guy Davenport refers to “the force that reclaims lost form, lost spirit, Persephone’s transformation back to virginity.” It was hard to believe at that moment that there was any sort of force—disbelief, signs, or otherwise—that could restore our metaphorical virginity (a delusion to start with), let alone our actual, collective health. People went about their daily business, with small dogs on leads, chic briefcases, or grocery bags in hand. Almost all were masked but walked and interacted with everyday ease, devoid of the tension that I had experienced for months. Turning back to the expanse of water, I watched the rhythm of the little waves, breathing in and out as they rose and fell, at times feeling a fine mist on my face. The motor of the boat hummed in the background; another kind of nebuliser. To breathe again was too much, and not nearly enough.

A gondola with passengers moved towards us from the opposite direction. This was to be a rare sighting, and if I have described the numerous moored boats as nesting birds, then this was as wondrous as seeing one in flight. Two women sat inside: preening, adjusting and readjusting a phone in order to take a selfie rather than looking out onto the strange new city. Part of me wondered if this was all normal to them; that in the relative emptiness—and perhaps they did not even register either the lack of people or the air of change—they were the natural focus of everything. It had long seemed to me that people had shifted their perspective to frame themselves as I had so uncomfortably felt before, as if in a movie or by becoming the axis on which the world turned.

The last time I had been in Paris, at the Louvre, I watched a man stand with his back turned to Géricault’s The Raft of the Medusa, smiling broadly as he snapped his own picture. Against the death and madness, confusion and hopeless resignation of the painting’s faces, he laughed and gesticulated, a historical event rendered in sickening detail from the testimony of survivors and studies of remains reduced to a momentary distraction. His eyes searched out the next violent painting like the people in the car-crash scene from Godard’s Weekend: the carnage beside them signifying nothing more than entertainment—a tableau vivant, more unreal than real—, a reminder that interest is now fleeting if it fails to involve and indulge the self.

This could also be said to be unconsciously—though that may be too generous—a means of sheltering oneself from the world. Protection has an element of ignorance, or more liberally, naiveté. But how far we have reverted from the imaginary real of the lamassu!—the belief that nothing bad can happen to one, or a disbelief of harm. To centre oneself in the face of despair and chaos; the hubris of declaring oneself beyond what affects others. The camera phone becomes the agent of this cinematic narrative, where one is guaranteed a happy ending—or at least survival—as the central character. The difference was that, while I was paranoid of the unseen audience’s reception outside of my imaginary frame, I realised others assumed greatness, and that to them this was altogether natural. It was true that I feared the unknown of this new time, but nor did I want to shut it out. As the gondola swept on, I thought what a fitting amulet it was for the age, this device that allowed one to create a world where it was possible to always be its centre while remaining detached from it.

In Paolo Sorrentino’s The New Pope, the former Pope, played by Jude Law, lies in a coma in a Venetian hospital, having fallen unconscious after delivering a speech in St Mark’s Square. In almost every way, he is given up for dead; except for that the young Pope is already thought of as a living saint, so a sign of some sort to his followers is inevitable, expected. Sure enough, the nun on night watch by his bedside reports after some time that his breathing is miraculously forming a pattern: after x amount of breaths, he sighs once in the depths of his sleep. Each time she has counted, there is one less breath before the next and so, to the crowds of his devotees, who camp day and night outside his window, this is their revelation; that only they knew was coming but could not calculate or articulate beyond the amorphousness of belief, finally given the correct-shaped hole to fit the object of their faith in.

And the Pope—who occupied that liminal unknown between life and death—does wake as the breaths foretold, and in his waking he returns with the foresight that allows him to see past, present, and future. In a kind of divine modesty, he leaves people to continue to attempt to interpret the signs of the world as best as their mortal blindness allows. I have mentioned before the achronology of signs and how they nevertheless find us and fit our narratives. I did not see this series, nor had any idea what it was about, until months after I had returned—and so I watched with a sort of disbelief at first. As the Pope breathed, the city held its breath. As the world held its breath, Venice, for a while, breathed and sighed in its sleep.

To not be a Venetian and to wake in Venice is a curious thing; during the entirety of my stay, every time I woke—whether in the morning or the middle of the night—it felt as if I was entering another dream. This is less romantic than it is prosaic: staying in an apartment on the Campo Santa Fosca directly overlooking a canal, the sound of water is the first thing I would hear in my hypnagogic state. It had the effect of falling asleep, then waking, in a bath, or what it used to be like to sleep, unaccustomed, on a waterbed—for a few moments one does not realise where one is or how one got there, the humid scent of water lapping at one’s dreams. But I also do not personally know any Venetians, and it might also be true that they, too, sleep and wake to the sound of water as if they were permanently in a dream. (I did, however, watch a dog in an apartment across the water from me every day—hanging its head outside of the window, the rapt look on its face and the wag of its tail were enough to convince me this dream state extended at least to the local pets). This lack of boundary considered in itself is romantic, because it makes one think of life lived as a constant journey, despite being fixed to a place. To go as one does in Venice, from this aqueous limen into the city itself, made of up such a labyrinth of streets, reminded me of lungs again; its narrow, many passages as bronchi and bronchioles, of openings and discovery, and most of all, of what it is to breathe.

It would come as no real surprise then, least of all to myself, that once I started to walk in the city, I found my breathing mirroring its shapes: in the squares and wider streets, it came and went with a luxuriant ease born of forgetting, the relative emptiness contributing to a—false or otherwise—sense of freedom. Then there was also an impression of emotional displacement, as in the large, near-empty corner by the main gate of the Arsenale where, for a while, the streets are broad, waiting for footfall that has not—and will not—come. The shadows falling on the pavements—bright faded white of the pride of stone lions, dark-green shuttered arches—made me think whatever I was feeling would only make itself known if I stopped looking directly at them, but through that strange frame instead. Here my breath was metronomic, a measured and precise uncanniness where the shutters might have opened and closed, the shadows withdrawn and closed-in, in rhythm; with only the still lions watching the landscape from within a time of their own, where past and present looped as if played on some great cosmic reel.

In the narrower passages off of the main thoroughfares or in the less intruded districts, I could feel my breath tighten; sometimes seized by a respiratory claustrophobia that those old deniers of my condition would point to, in triumph, as a proof that it was all in my head. At others, in a kind of empathy with the city’s urban planning and architecture, the longing to sigh at its beauty was stopped short by an indescribable presentiment of loss, as if breathing of any kind would take away from what surrounded me: the cherubic or sometimes grotesque open-mouthed waterspouts on the sides of buildings; sleeping cats piled atop each other in baskets and boxes on ledges in neighbourhoods of almost impermeable quiet, slandered in old tales as stealers of breath. Most of all, the bending pomegranate trees that were everywhere, their melancholy gesture making even the curving prongs of their crowned fruit appear like open, wailing mouths.

To look at certain buildings is to note their own kind of capacity or lack thereof: for light, for space, even for thought. A building or a street can be aware of itself. Their proximity and geometry in relation to its surroundings, living or otherwise, denote its meaning and its message, while our proximity to theirs reflects our capability and our hubris. More often than not, the urban landscape functions as a vanitas, albeit one we choose to ignore or interpret in any way except the one including death, its most important sign. Here was a place in the time of the new plague that reminded one in every possible way of it, with almost every building bearing its reminders or its intimate associates: cats, pomegranates, the quarantine islands of Lazzaretto Vecchio and Lazzaretto Nuovo, the medico della peste, even its food—fave dei morti is the Venetian version of osso dei morti, the biscuits shaped to resemble the bones of the dead.

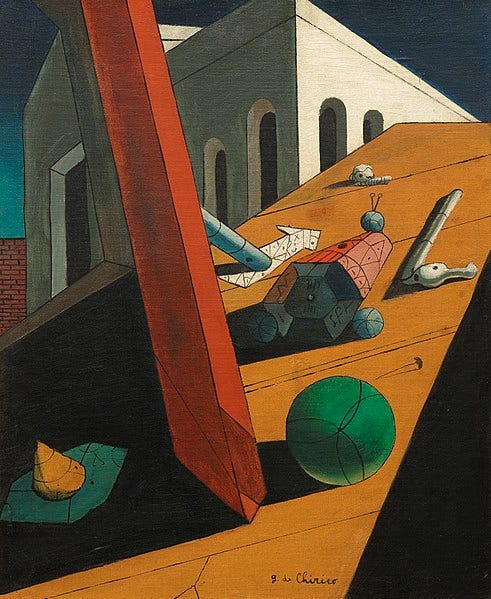

Besides this, another invisible shroud veiled the city. Only a couple of weeks prior, David Graeber, the persistent critic of how we live now and its gross inequalities, had died in Venice. It was impossible not to think of the line in Edith Wharton’s The Custom of the Country, “the slow hot crape-smelling months, lived encircled by shrouded images of woe”. Visible and invisible, Venice permanently and eternally signifies loss. The weight of the vast cloak of mourning we so quickly learned we were wearing that first year acted not just as a mass grieving, but a mass blindness we were unable to adjust to. The elements of living devoid of life—the structures of the day-to-day—were nothing more than skeletons whose bones chimed the hours passing in no discernible direction. In Giorgio de Chirico and the Metaphysical City, Ara H. Merijan writes, apropos the shadowed arches and alien objects in the painting The Evil Genius of a King, that: “the city that hosts them forms a vanitas: a solid object and an emptied sign. And let us remember that it is emptiness—a daemon, a house genie, an absence—that defines architecture to begin with: solidity structured around a hollow. The living city is always already its own skeleton, a tectonic physics haunted by its own vacancy.” We watched our cities, houses, and especially our bodies turn into hollows and hauntings. They were occupied, but with the unease that comes with unfamiliarity, one nestled into the next like a matryoshka, hoping we could reach meaning before nothingness.

Venice is looked at—perhaps more so than other places in the world—but it is also not seen. In this sense, it is like viewing the body, although I would not like to say anything so clichéd about viewing the soul. There is something in Venice beyond the skin of history and its tourist face that is rarely captured, perhaps because it can only be expressed as an impossibility. In a small way, the abstract realisations that come from the peripheries of the unconscious resemble how asthmatics come to know themselves: lost in the concentration of the hissing nebuliser, or in the early dark hours of low breathing when one grasps that the bridge between life and death is as ephemeral as an exhalation. In his 1987 essay “The Objective in Vision”, the photographer Luigi Ghirri referred to “lost landscapes” by saying that: “for this landscape, the only definitions possible are the interchangeable, the indecipherable, the unknowable, the endless, a modern Babel. […] perhaps they are awaiting a new vocabulary, new figures, because the ones we know are worn out, and because many of them have not constituted mere changes in the landscapes much as changes in life.” This ever-shifting Venice is, in the best way, a landscape of ghosts, of spirits released from their static pre-pandemic depths to speak in a language we may only now be capable of understanding. As Eugene Thacker acutely says, “the problem with the world is that one must always speak from within it.” The corollary to this is the world itself can only speak from without; two things forever speaking past each other.

But now, we find ourselves without the very world where we remained cocooned, a metaphysical dilemma that may also be the only circumstance under which we can actually communicate. What this time has done is distort our individual and collective outlooks beyond what most of us could have imagined—excepting fiction and art, which we think of as exercises in the pre-tested tensile imaginary. De Chirico asks, “who can deny the troubling relationship that exists between perspective and metaphysics?”, to which Merjian responds, “it is the absence of subjects that renders these objects more troubling still.” It is not that I consider myself able to more successfully exist in this new time than others—indeed, I have lost even more time within lost time due to periods of near-paralytic anxious despair—but that, having considered myself as breath without body for years by basing my self-regard in the lungs no less than on my cultural and sexual identity, this was how I had already made sense of my place in the world.

As a result of my ability (or disability), part of me understood the strangeness of the landscape even as it recognised the disbelief embedded in our current state of existence. It was because I had seen myself as an object rather than a subject for so long: a nebuliser; an inhaler; a humidifier; a propped pillow; a medicine spoon. Unlike the painter Arcimboldo’s subjects created of objects—fruits, vegetables and flowers—I could not even see myself built into the shape of a person from these things. Instead, I was more like de Chirico’s scattered objects on a remote shadowed plane, searching for a language with which to communicate. It was only now, with the world out of step and out of time, that I began to recognise a subject in those objects, to acknowledge that these distances and shadows always were part of a language that I understood. In Venice I heard and spoke with my lungs as much as with my ears and mouth; I found relief in seeing that, in the city’s signs, it understood my object-self too. In “The Redemption of Objects”, Italo Calvino reflects this in writing:

“The human is the trace that man leaves in things […] it is the continuous dissemination of works and objects and signs […] if we deny this sphere of signs that surrounds us with its thick dust-cloud, man cannot survive. […] every man is man-plus-things […] he recognizes the human that has been in things, the self that has taken shape in things.”

There was never more than a vague shape to our everyday wanderings for, as Manguel says, “getting to know Venice entails losing yourself in it”. We walked at that in-between speed that politely lets fellow pedestrians know you have no destination, but are still aware of them and your surroundings. As if raptured, there were times when people seemingly appeared transported from a parallel dimension in which all was well, at least until one observed details. On their hands and knees, shopkeepers scrubbed pavements outside of their establishments with wooden bristled brushes, soapy water and disinfectant, a quotidian ritual now imbued with extra care; just inside doorways, industrial-size bottles of hand sanitiser, with signs urging and thanking customers to use them generously before moving on, were checked and refilled. At the bases of the innumerable stone pedestrian bridges that connect the city, gondoliers stood, assessing passers-by: spotting tourists with a practised eye, they called out across and above locals, haggling seemingly amongst themselves, a sung-out lowest price drifting over heads in the hope of attracting a customer on the breeze.

At Caffè Florian in St Mark’s Square for a late breakfast one morning, the numerous outside tables that would have been packed at any other time were almost empty. The café persisted, a singer and accompanying musicians in a large bandstand before the columns going through a mostly Sinatra repertoire politely attended by us few. A lone toddler danced energetically, clapping afterwards, to which the ensemble bowed with as much gravity as if the café’s corner of the square had been full. I sipped a cioccolata Casanova—hot chocolate with mint cream—and looked off, in the near distance, at the thin line of tourists waiting to get into the basilica. Squinting, the uniformity of the masks and spacing made them look like they were at a form of devotions; they were, of course. Here and now, regardless of denomination, of belief or disbelief, we all were people of the same small cloth. Those of us not inclined to any of the prayers heard within the walls of St. Mark’s were nevertheless silently asking of the air: why, I wish I had, how long, what if, questions that were muffled in the filters and that became tangled in the weave of our coverings on their way to whatever deities or spirits were still extant and kindly disposed towards our plight.

In front of the cafés that lined the inner streets and corners, ubiquitous white-aproned waiters sung out “Aperol Spritz?” in questioning tones. Thanks to what the New York Times called “an aggressive marketing campaign”, Aperol—the greater cultural importance of which may be as an accessible simulacrum of joie de vivre for our times—is currently the known and accepted drink of the meandering tourist (as opposed to the Bellini of Harry’s Bar and the Gritti Palace, the destination cocktail), and an infinitesimal movement of the head or eye would be sprung upon with more cajoling—sometimes a good quarter-way down the street. Each time I witnessed one or the other, I would remember that breath, for many of Venice’s citizens, is about two kinds of labour, intensifying the complexity of what it meant now to be shut up, vocally and physically. In London, we had a relic of an earlier time still passing through our neighbourhood: a singing knife-grinder, who walked the streets every month or so with sharpening tools on his back, crying out “knives to grind” in a drawn-out call. Once the first lockdown started, we heard him no more, and worried that his voice had been permanently stilled. But sometime in the summer, with the lifting of restrictions, we were relieved to hear him again, same as it ever was, voice ringing in the street.

In a perhaps needlessly stubborn gesture, I would always order Campari soda at these cafés, not out of an attempt to distinguish myself from other tourists, but because a combative amaro—the more medicinal or herbal, the better—gives me a special satisfaction. I once read of a famous editrix and writer, whose name now escapes me, who was known to drink Campari straight. This rather masochistic choice delights me, as it reminds me of being a child in the throes of a week or more-long bout of extreme tightchestedness, not yet able to use an inhaler and having to take an impossibly bitter liquid medicine called Quibron. I would sit up nights with my father, locked in a showdown of three until I forced myself to swallow the small, full-dosage spoon. This direct if slightly perverse road from illness to pleasure does not escape me; I am sure the child who sat obstinately in the cold kitchen thinks of amaro as a reward for taking my medicine back then, but also wants to remind me she has never forgotten our sick times, and neither should I.

Besides Venice’s physical detachment, what contributed most to its unreality at that time was its lack. Its emptiness was a marker of fact that there were fewer tourists than there had been for who knew how long: fifty years or more would not have seemed to me unreasonable. No immense cruise ships loomed in the lagoon; as a result, there was little in the way of water traffic—mostly locals in small boats ferrying supplies, a handful of gondolas in operation. Only the vaporetti continued undeterred, back and forth along their daily stops. The non-Italian voices I heard were almost solely German, it being one of the very few countries having low enough of a dip to consider short leisure travel at the time. I wondered how full it had been at the time when Brodsky was here for Watermark, or if what I was seeing was even less populated than the city he had occupied. It occurred to me that I had never really been to a destination city that was not overflowing with people. Even as a child born in the mid-70s, globalisation—at least in terms of holiday travel—was, if not quite what it had been until recently, still a reminder that the world could go mostly where it pleased, when it pleased them.

There is a great pleasure in being on intimate terms with a city, especially a smaller one. Venice encourages such behaviour from strangers, its layout being so entwined with waterways and passages and bridges no longer than a few steps’ length that, especially at night, it feels as wholly yours as a new lover—to the point where one’s breath quickens in familiar excitement on finding a new bridge; a lively dead-end, full of multicoloured doors whose pigments, softened and blurred by the elements, look like a gallery of Rothkos; a shadowy street where one must be entirely absorbed into its darkness; a park that leads you through its bay and topiary portal to a new and unknown part of the city. It is also the only threesome known to humanity that does not present the problem of how to equitably divide one’s attention: you and your companion are fully engrossed in the revealing yet secretive city.

I wondered just how different Watermark would have been—or would it have been written at all—had Brodsky successfully bedded the possibly Shalimar-perfumed, fur-clad veneziana that he longs for at the beginning of his essay. Had he accurately guessed the perfume, it would be an ideal olfactory profile for the city: its warm, vanillic, citric smokiness is among the few scents that smells the way an animal’s fur feels; luxurious but slightly abrasive, it is easy for me to conjure the image of the gorgeously attired object of his lust prowling the night streets of Venice like a black cat clinging to its fellow shadows. At any rate, his failure is literature’s benefit. His unrequited desire was transferred to Venice, to stones and to water rather than flesh, despite having a kinship, within the tenderness of memory—like Calvino’s city of Zobeide—built to fulfill the uncaptured desire of men’s dreams. It was a passion I understood fully: after a lifetime self-exiling—or escaping—I lived the city as an object of desire, love, or lust—like a person—and to explore it for the first time, and then ever afterwards, is not unlike exploring the body of a lover. To wish to be familiar with every surface, line, curve, and space is an impossibility, for the two constantly change despite retaining a welcoming intimacy through the senses. But one goes back, again and again, to find themselves in what feels like the most private of landscapes. To walk is a form of love; to love is to lose oneself with full faith in the unknown.

Having spent much of one’s childhood sick, there is a great desire to break free of the narrative of illness. This is not to say I deny this thing that I have had for almost as long as I began to recognise my presence in the world, as well as memory, but it is is also like a shadow in that one acknowledges its permanence while also knowing there are blessed times where it can be almost forgotten. Even so, it tugs at the hems of clothes and whispers in the ear when it feels you have been too dismissive of it; it reminds you that, along with your thoughts, it is your life’s companion more than any person could be. I came to Venice to see if there might be a crack in this time that I could escape through, an all-too-human folly.

If one were to anthropomorphise illness, it could be said my breathless shadow was in its element here, where there was respect for its power: the diligent usage of masks, the signs on windows—indossare mascherina and 4 persone per volta—the temperature guns pointed at our foreheads before entering museums. On the vaporetti, the driver-captains would seemingly monitor passengers with eyes in the backs of their heads; they knew when someone had tried to surreptitiously slip one off completely, or just enough. The warnings were loud and stern—enough for the passenger, embarrassed, to apologise and return to full coverage. On the news, there was the story of one who was ejected altogether, deposited on the nearest jetty. Despite the vaporetti being open boats, the Venetians took things fervently. At least then, they could see their past plague reflections too clearly in the waters and mirrors and, again, it was all a relief: validation that the illnesses of breathing were real, and that I had not spent my entire life prisoner to something unreal. Its invisibility had always been its power, and suddenly the world had to accept a presence that did not exist in a way they had been used to understanding. It is also a particular human trait to think, even in illness, that what is worthy of defeating is also expected to manifest as grotesque. And so this unseen sickness is, in every way, John Ruskin’s “fallen human soul” mirroring the truths of the world as it distorts them.

While the overall mood in Venice was cheerful, it could hardly be called celebratory, and it was in one of the city’s narrow passages that I had my reckoning with the unknown observer I had felt was watching me since I first stepped foot on the water’s edge. There was nothing out of the ordinary about the passage itself—another street full of pasticcerie, shops stuffed with Murano glass knickknacks and jewellery, gelaterias with their neat aluminum trays holding small, but seemingly self-replenishing, mountains of pastel-hued gelato which reminded me of my mother’s obi: pistacchio green, crema yellow, fragola pink. It was then I noticed the mask shop. The large window display held very little in the way of the more traditional masks, like the bauta or arlecchino. Instead, it was full of animal masks—rows of foxes, rabbits, more exotic creatures, and fantastical birds, with a single medico della peste off to the side, looking on; not out the window, but at its companions.

It was the orderliness of the display that struck me. Most shops haphazardly displayed theirs, tradition eclipsed by the Commedia the shopper expected to see—the harlequin colours, gilt and ribbon, the eerie glossed porcelain white—knowing full well that new tropes and characters were now projected onto the masks: The Influencer, The Artist, The Politician, The Activist, The Tech Entrepreneur. For all their novelty, they are not without the same echoes of entertainment, courage, villainy, and pathos. Signifiers such as the Commedia masks persist in the same way the tarot does; it is the signified that shifts with time, events, and self-reflection. Arcana, or secrets: greater and lesser, who or what represents our passage through time; the masks we attire ourselves with, in the hope that their addition or removal may reveal new aspects of ourselves, like a shedding of skin. Such signs are everywhere, from the molting of snakes and the rising of the mythic phoenix, to the invisible turnover of our own cells, and the cloak of many furs and the three dresses of sun, moon and stars worn by the fugitive princess in the Grimm’s “Many-Furred Creature”. New skin, new selves; new breath, new life. Even Brodsky came to Venice after being exiled from his old one.

This was less a riot of a menagerie than a judgment gallery: eyeless holes, with no expectation of future merriment, observing the observer, recalling their own previous plague. The darkened sockets did not telegraph a silently felicitous you are here, but a sombre why are you. They were not the beneficent masks of my childhood, with the power to change, but eternal observers of change that they could not alter despite what was projected onto—into—them. My eyes could not meet the place where theirs would have been; in my mind I tried to answer the why that cried and squawked in inquisition. The living and the dead, folly and risk, the desire to either wait for an end or tear through one’s time in the hope that it lets in the next, something better. Perhaps every decision is foolish, because the only unending there can be is the repetition of time that does not include us. Why are you? asked two separate questions—my presence and my existence—neither of which I could have satisfactorily answered. I saw my reflection juxtaposed as if I were the unreal, set against the masks; a Turbeville-esque spectral image, with its implied violence not of the physical, but the linguistic. The images inquire as if the viewer was an intruder.

Whatever the justifications or reasoning, my newly collected metaphors and signs were now like ash in front of that display, with its history of histories: war, disease, and celebration. I had conquered nothing coming here and I knew it—the valedictory belonged to the masks. As the passage came to an end, opening out into a near-empty square, I took a maskless breath. There was still fear of the unknown and disbelief in the world, but there was at least still breath. For now, to see and to breathe was enough, to start to make sense of the senseless. What exists only for a moment can be lived upon in leaner times. In Robert Harbison’s Eccentric Spaces, he speaks of the imaginary Venice of the National Gallery catalogue, where to wander through the paintings is to have an experience in which “uncertainties are richer than the truth, and imaginary Venetian journeys more engaging than the actual. […] but it is also the only way of holding on to the real ones. First the experience imposes itself and then gradually we impose more and more on it, the ordering of learning which falsifies and leaves us feeling how much is left out.” This strange stopped time reimagined and recreated Venice as the imaginary actual, an open-eyed dream-state, the pushing and the pushback of experience and projection resulting in zero; a palpable and present emptiness like breathing, the world as a de Chirico-esque landscape of shadows and masks seeking a subject and meaning.

What was left out was as if it never had been, and what remained—the distance and the space between us that was both our uncertainty and our new language—became truth. Meaning is the search for signs that place us in the world, a shared breath indicating we are not alone, subjects recognising each other in objects, a haruspex diving entrails. Venice sighed while the world slept; counting down to a time in which the very act of breathing would no longer be uncanny, a violence against ourselves and others, or breathlessly restrained. Canaletto’s aquamarine waves lapped at the edge of our collective dream, anticipating that the sleeper might awake, again, to the excitement of possibility. Per sospirare, per respirare. To sigh, to breathe; the unseen wisps that bridge one reality and another, connect us still in a world without touch.

De Chirico, Giorgio. 1914-15. Le mauvais génie d’un roi. Oil on canvas. 61 × 50.2 cm. Museum of Modern Art, New York.

Tomoé Hill’s work has been featured in publications such as Socrates at the Beach, The London Magazine, Vol. 1 Brooklyn, 3:AM Magazine, Music & Literature, Numeró Cinq and Lapsus Lima, as well as the anthologies We’ll Never Have Paris (Repeater Books) and Azimuth (Sonic Art Research Unit at Oxford Brookes University). You can follow her on Twitter @CuriosoTheGreat.