In a short piece titled ‘Protase et Apodose’ (L’Arc, 43, 1970) in which he offers a summary of his purpose, Pierre Klossowski provides the method with a name: a ‘science of stereotypes’. He explains:

‘Let us take the stereotype in its narrowest sense: that is, as any form that ends up being condense in usage, expressing only the licit part of what can be said about a lived fact. Perception, relying as it does on sensual and intellectual habits, is controlled by institutional interpretations—stereotypes, that is—and the lived fact becomes intelligible only if it is cut from its primitive, uncontrollable content. The stereotype thus results from the stratification of the representation emerging out of phantasmal constraint. The harder it is for the representation to come into expression through a word or an image, the more inclined the obsessed subject (be it individual or collective) will be to turn to an already-available stereotype instead. One crucial question is what shall determine the inclination towards one particular stereotype instead of another. In the domain of literary or pictorial communication, the stereotype—the ‘style’—is the residue of a simulacrum that, responding to obsessional pressure, gains currency and falls into common interpretation. As a degraded simulacrum, though, it appears in the guise of an institutional reaction provoked by the echo of a phantasm in both language and esthetic figuration. Here is where the stereotype reveals its function as an occulting interpretation. What does, then, the process of a ‘science of stereotypes’ consist of? It is about stressing—accentuating beyond excess—the stereotype’s character of an obsessional replica of the occulted phantasm. The stereotype thus ends up fulfilling itself the critique of its occulting interpretation.’ (p. 19)

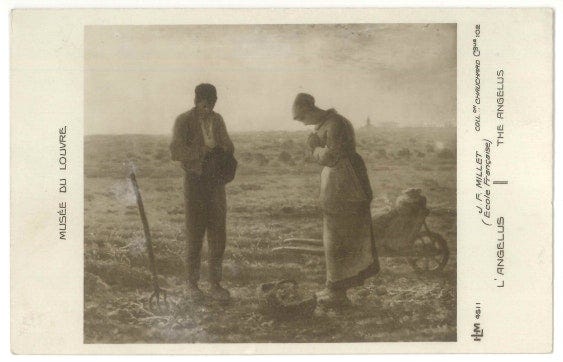

The reader is reminded of Salvador Dali’s paranoiac-critical interpretation of Millet’s L’Angélus—an ‘exploitation’ of the stereotype rather than a science thereof, Klosswoski writes, but which ultimately constitutes an operative method for the task at hand. L’Angélus is endlessly reproduced, replicated, printed and conveyed (like a post, a meme, a tweet, a gif), concealing an obsession that cannot be decoded but through the experimental intensification of its meaning. Dalí sees in L’Angélus the foregrounding of perversion, with the prayer becoming the institutionalised residue of a simulacrum of arousal, depredation and infanticide.

The method certainly works as a vehicle for his own personal obsession. But Dalí explicitly signals the breadth of the sociological phenomenon: L’Angélus as a stereotype of outstanding quantitative reach, printed and reprinted countless times, a global epidemic of replicas and variations, an obsessional control of the communal imagination. And, accordingly, the breadth of the method too: a method for the objectification, verification and communication of the obsession lying within such kinds of ubiquitous, endemic stereotypes (Le mythe tragique de L’Angélus de Millet, 1978). So this is the task at hand now, and it seems that some traits of this standpoint may be at work in the method here developed by Mónica Belevan and Alonso Toledo for their particular blend of esthetic-ethnographic science of stereotypes (Kulturinstinkt, Covidian Æsthetics).

Today, obviously, a science of stereotypes needs to deal with the handheld touchscreen. The act of scrolling up and down and swiping right and left stands as one dominant form in which the lived fact becomes intelligible. Nobody escapes the mundane evidence of the obsessional function of scrolling, of the phantasmal character of the simulacrum embedded on the screen, and of the quantitative proportions of the stereotypes that form the communal imagination.

Patricia Lockwood’s paranoiac-critical exploration of ‘the portal’ offers a case in point for such an inquiry (‘The Communal Mind’, LRB, 41, 2019; No One Is Talking About This, 2021). The portal is where posts, memes, tweets, pics and gifs proliferate. Lockwood the poet clings to it, disintegrates in it, accentuating beyond excess the stereotype’s character as an obsessional replica.

The obsessional content is still obscure; although it is clear that it has to do with the secluded experience of being both mortal and alive, and with the subjection to the seamless act of ‘liking’ and ‘sharing’ that experience, and to see it ‘trending’. Perhaps that is already prefigured in another of Klossowski’s intuitions: that of the continuous expropriation to oneself, and of all others in relation to oneself, in the most advanced state of valuation (La monnaie vivante, 1970).

Furthering a science of stereotypes requires sweeping into the medium proper, though. The portal is not only a space for words and images: it is a technology, and it is a business. A business with its stereotypical cluster of business models and value propositions, of investors and entrepreneurs. A business which determines the inclination towards one particular stereotype instead of another.

Adam Curtis, in his very own paranoiac-critical style, amasses an immense collection of clues about what this business of stereotypes is about (All Watched Over by Machines of Loving Grace, 2011; HyperNormalisation, 2016: Can’t Get You Out of My Head, 2021). The cybernetic phantasm is such that reality—all reality, and not only human reality—amounts to a compound of information and behaviour in which order is achieved through informational and behavioural intercourse (posting, saving, sharing, liking). The phantasm’s revenue model (loss, gain) abides by the same rule (token). And so does its moral model (emoji).

Curtis cuts across the institutional interpretations that keep the phantasm’s obsessional content at bay, offering a narrative that is sometimes political. But some other times the narrative is overtly obsessional, providing the communal imagination with a platform from which the stereotype itself can perhaps fulfil the critique of its occulting interpretation.

Numerous contributions are supplying a potential science of stereotypes with a wealth of materials, now marked by a pandemic that exacerbates the expressions of life in ‘the portal’ and radicalizes the cybernetic phantasm of a world comprised of information and behaviour. The task at hand remains, perhaps, that of intensifying the hunch on the obsession the stereotype stands for.

Postcard of L’Angélus, property of the author.

Fabian Muniesa, an academic in Paris, is the author of The Provoked Economy: Economic Reality and the Performative Turn (Routledge, 2014). Follow him on Twitter @provokedeconomy.